Latest News

Classifies - November 13, 2025

Nov 12, 2025

Help Wanted

CARE GIVER NEEDED:Part Time. Sharon. 407-620-7777.

Weatogue Stables has an opening: for a full time team member. Experienced and reliable please! Must be available weekends. Housing a possibility for the right candidate. Contact Bobbi at 860-307-8531.

Services Offered

Deluxe Professional Housecleaning: Experience the peace of a flawlessly maintained home. For premium, detail-oriented cleaning, call Dilma Kaufman at 860-491-4622. Excellent references. Discreet, meticulous, trustworthy, and reliable. 20 years of experience cleaning high-end homes.

Local editor with 30 years experience offering professional services: to writers working on a memoir or novel, or looking for help to self publish. Hourly rates. Call 917-331 2201.

SNOW PLOWING: Be Ready! Local. Sharon/Millerton/Lakeville area. Call 518-567-8277.

Hector Pacay Service: House Remodeling, Landscaping, Lawn mowing, Garden mulch, Painting, Gutters, Pruning, Stump Grinding, Chipping, Tree work, Brush removal, Fence, Patio, Carpenter/decks, Masonry. Spring and Fall Cleanup. Commercial & Residential. Fully insured. 845-636-3212.

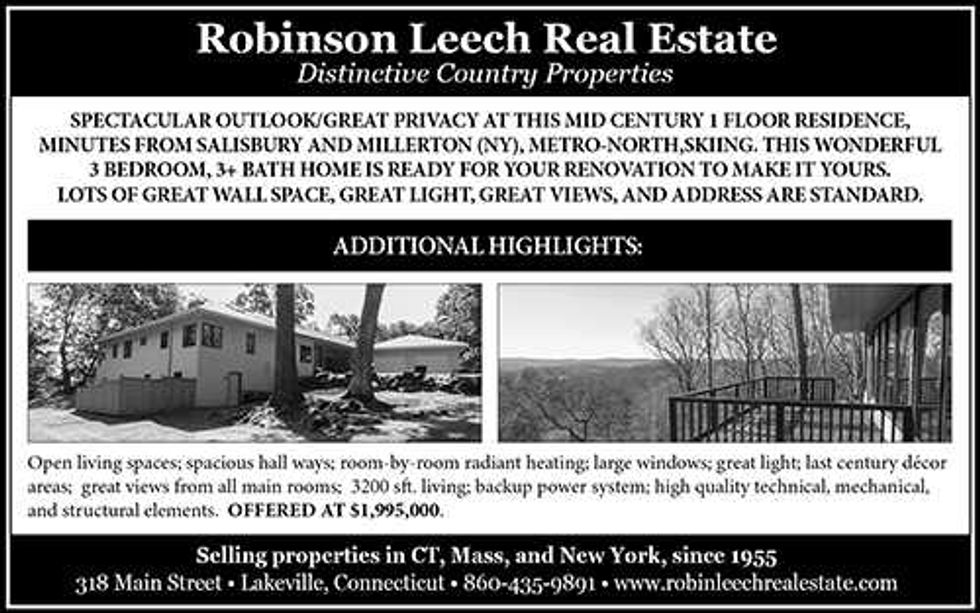

Real Estate

PUBLISHER’S NOTICE: Equal Housing Opportunity. All real estate advertised in this newspaper is subject to the Federal Fair Housing Act of 1966 revised March 12, 1989 which makes it illegal to advertise any preference, limitation, or discrimination based on race, color religion, sex, handicap or familial status or national origin or intention to make any such preference, limitation or discrimination. All residential property advertised in the State of Connecticut General Statutes 46a-64c which prohibit the making, printing or publishing or causing to be made, printed or published any notice, statement or advertisement with respect to the sale or rental of a dwelling that indicates any preference, limitation or discrimination based on race, creed, color, national origin, ancestry, sex, marital status, age, lawful source of income, familial status, physical or mental disability or an intention to make any such preference, limitation or discrimination.

Sharon, 2 Bd/ /2bth 1900 sqft home: on private Estate-Gbg, Water, Mow/plow included. utilities addtl. Please call: 860-309-4482.

Retired gentleman looking: for a piece of hunting property in Lakeville. 10 acres or more. Very responsible. Safety first.

Keep ReadingShow less

Recount confirms Bunce as new First Selectman

Recount confirms Bunce as new First Selectman

NORTH CANAAN — A recount held Monday, Nov. 10, at Town Hall confirmed Democrat Jesse Bunce’s narrow victory over incumbent First Selectman Brian Ohler (R) in one of the tightest races in town history.

“A difference of two votes,” said recount moderator Rosemary Keilty after completing the recanvass, which finalized the tally at 572 votes for Bunce and 570 for Ohler.

“It’s overwhelming,” said Bunce after the result. To the poll workers he said, “Thank you everyone for your hard work. It’s been an honor.” And he thanked Ohler for his service to the town.

The two men shook hands.

“Congratulations,” said Ohler. “Wish you all the best. When you succeed, the Town of North Canaan succeeds and that’s why we’re all here.”

Ohler will continue on the board as a selectman. Newcomer Melissa Pinardi (R) will fill the third seat on the board.

The recount was required by state law after the initial count on Election Day showed a difference of three votes (572 to 569).

Ohler gained one vote in the recount and Bunce’s total was unchanged. Keilty said the extra vote was likely from a ballot that the tabulator did not read properly last Tuesday.

There was a single ballot that was not counted because the voter selected both Ohler and Bunce for first selectman.

Looking ahead to the coming term, Bunce said he was ready to get to work. “We have a good game strategy of how we’d like to handle the first 90 days and I look forward to executing that,” he said. “I think we can do lots of fun, exciting things for the town that’ll benefit all sorts of people.”

In a follow up statement, Ohler wrote, “The future of North Canaan is bright.” He continued, “Now is not the time to wish failure or misstep upon any elected official. We will all serve each other and our town, just as your votes intended them to do. It has been an immense honor to serve as your First Selectman... We are North Canaan.”

The first meeting of the new Board of Selectmen will be held in Town Hall Monday, Dec. 1, at 7 p.m.

Keep ReadingShow less

photo by ruth epstein

Brent Kallstrom, commander of Hall-Jennings American Legion Post 153 in Kent, gives a Veterans Day message. To the left is First Selectman Martin Lindenmayer, and to the right the Rev. John Heeckt of the Kent Congregational Church.

KENT – The cold temperatures and biting winds didn’t deter a crowd from gathering for the annual Veterans Day ceremony Tuesday morning, Nov. 11.

Standing in front of the memorials honoring local residents who served in the military, First Selectman Martin Lindenmayer, himself a veteran, said the day is “not only a time to remember history, but to recognize the people among us—neighbors, friends and family—who have served with courage, sacrifice and devotion. Whether they stood guard in distant lands or supported their comrades from home, their service has preserved the freedoms we enjoy each day.”

While veterans live by the words duty, honor, country, said Lindenmayer, it doesn’t mean they are warmongers. “The soldier, above all, prays for peace.” He told the veterans the town is proud of them. “We pledge to honor your service not only with words, but with our actions—by building a community and a country worthy of your sacrifice.”

Brent Kallstrom, commander of Hall-Jennings American Legion Post 153, gave a message from the American Legion in which he said Veterans Day can be traced to the armistice that ended World War I.

“For many veterans, our nation was important enough to endure long separations from their families, miss the births of their children, freeze in sub-zero temperatures, bake in wild jungles, lose limbs and far too often, lose their lives,” he said.

He noted that fewer than 10% of Americans can claim the title veteran and less than one half of 1% of the population currently serves.

“Veterans have given us freedom, security and the greatest nation on earth,” said Kallstrom. “It is impossible to put a price on that.”

Local veterans shot three rounds and bagpiper Don Hicks provided music. The Rev. John Heeckt of the Kent Congregational Church gave the invocation and the Rev. Richard Clark of St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church gave a concluding prayer.

Members of St. Andrew’s then hosted a luncheon for all veterans and their families.

Keep ReadingShow less

Ava Segalla, Housatonic Valley Regional High School's all-time leading goal scorer, has takes a shot against Coventry in the Class S girls soccer tournament quarterfinal game Friday, Nov. 7.

Photo by Riley Klein

FALLS VILLAGE — Housatonic Valley Regional High School’s girls soccer team is headed to the semifinals of the state tournament.

The Mountaineers are the highest seeded team of the four schools remaining in the Connecticut Interscholastic Athletic Conference Class S playoff bracket.

HVRHS (3) will play Morgan High School (10) in the semifinals. On the other side of the bracket, Canton High School (4) will play Old Saybrook High School (9). The winners of both games will meet in the Class S championship game.

To start the tournament, HVRHS earned a first-round bye and then had home-field advantage for the second-round and quarterfinal games.

In the second round Tuesday, Nov. 4, HVRHS won 4-3 against Stafford High School (19) in overtime. Ava Segalla scored three goals for Housatonic, including the overtime winner, and Lyla Diorio scored once. Bella Coporale scored twice for Stafford and Gabrielle Fuller scored once.

HVRHS matched up against Coventry High School (11) in the quarterfinal round Friday, Nov. 7. In the 2024 tournament, Coventry eliminated the Mountaineers in the second round.

Revenge was served in 2025 with a 4-2 win for HVRHS. Segalla scored her second hat trick of the tournament and Georgie Clayton scored once. Coventry’s goals came from Jianna Foran and Savannah Blood.

“The vibes are great,” said HVRHS Principal Ian Strever at the quarterfinal game.

The semifinal against Morgan will be played Wednesday, Nov. 12, on neutral ground at Newtown High School.

If HVRHS wins, it will mark the girls soccer team’s first appearance in the Class S title game since 2014.

Morgan was the runner-up in last year’s Class S girls soccer tournament, losing in penalty kicks to Coginchaug High School.

Keep ReadingShow less

loading