Katie Worth, “Miseducation: How Climate Change is Taught in America”

New York: Columbia Global Reports, 2021

You don’t have to believe in gravity, or that the Earth is round, or that smoking tobacco will give you cancer, or that inhaling asbestos will poison your lungs. You should, but you don’t have to. It’s a free country. You don’t have to believe in evolution, either. But you should. It’s science.

Science.

Those who choose not to believe science can find radio frequencies, television channels and websites chockful of crazytalk. Yet 270 million cases of COVID-19 have been confirmed worldwide. That’s right, 270 million. More than 5 million people have died from it, including now almost one million Americans, more than 30,000 just last month. (www.coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html) Science tells us that. And a tough winter is coming. Science tells us that, too. But, some people say, the pandemic is over. Some people will tell you COVID doesn’t exist at all.

Facts about our global pandemic to one side, no truth is more urgent and existential for us to share as the warming of our planet. Originally from Chico, a part of California that’s been consumed by raging wildfires in recent years, journalist Katie Worth is an investigative journalist associated with the signature public broadcasting’s series “Frontline.” She has spent a lot of time with science — and scientists.

They tell her that if we do not slow down the pace of global warming, floods eventually will swamp our coastal habitats and turn many of our forests into ash. You can’t see or smell COVID, and you can’t see climate change that easily either. But today, she writes, if you look for an authoritative scientific study that says humans are not warming the climate, that’s like “searching for an earthworm in a henhouse.” “The evidence for human-caused climate change,” she notes, is “as strong as the evidence linking cigarettes and cancer.”

Worth has spent a lot of time lately with teachers. She assembled a research team and a database of 50 state K-12 education policies. She analyzed 50 state education standards, reviewed scores of textbooks; screened educational films and videos; pored over thousands of articles and pamphlets and brochures; interviewed teachers, authors, editors, and publishers; and traveled to more than a dozen communities to look at teaching and learning in action. The result is a jaw-dropping book that every teacher and parent ought to read.

“If today is a school day in America,” Worth reminds us, “approximately 3 million teachers are educating 50 million children enrolled in 100,000 public schools right now.” But the teaching materials, textbooks, and lesson plans they use to educate our children — and many of the state education requirements they are obliged to follow — are infested with false information. This is not a new phenomenon. K-12 education often used to downplay evolution or the horrors of slavery or the murderous ways we cleared our continent of Native Americans. “Miseducation” shows how the topic that’s being suppressed and suppressed systematically today is climate change.

The problem is related to an opportunity. There are, as Worth puts it, trillions of dollars of money still left in the ground — in coal, oil, natural gas — and the industries that specialize in its extraction stand to make a lot of money mining and drilling for it and turning it into energy. This in itself is not a bad thing. Money and making it are keys to survival. But when business interests can’t coexist with truths about the effects of industry on health and society, that’s a problem.

And when these same business interests fund politicians, and politicians then support these interests, then we have liars in power. Lies are not new to politics, either. But going the wrong way on climate change will be fatal.

“Miseducation” shows how our giant fossil fuel companies — ExxonMobil, Chevron, ConocoPhillips (Eversource is in here, too) — have directly sponsored, with billions of dollars, suites of films and booklets and pamphlets, free curricular materials, field trips, prizes and scholarships all to stop, remove, or water down lessons about the damage we do to our world with our careless policies about energy. Cartoon figures like Charlie Carbon Monoxide and Harry Hydrocarbon pop into the teaching materials they distributed by the million.

The American Petroleum Institute and Dupont teamed up to train oil workers to fan out into American classrooms and give show-and-tell presentations on “The Magic Barrel.” Exxon got Disney and Mickey and Goofy involved. One company created an activity booklet with little puzzles and games called “Natural Gas: Your Invisible Friend.” American publishing companies routinely let state review boards in oil-rich Texas — our country’s largest state purchaser of textbooks — and elsewhere dilute the science in the readings we give our kids.

“Miseducation,” short as it is, is a worthy successor volume to Erik M. Conway and Naomi Oreskes’s Merchants of Doubt, Jane Mayer’s Dark Money, and Nancy MacLean’s Democracy in Chains. But in many ways, because it focuses on how we educate children, it’s attuned to more subtleties in the ways nefarious forces can shape how Americans think.

“Teaching climate change as a debate is as damaging as outright denial,” Worth tells. There are many takeaways for teachers here about the perils of both-sidesism. And for others who talk to children, including religious leaders and the media.

Focused on what we can do to improve teaching and learning, Worth points to robust and factual information resources like www.cleanet.org and www.ncse.ngo. She implores us to incorporate climate discussion not only into biology, chemistry and physics standards, but in arts, language, history, civics and economics.

In a book full of quotations and excerpts and interviews citing the misinformation circulating in our schools, she calls for educational resources that match and counter the false and sometimes sophisticated apparatus of graphs, charts, and footnotes in fossil fuel industry propaganda.

All of our ideas come from somewhere. It’s the story of how knowledge is shared and taught and socialized. If that’s of interest to you, get a copy of this masterpiece.

“Miseducation” is published by Columbia Global Reports (www.globalreports.columbia.edu/about/donors/) with the support of the PBS series “Frontline” (www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/about-us/our-funders/) and an investigative reporting initiative called the Ground Truth Project (www.thegroundtruthproject.org/about/supporters/).

Peter B. Kaufman lives in Lakeville and works at MIT. He is the author of “The New Enlightenment and the Fight to Free Knowledge.”

Kent's Ainsley Moffitt takes a shot against the Millbrook goalie.Photo by Lans Christensen

Kent's Ainsley Moffitt takes a shot against the Millbrook goalie.Photo by Lans Christensen Lily Kennedy on attack for Millbrook.Photo by Lans Christensen.

Lily Kennedy on attack for Millbrook.Photo by Lans Christensen. Ainsley Moffitt celebrates after scoring a goal for Kent.Photo by Lans Christensen

Ainsley Moffitt celebrates after scoring a goal for Kent.Photo by Lans Christensen

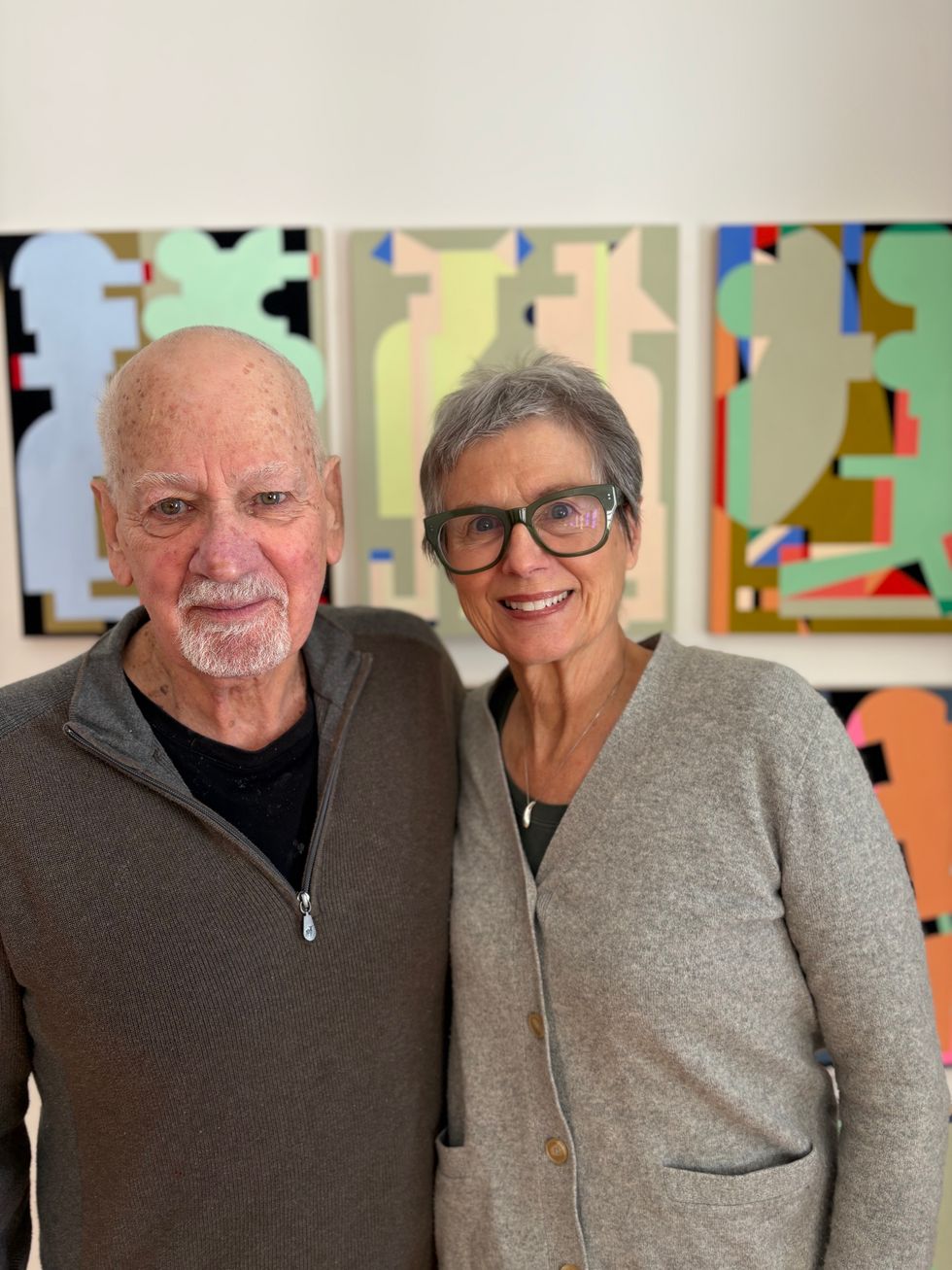

Plagens and Fendrich at home in front of some of Fendrich’s paintings. Natalia Zukerman

Plagens and Fendrich at home in front of some of Fendrich’s paintings. Natalia Zukerman

Climate change: understanding reality takes some effort