Latest News

Filmmaker Oren Rudavsky

Provided

“I’m not a great activist,” said filmmaker Oren Rudavsky, humbly. “I do my work in my own quiet way, and I hope that it speaks to people.”

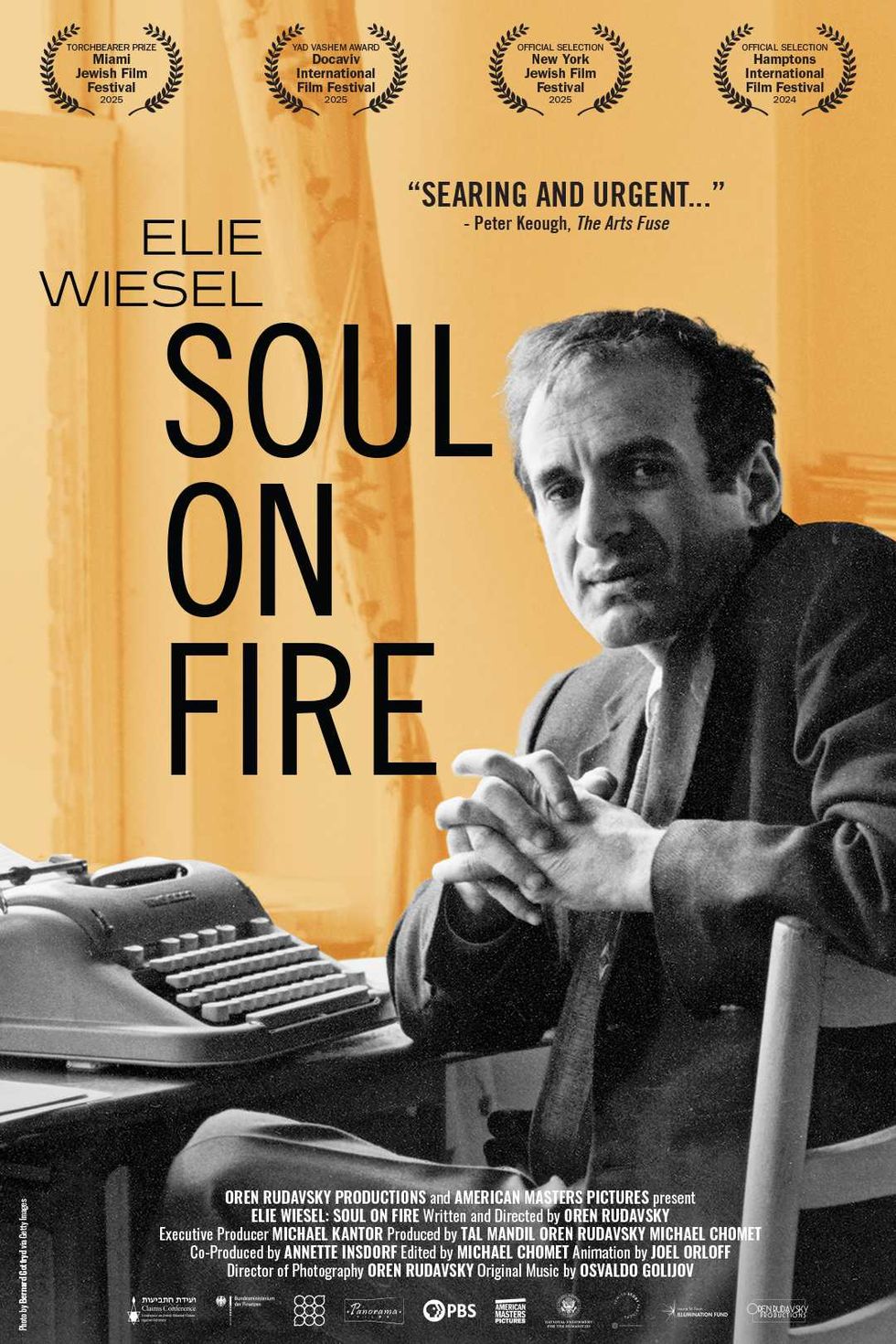

Rudavsky’s film “Elie Wiesel: Soul on Fire,” screens at The Moviehouse in Millerton on Saturday, Jan. 18, followed by a post-film conversation with Rudavsky and moderator Ileene Smith.

Rudavsky, who lives in New York City and has a home in Lakeville, has been screening films at The Moviehouse for nearly three decades. “I was the first independent filmmaker to show a film there back in 1997 or ’98,” he recalled, with “A Life Apart: Hasidism in America.” “I think I’ve shown four or five films there over the years.”

Best known for his searing 1958 memoir, “Night,” Elie Wiesel forever altered how the Holocaust would be written about and remembered. A teenage survivor of Auschwitz and Buchenwald, the Romanian-born author became an international spokesperson for memory, conscience and moral responsibility. Yet Rudavsky’s documentary looks beyond Wiesel’s public role, revealing a man who was, in the director’s words, “intensely private and profoundly public.”

Rudavsky’s connection to Wiesel is also personal. “I grew up in Boston,” he said, “and Elie started teaching there in ’77 or ’78, and my mother took a class with him.” His father was a Reform rabbi, and the family’s shelves were filled with Jewish books, including Wiesel’s, such as “Night,” “Jews of Silence,” and the volume that would later lend its name to the film: “Souls on Fire.”

“His mystical storytelling is where he’s at his best,” Rudavsky said of the book. “So eloquent and beautiful — you could pick up any page and be transported into this other world, this other realm. ‘Night’ does that too, in a horrifying way, but it achieves that same sort of consciousness change.”

Wiesel, who died in 2016 at the age of 87, would go on to establish what is now the Elie Wiesel Center for Jewish Studies at Boston University, an institution devoted to ethical inquiry, dialogue and human rights, principles that shaped both his teaching and his writing.

“One of the things that is most striking to me in living with Elie Wiesel’s work for the past four years,” said Rudavsky, “is how civilized, cultured, eloquent, soft-spoken and gentle a person he was, how loving in general a person he was.” That gentleness and quiet insistence on civility becomes one of the film’s most moving revelations.

The documentary does not present Wiesel as a saint or a monument. It lingers instead on the human questions. “How do you overcome trauma?” Rudavsky asked. “How do you live with it? Do you ever overcome it? I don’t think Elie did overcome it, but I think he learned to live with it and learned to enjoy life — sleeplessly perhaps — but he enjoyed the world.”

To evoke the inner life of memory, the film incorporates hand-painted animation by Joel Orloff, inspired in part by the illustrator Mark Podwal, who collaborated with Wiesel on several projects. “A few of the animations are inspired by his brilliant work,” Rudavsky said. “Everything else is from Joel Orloff’s imagination.”

The technique they employed in the film was influenced by South African artist William Kentridge, whose charcoal drawings evolve through erasure and reworking. “We wanted to evoke memory through the animation,” Rudavsky explained. “Joel painted on glass, smudged it, poured water onto it.” The result is a haunting, fluid visual language, neither literal nor ornamental.

“At first, I wasn’t sure I was going to use animation,” Rudavsky explained. “But when I read portions of Elie’s autobiography, he intersperses these dreams about his family, his father, and I thought, ‘This just cries out for animation.’” The effect is striking: a fusion of conscious and subconscious, past and present.

Marion Wiesel, Elie’s wife, translator, and closest collaborator, passed away in February of last year. She was able to see the film at a screening at Lincoln Center. “She said to me, ‘I love the film, but it caused me pain because it made me fall in love with Elie all over again,’” Rudavsky recalled. “Which was heartbreaking — but for a filmmaker, what more can you really ask for?”

Marion, he added, was a remarkable figure in her own right, deeply involved in civil rights activism. A member of the NAACP in the 1950s, she encouraged Elie to look beyond the Jewish world he mostly traveled in and toward a broader global perspective.

That outward gaze was central to Wiesel’s public life. The film revisits moments when he spoke directly to political power, including his famous confrontation with President Ronald Reagan over a planned visit to a cemetery in Bitburg, Germany, where SS members were buried. “Elie lost the battle but won the war,” Rudavsky said. “Because how he spoke up was much more lasting than whatever Reagan did.” He adds that what mattered most was the tone: “It was a civil dialogue. A gentle dialogue.”

Moderating the post-screening discussion will be Ileene Smith, editor at large for Farrar, Straus and Giroux and editorial director of Jewish Lives, the prizewinning biography series published by Yale University Press. Smith worked closely with both Elie and Marion Wiesel on many books, including the new translation of “Night.” In 1986, she accompanied the Wiesels to Oslo when Elie received the Nobel Peace Prize. Her husband, Howard Sobel, served for many years on the board of the Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity.

Wiesel believed that memory was not passive; it was a moral act. Asked about the moral obligation to bear witness, Rudavsky said, “It’s an endless moral obligation. And we all take on what we can, which is always too little.”

And what would Rudavsky ask Wiesel now if he were still here to bear witness?

“People ask, post–Oct. 7, what would Elie have said? And I can’t speak for him but I know he would have spoken up from where he comes from. Some would have disagreed with him. But in the U.S. today, when immigrants are being shipped off to places unknown, when people trying to defend them are facing violence, even death, we all need to try to do whatever little bit there is to do.”

Even within disagreement, Wiesel believed in dialogue. Rudavsky, speaking about his relationship with Wiesel’s son, Elisha, said: “We have different political perspectives, but we’re united in saying we’ll keep talking, we’ll keep working together. It’s such a divisive time where people don’t talk to each other — they yell at each other and kill each other. That’s something Elie Wiesel certainly would have spoken up about.”

Because for Wiesel, bearing witness was not only about preserving the past. It was about refusing indifference in the present.

For tickets, visit: themoviehouse.net

Keep ReadingShow less

Marietta Whittlesey

Elena Spellman

When writer and therapist Marietta Whittlesey moved to Salisbury in 1979, she had already published two nonfiction books and assumed she would eventually become a fiction writer like her mother, whose screenplays and short stories were widely published in the 1940s.

“But one day, after struggling to freelance magazine articles and propose new books, it occurred to me that I might not be the next Edith Wharton who could support myself as a fiction writer, and there were a lot of things I wanted to do in life, all of which cost money.” Those things included resuming competitive horseback riding.

Over time, through a career that has spanned writing, emergency medical service and clinical psychology, Whittlesey has built a psychotherapy practice in the Northwest Corner focused on evidence-based treatment for trauma, chronic pain and performance anxiety. Drawing on specialized training in EMDR, a trauma-focused therapy, and clinical hypnosis, she works with clients whose symptoms have often not responded to traditional talk therapy.

Whittlesey grew up in New York City and attended Chapin, an all-girls school widely regarded as one of the best in the country. “I hated it — 12 years of total lack of agency left a mark — but I got a great classical education. Recently, I visited for the first time in more than 30 years and found a delightfully changed school — one I wish I could attend right now,” she laughed.

She studied psychology as an undergraduate at New York University, where she worked in the lab of Dr. Jay Weiss, a MacArthur Fellowship recipient at Rockefeller University and later at the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

After moving to Salisbury, Whittlesey joined the Salisbury Volunteer Ambulance as an EMT and found work writing radio and television spots at the University of Connecticut Health Center in Farmington. That led to a 30-year freelance career writing continuing medical education programs for physicians, often ghostwriting first drafts of journal articles.

“I learned a lot of medicine that way and learned how to speak and write like a doctor, which is essential.” At the same time, she continued to write and co-author nonfiction books. “But after a couple of decades, the 80-hour workweeks and the insane pressure got to me.”

She enrolled in a master’s program in psychology at Capella University, one of the first accredited online universities. “This worked perfectly for me because I could continue to earn a living as a writer during the day.”

After graduating with a Master of Science in clinical psychology, she decided not to pursue a doctorate.

“I am a good autodidact, and I decided I’d rather learn clinical techniques like EMDR and hypnotherapy than do another round of stats and write a dissertation.”

EMDR, or Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing, is a form of psychotherapy most commonly used to help people process and heal from trauma and other distressing life experiences.

After completing a 3,000-hour internship at the former Community Mental Health Affiliates in Lakeville, she opened a private practice in Lakeville. She now works from an office near Sharon Hospital, where she has a general psychotherapy practice. She has a particular interest in treating disorders of appearance, ranging from body dysmorphic disorder to alopecia areata and severe scarring.

Whittlesey is certified by the EMDR International Association in eye movement desensitization and reprocessing.

The therapy follows a specific protocol using bilateral stimulation — through eye movements, pulsars or audio — to help process traumatic memories associated with PTSD.

“So many people have never heard of EMDR, yet it is such a powerful clinical tool — not just for treating trauma, for which it was originally employed, but now with protocols for eating disorders, phobias, anxiety and many other issues. It is considered one of the top evidence-based treatments for trauma by the World Health Organization, the American Psychiatric Association and the Department of Veterans Affairs.”

Whittlesey treats many clients with chronic pain, often stemming from medically unexplained symptoms. Unlike traditional talk therapy — which has an important place, she said — EMDR can sometimes help patients feel significantly better even after a single session.

Rarely are more than six to 10 sessions needed to process traumas such as car accidents, violence or childhood neglect that can lead to a diagnosis of complex PTSD.

“Clinical hypnosis is also very helpful in treating chronic pain, as well as anxiety and addictions. I like to teach people self-hypnosis to use on their own. It has been an extremely useful tool for me throughout my life as a writer with deadlines and as a rider facing a jump course.”

Whittlesey has also launched a performance coaching business, Partners in Performance, where she helps clients overcome performance anxiety. Recent clients have included a golfer with “the yips,” a rider recovering from a bad fall, a teacher accepting an award and a woman studying for a dental hygienist exam.

Asked about future plans, Whittlesey’s eyes lit up as she described upcoming training in Deep Brain Reorienting, a new treatment with some similarities to EMDR.

Whittlesey has a profile on Psychology Today and can be reached at 860-397-5296 or mwlpcllc@gmail.com.

Elena Spellman is a recent Northwest Corner transplant. She is a Russian native and grew up in the Midwest. In addition to writing, she teaches ESL and Russian.

Keep ReadingShow less

Artist Peter Gerakaris in his studio in Cornwall.

Provided

Opening Jan. 17 at the Cornwall Library, Peter Gerakaris’ show “Oculus Serenade” takes its cue from a favorite John Steinbeck line of the artist’s: “It is advisable to look from the tide pool to the stars and then back to the tide pool again.” That oscillation between the intimate and the infinite animates Gerakaris’ vivid tondo (round) paintings, works on paper and mosaic forms, each a kind of luminous portal into the interconnectedness of life.

Gerakaris describes his compositions as “merging microscopic and macroscopic perspectives” by layering endangered botanicals, exotic birds, aquatic life and topographical forms into kaleidoscopic, reverberating worlds. Drawing on his firsthand experiences trekking through semitropical jungles, diving coral reefs and hiking along the Housatonic, Gerakaris composes images that feel both transportive and deeply rooted in observation. A musician as well as a visual artist, he describes his use of color as vibrational — each work humming with what curator Simon Watson has likened to “visual jazz.”

At the heart of the exhibition is a four-foot-diameter hand-painted “Orchid Oculus Tondo,” surrounded by four hand-embellished prints and a shimmering cut-glass mosaic. The central painting conjures a dreamlike cosmos where endangered St. Lucian parrots glide through oversized tropical orchids and foliage. Built through a “call-and-response process” that allows drips, spills and chance encounters to remain visible, the work is alive with motion and improvisation. In the depths of winter, “Oculus Serenade” offers a kind of visual warmth, a reminder of the beauty, fragility and music of the natural world.

“Oculus Serenade: Artwork by Peter D. Gerakaris” runs Jan. 17 through Feb. 28 at the Cornwall Library. An artist’s reception will be held Saturday, Jan. 17, from 4 to 6 p.m. Registration is requested at cornwalllibrary.org/events/.

Keep ReadingShow less

loading