The Talented Patricia Highsmith — and Why Her Stories Work on Film

Not all print-to-film adaptations can preserve the hair-rising chills of a great thriller novel, but three adaptations of work by Patricia Highsmith maintain their creepy splendor, even on celluloid, including Hitchcock’s “Strangers on a Train,” at right.

Kent's Ainsley Moffitt takes a shot against the Millbrook goalie.Photo by Lans Christensen

Kent's Ainsley Moffitt takes a shot against the Millbrook goalie.Photo by Lans Christensen Lily Kennedy on attack for Millbrook.Photo by Lans Christensen.

Lily Kennedy on attack for Millbrook.Photo by Lans Christensen. Ainsley Moffitt celebrates after scoring a goal for Kent.Photo by Lans Christensen

Ainsley Moffitt celebrates after scoring a goal for Kent.Photo by Lans Christensen

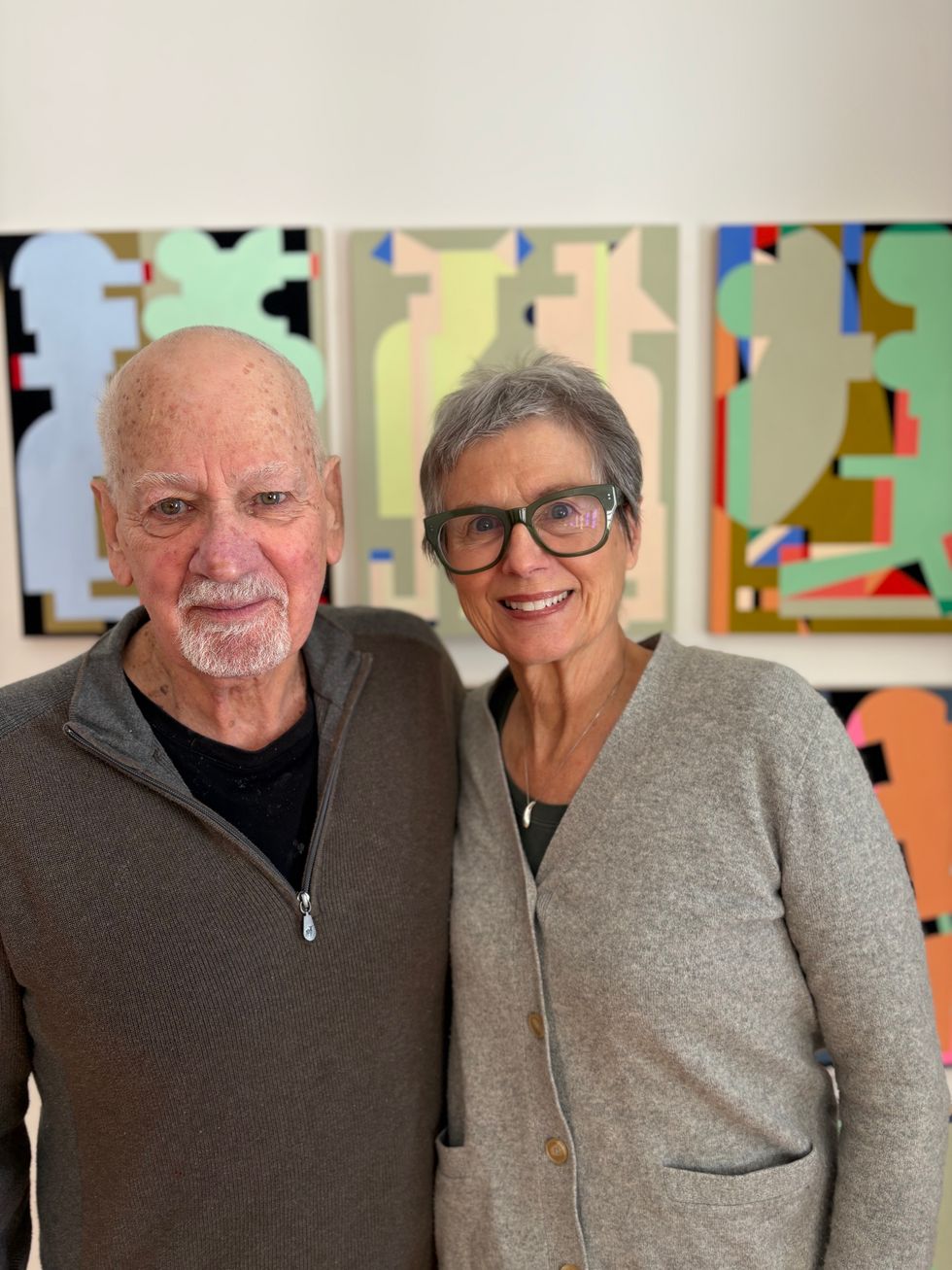

Plagens and Fendrich at home in front of some of Fendrich’s paintings. Natalia Zukerman

Plagens and Fendrich at home in front of some of Fendrich’s paintings. Natalia Zukerman