Latest News

The entrance to Torrington Transfer Station.

Photo by Jennifer Almquist

TORRINGTON — Municipalities holding out for a public solid waste solution in the Northwest Corner have new hope.

An amendment to House Bill No. 7287, known as the Implementor Bill, signed by Governor Ned Lamont, has put the $3.25 million sale of the Torrington Transfer Station to USA Waste & Recycling on hold.

The amendment was added after the formation of the Northwest Resource Recovery Authority in Torrington in late May. The text added to the bill reads, “any permit or license relating to the Torrington Transfer Station shall be deemed transferred to the Northwest Resource Recovery Authority, or its designee, and shall continue in full force and effect.”

The change halted the sale to USA, which was unanimously accepted by MIRA Dissolution Authority at its May 14 board meeting, and reopened negotiations with municipal leaders. Torrington is one of two transfer stations in Connecticut, the other being Essex, that are still operated by MIRA-DA. Combined, more than 20 towns currently utilize these facilities.

Members of the Northwest Hills Council of Governments have been working to establish a public option for solid waste management for more than a year. In February 2025, MIRA-DA entered into a term sheet for a regional waste authority to take over the Torrington Transfer Station to be used as a central hub for regional hauling. Those plans were nixed after MIRA-DA’s May decision to privately sell the facility, until the amendment to HB 7287.

The Implementor Bill is “an act concerning the state budget for the biennium ending June 30, 2027,” according to the state website. It was signed by Lamont in early June.

MIRA-DA reviewed the situation at its board meeting Wednesday, June 18. Conversation mostly took place in executive session, but several speakers participated in public comment.

Supporting a public option, Torrington Mayor Elinor Carbone said, “I’m advocating for the local taxpayers for return on the investment that they’ve made over the years through tipping fees.” She continued, “The best way to return that investment is to strongly consider that public option that has been submitted on behalf of the NRRA.”

Selectmen in Cornwall, Falls Village, Goshen, Norfolk, North Canaan, Salisbury and Sharon have all expressed interest in pursuing a public option. Each of these towns continue to haul to Torrington utilizing existing state service agreements, which are due to expire in 2027.

Ed Spinella, attorney representing USA, characterized the Implementor Bill text change as a “rat amendment” that does not affect USA’s proposal. He said he intends to enforce MIRA-DA’s previous acceptance of the sale.

“It’s an enforceable vote and I guarantee you I’m going to make it enforceable,” said Spinella. “We were going to buy the facility regardless of whether or not it had a permit.”

He urged MIRA-DA to produce the necessary paperwork to move forward with the sale.

“I want to sign the documents so we can finish this deal,” said Spinella. “Are you going to be defined by cowering to a rat implementor, rat amendment of the Implementor Bill?”

Following a lengthy executive session June 18 that continued the next day, MIRA-DA recessed without taking action. The meeting was scheduled to continue Monday, June 23, at noon.

Keep ReadingShow less

Juneteenth and Mumbet’s legacy

Jun 18, 2025

Sheffield resident, singer Wanda Houston will play Mumbet in "1781" on June 19 at 7 p.m. at The Center on Main, Falls Village.

Jeffery Serratt

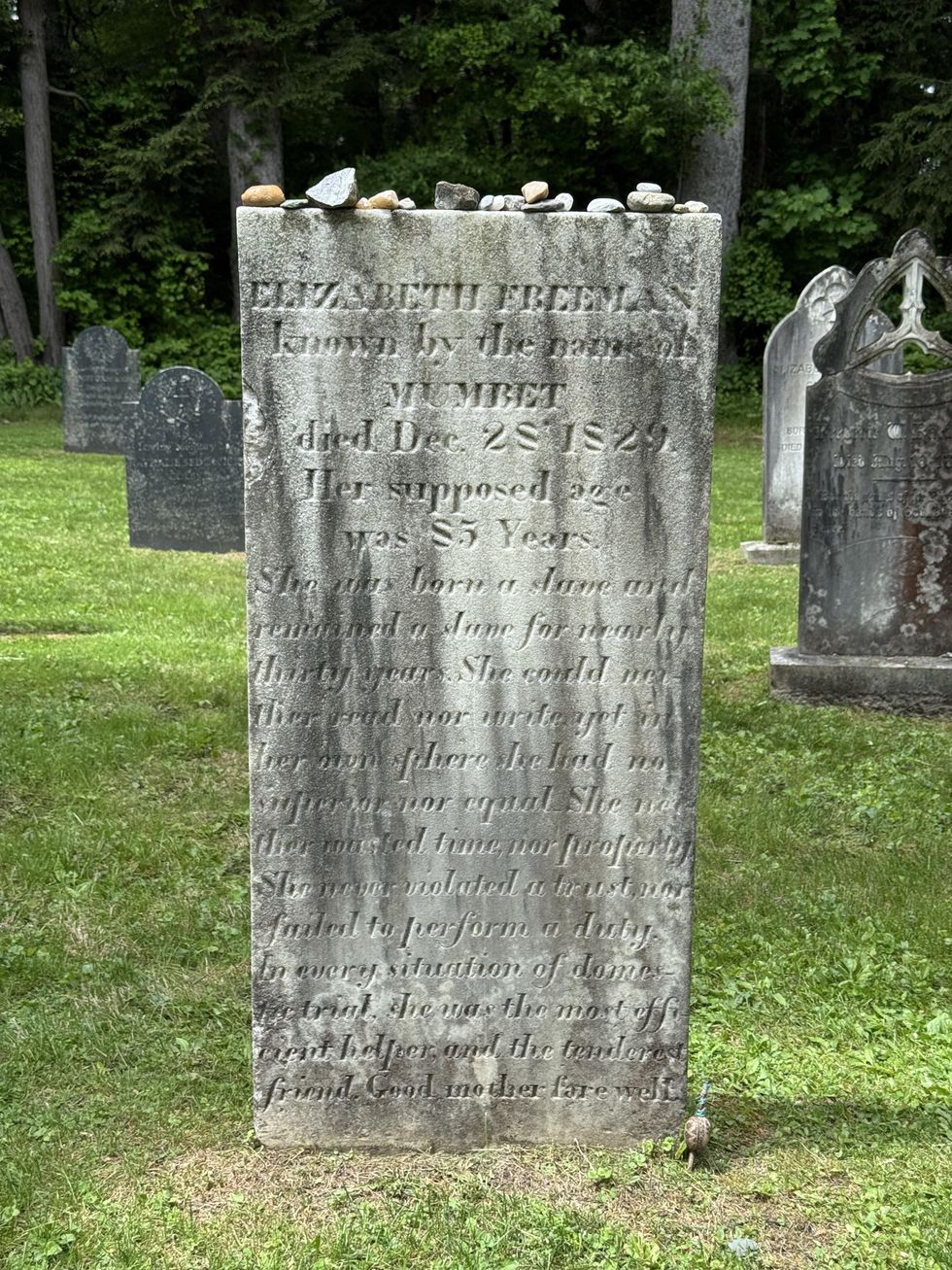

In August of 1781, after spending thirty years as an enslaved woman in the household of Colonel John Ashley in Sheffield, Massachusetts, Elizabeth Freeman, also known as Mumbet, was the first enslaved person to sue for her freedom in court. At the time of her trial there were 5,000 enslaved people in the state. MumBet’s legal victory set a precedent for the abolition of slavery in Massachusetts in 1790, the first in the nation. She took the name Elizabeth Freeman.

Local playwrights Lonnie Carter and Linda Rossi will tell her story in a staged reading of “1781” to celebrate Juneteenth, ay 7 p.m. at The Center on Main in Falls Village, Connecticut.Singer Wanda Houston will play MumBet, joined by actors Chantell McCulloch, Tarik Shah, Kim Canning, Sherie Berk, Howard Platt, Gloria Parker and Ruby Cameron Miller. Musical composer Donald Sosin added, “MumBet is an American hero whose story deserves to be known much more widely.”

Houston has shared the stage with stars ranging from Barbra Streisand to Motown great Mary Wells. “I have had the honor of portraying Elizabeth Freeman for three years in “Meet Elizabeth Freeman” by Teresa Miller. Our first reading of “1781” is in celebration of Juneteenth, which is wonderfully symbolic and poignant.” Juneteenth celebrates the end of slavery. Two years after President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, word of their freedom finally reached slaves in Texas on June 19, 1865.

MumBet, born in 1742 to African enslaved parents, was purchased at age six months by Colonel John Ashley of Sheffield, Massachusetts, for whom she worked until her thirties. Ashley helped write the 1773 Sheffield Declaration which stated, “Mankind in a state of nature are equal, free, and independent of each other, and have a right to the undisturbed enjoyment of their lives, their liberty and property.” Rumor has it that MumBet overheard a reading of the document. After a traumatic household experience, MumBet left the Ashley home in Bartholomew’s Cobble, walked four miles to Sheffield, and asked attorney and abolitionist Theodore Sedgwick to help her gain her freedom.

Houston shared, “I live in Sheffield near where she was enslaved, in a house she would have passed on her walk from Ashley Falls to Sheffield. I am humbled by the fortitude and inner strength it must have taken for this woman to defy norms and take a stand for her own freedom.We Americans must still stand and fight for our rights to live free.”

Elizabeth Freeman spent her years as a free woman working for wages in the Sedgewick household, saving money to buy her own home in Stockbridge, where she was a midwife and healer. She died in 1829 and is buried in “Sedgewick Pie,” the family burial plot in Stockbridge. One of her great-grandchildren, W.E.B. DuBois, born in Great Barrington, was the first African American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard. DuBois founded the NAACP.

Her tombstone reads: “She was born a slave and remained a slave for nearly thirty years. She could neither read nor write yet in her own sphere she had no superior or equal. She neither wasted time nor property. She never violated a trust nor failed to perform a duty. In every situation of domestic trial, she was the most efficient helper, and the tenderest friend. Good mother, farewell.”

The performance of “1781” will take place Thursday, June 19 at 7 p.m. at The Center on Main (103 Main St., Falls Village).Admission is free, donations gratefully accepted.

Keep ReadingShow less

The new mural painted by students at Saint John Paul The Great Academy in Torrington, Connecticut.

Photo by Kristy Barto, owner of The Nutmeg Fudge Company

Thanks to a unique collaboration between The Nutmeg Fudge Company, local artist Gerald Incandela, and Saint John Paul The Great Academy in Torrington, Connecticut a mural — designed and painted entirely by students — now graces the interior of the fudge company.

The Nutmeg Fudge Company owner Kristy Barto was looking to brighten her party space with a mural that celebrated both old and new Torrington. She worked with school board member Susan Cook and Incandela to reach out to the Academy’s art teacher, Rachael Martinelli.

“When Susan and Gerald brought this to me, I immediately saw it as a chance for my students to make something meaningful and lasting,” said Martinelli. “It wasn’t just about painting a wall, it was about teaching kids to serve their community through their art.”

Martinelli introduced the project as an after-school club for grades four through eight. “I wanted students who were truly committed,” she explained. Interest was so high that she had to divide participants into rotating grade-level groups, with occasional full-team days for collaboration. The mural became a long-term endeavor, stretching across a school year and a half.

The painting was created on canvas, a nearly 4’ x 27’ roll, donated by Incandela. The paint came courtesy of school principal Ed Goad. With materials secured, the students dove into research, studying maps, landmarks, and city history to inform their designs. “They worked to capture the spirit of Torrington,” Martinelli said. “But also, to match the whimsy of a candy shop.”

The result is a mural that features a playful “candyland” version of the city, where important buildings and landmarks are sized according to their importance to both the client and the community. “They created this hierarchy of bubbles and buildings, this joyful visual story,” Martinelli said. “It’s full of life.”

Beyond art skills, Martinelli witnessed her students develop qualities often harder to teach: teamwork, communication, resilience. “They learned to scale up sketches, mix large batches of paint for consistency, and adapt their work when it overlapped with someone else’s. They really respected each other’s contributions.”

The project also reflected the Academy’s Catholic STREAM (Science, Technology, Religion, Engineering, Arts, and Math) approach to education. “This was STREAM in action,” Martinelli explained. “They used technology to scale and transfer designs, applied math for proportions and spacing, and worked collaboratively to problem-solve. But they also lived their faith — through service, solidarity, and joy.”

Martinelli believes the mural speaks as much to the process as it does to the final product. “Some of the kids who worked on it have already graduated, but they’re coming back for the unveiling. That says something.”

The unveiling of the mural will take place at The Nutmeg Fudge Company on June 11, from 5:00 to 7:00 p.m., where families, friends, and community members are invited to celebrate the students’ achievement.

Asked what stood out most from the experience, Martinelli said, “For me, the most rewarding part was watching a diverse group of kids work together — different grades, different friend groups — all collaborating with respect, flexibility, and positivity. They created something beautiful, together.”

Keep ReadingShow less

loading