Latest News

Cornwall honors former slave and war hero

Feb 10, 2026

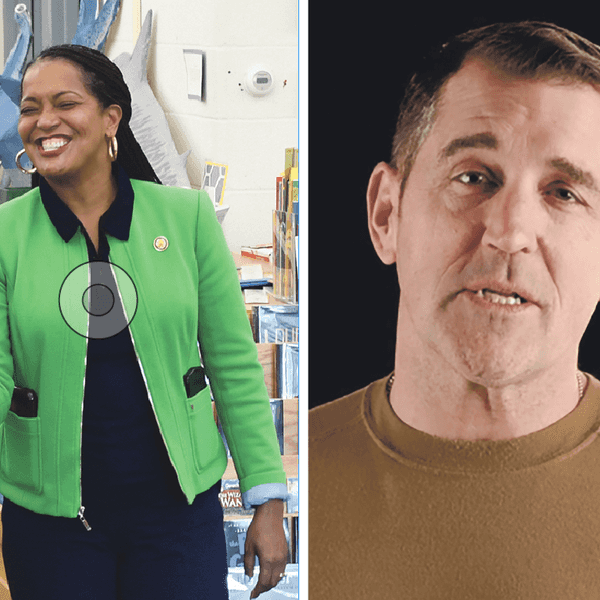

First Selectman Gordon Ridgway presents the proclamation declaring Feb. 8 Robin Starr Day in Cornwall.

Riley Klein

CORNWALL — Nearly 245 years a er he purchased his freedom, Robin Starr — a formerly enslaved Revolutionary War veteran— was officially recognized last week when the Town of Cornwall proclaimed Feb. 8 as Robin Starr Day.

Starr, who served in the Revolutionary War, is the subject of a research project undertaken by the7th-grade class of Cornwall Consolidated School. He was a veteran of many battles, including the Battle of Stony Point and the Battle of Yorktown, and he was a recipient of the Badge of Military Merit (an early version of the Purple Heart).

Pippa Cavalier, a 7th grader at CCS, explained Starr earned the medal “for being wounded twice in battle. And he was also the first Black soldier to get that award. ”On Feb. 8, 1781, Starr became a free man by purchasing his freedom. He later owned land in Cornwall and Sharon, as verified by census data and meeting minutes discovered through student research in conjunction with the Cornwall Historical Society.

Nearly 245 years later, First Selectman Gordon Ridgway prepared a proclamation declaring Feb. 8, 2026, as Robin Starr Day. The proclamation was presented to the 7th graders on Feb. 5. As part of the 250th anniversary of the Revolution, Cornwall was compiling a list of local veterans. Starr was not previously on the list, but because of the student research he has since been added.

“You’ve led us to learn a lot about this story,” Ridgway said to the class, praising the efforts of the students.

The idea to research Starr came when the students spoke with John Mills, president of the Alex Breanne Corporation in West Hartford, whose company researches formerly enslaved peoples and brings their stories to light.

“The timing of this worked well,” said Will Vincent, history teacher at CCS. He pointed out that Starr’s Feb. 8 payment to buy his freedom coincides with Black History Month. “It all ties together.”

A presentation on Starr’s life and legacy will be given by the students at Troutbeck Symposium this spring. There, they will show informational posters about Starr’s life, a three-dimensional model of his land near the Housatonic River, a depiction of the uniform he likely wore serving in the 2nd and 7th Regiments, his family tree and other visual cues to bring his story to life.

Cavalier noted that Starr does not have a gravestone in town, but some of his descendants are buried in Calhoun Cemetery. “So, we decided to get him an honorary gravestone in Calhoun Cemetery.”

The students plan to deliver a full address to the community at the Memorial Day ceremony in May.

Keep ReadingShow less

Kaelan Mullen-Leathem jumps in the Salisbury Invitational.

Patrick L. Sullivan

SALISBURY — Salisbury Winter Sports Association kicked off its centennial celebration Friday evening, Feb. 6, in classic festive style as temperate weather – alongside roaring bonfires and ample libations – kept Jumpfest-goers comfy as skiers flew, fireworks boomed and human dog sledders, well, did what human dog sledders do.

Before the truly hyperborean conditions of Saturday and Sunday set in, Friday night brought the crowds – enough that both the vast SWSA parking lot, and overflow, were completely full by 6:45 p.m.

SWSA President Ken Barker, found just after descending the steep, slick landing of the K65 jump in his characteristic crampons, said “this night is for the community and people turned out.”

Target jumping launched just after 7 p.m. as skiers sought to hit a 65- meter and 70-meter distance – about 213 and 230 feet, respectively. For the 70-meter launch, Jack Kroll of Lake Placid, New York’s NYSEF team and Spencer Jones of Brattleboro, Vermont’s HHN outfit tied with 69-meter jumps and $500 on the line.

Light snow started to fall as fireworks launched from the top of Satre Hill, with SWSA’s red, blue and white colors illuminating the healthy snowpack below as watchers “oohed” and “aahed,” swilling specialty beers from Norbrook Farm Brewery, including an IPA brewed specifically for the event.

Wrapping up the evening was the always-anticipated human dog sled race, with spectators cheering, laughing and occasionally grimacing as teams of six – one sledder and five pullers – sprinted and sometimes sprawled across the icy flats below the K65 landing. The Terrible Toymakers ended up claiming the coveted victory, making quick work of the course with the evening’s fastest time of 21.19 seconds.

Saturday morning was met with single-digit temperatures and piercing wind. But that didn’t stop the youth jumpers from skiing down the K20 and K36 hills.

It was the first official launch of the new jump on the K36 hill. Spencer Jones caught big air in the youth competition and soared 35.5 meters, the longest jump of the morning.

Guests entering Satre Hill were greeted by cutouts of ski jumpers who competed there over the past 100 years. Spectators huddled around the bonfires situated on either side of the landing zone. Mac-n-cheese provided warmth to some, while others went for hot toddies. And the SWSA snack bar was serving up burgers, hot dogs and brats.

Rocco Botto, a Cornwall selectman, was in attendance and said it was his first time at Jumpfest. He wisely wore four layers of clothing to combat the cold.

Between events, some young spectators kept occupied by building an igloo. Before the roof of the structure could be built, it was announced that jumping for the rest of the day was postponed due to high wind. It was deemed unsafe for jumpers.

The Nordic combined competition took place Saturday afternoon, which combines ski jumping and cross-country skiing into a single winter sports event.

Sunday morning remained in the single digits, but the wind wasn’t as strong as Saturday. With the sunshine it was almost comfortable. A small but dedicated crowd of about 150 was on hand around 10 a.m. when the Salisbury Invitational event got underway with trial jumps.

One jumper was SWSA’s own Ariel Picton Kobayashi, author of “Ski Jumping in the Northeast: Small Towns and Big Dreams.” Islay Shiel, a junior at Housatonic Valley Regional High School representing SWSA in the competitions, placed second among females on the K65 hill. The winner was her Junior Nationals teammate Caroline Chor, who jumps for Ford Sayre. The duo won gold together at the Junior National Ski Jumping competition in Utah in 2025.

Keep ReadingShow less

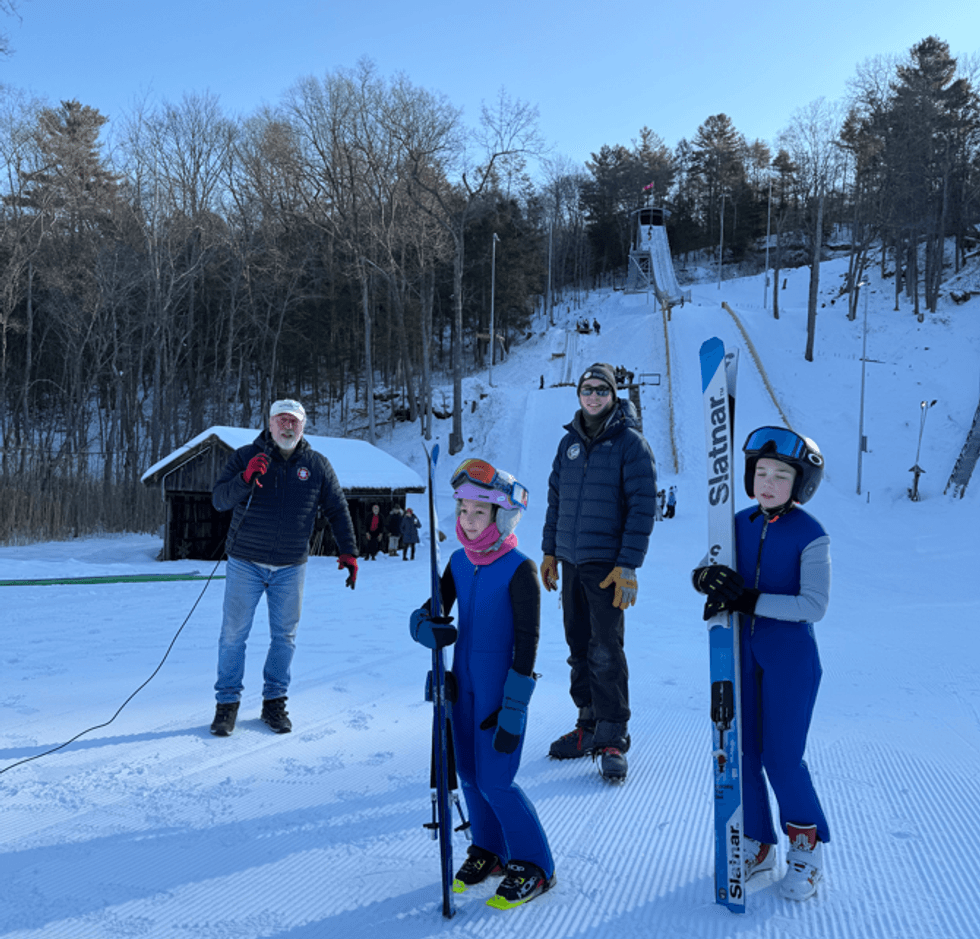

Gus Tripler prepares to jump from the new 36-meter jump.

Margaret Banker

SALISBURY - With the Winter Olympics just weeks away, Olympic dreams felt a little closer to home for Salisbury Central School students on Feb. 4, when student ski jumpers from the Salisbury Winter Sports Association put on a live demonstration at the Satre Hill Ski Jumping Complex for more than 300 classmates and teachers.

With screams of delight, student-athletes soared through the air, showcasing years of training and focus for an audience of their peers. The atmosphere was electric as the jumpers soaked up the attention like local celebrities.

Satre Hill and SWSA are celebrating their 100th Anniversary of ski jumping in northwest Connecticut this week. As part of this week’s festivities, Salisbury Central School was invited to watch a demonstration of jumping on the 20-meter and the newly installed 36-meter ski jumps.

The event began with Coach Seth Gardner welcoming Salisbury Central School to the jump complex and explaining the sport and training that goes into ski jumping.

Ski jumpers Oona Mascavage and Camden Hubbard assisted Coach Gardner by showing off equipment used in the sport from the oversized skis to the aerodynamic jump suits as well as the proper starting form known as the in-run position.

Then, Willie Hallihan of the SWSA offered students a brief history of ski jumping in Salisbury, tracing the sport’s local roots back a century to when the Satre brothers first launched themselves off a barn before going on to construct the area’s first ski jumping hill. After the history lesson, younger jumpers showed how to begin the sport by skiing down the landing portion of the hill called the outrun.

Jumpers proceeded to show basic jumping from the 20-meter hill, where most beginners start. The event was capped with a demonstration of jumping from the bigger 36-meter hill, where the real flying begins led by one of SWSA's veterans, Gus Tripler.

The SWSA operates one of the oldest ski jumping facilities in the United States and is the home club of 1956 Olympic ski jumper Roy Sherwood and legendary ski jumping coach Larry Stone. The organization has hosted Olympic ski jumpers over the years, including many members of the current U.S. Olympic ski jumping team, now competing in Italy at the Winter Games.

The future of ski jumping at SWSA remains strong, with plans underway to install artificial grass that would allow for summer jumping and year-round training. Islay Sheil, a homegrown jumper, is currently competing on the Junior National Ski Jumping circuit, which includes Olympic-size 100-meter hills.

The 100th anniversary celebrations will continue Feb. 6–8 with Jumpfest, which will feature ski jumping events at Satre Hill in Salisbury.

Keep ReadingShow less

Classifieds - February 5, 2026

Feb 04, 2026

Help Wanted

PART-TIME CARE-GIVER NEEDED: possibly LIVE-IN. Bright private STUDIO on 10 acres. Queen Bed, En-Suite Bathroom, Kitchenette & Garage. SHARON 407-620-7777.

The Scoville Memorial Library: is seeking an experienced Development Coordinator to provide high-level support for our fundraising initiatives on a contract basis. This contractor will play a critical role in donor stewardship, database management, and the execution of seasonal appeals and events. The role is ideal for someone who is deeply connected to the local community and skilled at building authentic relationships that lead to meaningful support. For a full description of the role and to submit a letter of interest and resume, contact Library Director Karin Goodell, kgoodell@scovillelibrary.org.

Weatogue Stables in Salisbury, CT: has an opening for experienced barn help for Mondays and Tuesdays. More hours available if desired. Reliable and experienced please! All daily aspects of farm care- feeding, grooming, turnout/in, stall/barn/pasture cleaning. Possible housing available for a full-time applicant. Lovely facility, great staff and horses! Contact Bobbi at 860-307-8531. Text best for prompt reply.

Services Offered

COLBYS TREE SERVICES: provides reliable tree removal, trimming, and storm cleanup. Locally owned and fully insured, we’re committed to safe work, honest service, and keeping your property looking its best. CALL/TEXT 860-248-9456.

Hector Pacay Landscaping and Construction LLC: Fully insured. Renovation, decking, painting; interior exterior, mowing lawn, garden, stone wall, patio, tree work, clean gutters, mowing fields. 845-636-3212.

PROFESSIONAL HOUSEKEEPING & HOUSE SITTING: Experienced, dependable, and respectful of your home. Excellent references. Reasonable prices. Flexible scheduling available. Residential/ commercial. Call/Text: 860-318-5385. Ana Mazo.

Real Estate

PUBLISHER’S NOTICE: Equal Housing Opportunity. All real estate advertised in this newspaper is subject to the Federal Fair Housing Act of 1966 revised March 12, 1989 which makes it illegal to advertise any preference, limitation, or discrimination based on race, color religion, sex, handicap or familial status or national origin or intention to make any such preference, limitation or discrimination. All residential property advertised in the State of Connecticut General Statutes 46a-64c which prohibit the making, printing or publishing or causing to be made, printed or published any notice, statement or advertisement with respect to the sale or:rental of a dwelling that indicates any preference, limitation or discrimination based on race, creed, color, national origin, ancestry, sex, marital status, age, lawful source of income, familial status, physical or mental disability or an intention to make any such preference, limitation or discrimination.

Houses For Rent

3 BR/1 BA: fully furnished/fully equipped raised ranch style home in Canaan, available February 1 to June 30. Great opportunity to experience the area! $2600/month. 860-671-8753 or contact Elyse Harney Real Estate.

Keep ReadingShow less

loading