Latest News

Classifieds - December 4, 2025

Dec 03, 2025

Help Wanted

CARE GIVER NEEDED: Part Time. Sharon. 407-620-7777.

SNOW PLOWER NEEDED: Sharon Mountain. 407-620-7777.

Weatogue Stables has an opening: for a part time or full time team member. Experienced and reliable please! Must be available weekends. Housing a possibility for the right candidate. Contact Bobbi at 860-307-8531.

Services Offered

Deluxe Professional Housecleaning: Experience the peace of a flawlessly maintained home. For premium, detail-oriented cleaning, call Dilma Kaufman at 860-491-4622. Excellent references. Discreet, meticulous, trustworthy, and reliable. 20 years of experience cleaning high-end homes.

Hector Pacay Service: House Remodeling, Landscaping, Lawn mowing, Garden mulch, Painting, Gutters, Pruning, Stump Grinding, Chipping, Tree work, Brush removal, Fence, Patio, Carpenter/decks, Masonry. Spring and Fall Cleanup. Commercial & Residential. Fully insured. 845-636-3212.

The Villas Cleaning Team: Owner-Operated. Reliable, detailed cleaning by a trusted husband-and-wife team. Homes & Offices. Airbnb. Small Post-Construction. Commercial. Windows. Laundry. Consistent cleaners every time. Competitive rates. Flexible scheduling. Call/Text: 903-918-2390. Dave Villa for a free estimate.

Auctions, Estate Sales

Estate/Tag Sale: 168 Johnson Road, Falls Village CT. Friday Saturday Sunday, December 5th-7th. Total house contents, furniture, antique and vintage collectables, costume jewelry, shed stuff, basement stuff, stairs chairlift, some art. Fri, Sat 9-4 and Sunday 9-noon. A Tommy sale, come and get it!!

Real Estate

PUBLISHER’S NOTICE: Equal Housing Opportunity. All real estate advertised in this newspaper is subject to the Federal Fair Housing Act of 1966 revised March 12, 1989 which makes it illegal to advertise any preference, limitation, or discrimination based on race, color religion, sex, handicap or familial status or national origin or intention to make any such preference, limitation or discrimination. All residential property advertised in the State of Connecticut General Statutes 46a-64c which prohibit the making, printing or publishing or causing to be made, printed or published any notice, statement or advertisement with respect to the sale or rental of a dwelling that indicates any preference, limitation or discrimination based on race, creed, color, national origin, ancestry, sex, marital status, age, lawful source of income, familial status, physical or mental disability or an intention to make any such preference, limitation or discrimination.

Tag Sales

Sharon, CT

TAG SALE: SATURDAY, DECEMBER 6, 10:00 AM - 2:00 PM, 135 Sharon Mountain Road, Sharon, CT 06069. Clearing things out before the holidays! Stop by for a great mix of items, including: Kitchenware, Small pieces of art, A few pieces of furniture, Clothing, Books, And more assorted household items. Easy to find, everything priced to sell. Hope to see you there!

Keep ReadingShow less

Legal Notices - December 4, 2025

Dec 03, 2025

LEGAL NOTICE

TOWN OF CANAAN/FALLS VILLAGE

NEW OFFICE HOURS: Monday 9am-Noon & Thursday 8am-11am.

Pursuant to Sec. 12-145 of the Connecticut statutes, the Tax Collector, Town of Canaan gives notice that she will be ready to receive Supplemental Motor Vehicle taxes and the 2nd installment of Real Estate & Personal Property taxes due January 1, 2026 at the Canaan Town Hall, PO Box 47, 108 Main St., Falls Village, CT 06031.

Payments must be received or postmarked by February 2, 2026 to avoid interest.

All taxes remaining unpaid after February 2, 2026 will be charged interest from January 1, 2026 at the rate of 1.5% for each month from the due date of the delinquent tax to the date of payment, with a minimum interest charge of $2.00. Sec. 12-146

Failure to receive a tax bill does not relieve the taxpayer of their responsibility for the payment of taxes or delinquent charges. Sec.12-30

Rebecca Juchert-Derungs, CCMC

12-04-25

01-22-26

Notice of Decision

Town of Salisbury

Zoning Board of Appeals

Notice is hereby given that the following application was denied by the Zoning Board of Appeals of the Town of Salisbury, Connecticut on November 25, 2025:

Application #2025-0299 for request for variance to maximum building coverage in the LA Zone on the basis of reduction in nonconforming impervious surface. The property is shown on Salisbury Assessor’s Map 46 as Lot 04 and is known as 26 Ethan Allen Street, Lakeville, Connecticut. The owners of the property are Lowell Goss and Kristen Culp.

Any aggrieved person may appeal this decision to the Connecticut Superior Court in accordance with the provisions of Connecticut General Statutes §8-8.

Salisbury Zoning

Board of Appeals

Lee Greenhouse,

Secretary

12-04-25

NOTICE TO CREDITORS

ESTATE OF

SHIRLEY W. PEROTTI

Late of Sharon

AKA Shirley Perotti

(25-00439)

The Hon. Jordan M. Richards, Judge of the Court of Probate, District of Litchfield Hills Probate Court, by decree dated November 18, 2025, ordered that all claims must be presented to the fiduciary at the address below. Failure to promptly present any such claim may result in the loss of rights to recover on such claim.

The fiduciaries are:

Sarah P. Medeiros

and John F. Perotti

c/o Linda M Patz

Drury, Patz & Citrin, LLP

7 Church Street, P.O. Box 101

Canaan, CT 06018

Megan M. Foley

Clerk

12-04-25

NOTICE TO CREDITORS

ESTATE OF

ESTELLE M. GORDON

Late of Sharon

AKA ESTELLE GORDON

(25-00436)

The Hon. Jordan M. Richards, Judge of the Court of Probate, District of Litchfield Hills Probate Court, by decree dated November 20, 2025, ordered that all claims must be presented to the fiduciary at the address below. Failure to promptly present any such claim may result in the loss of rights to recover on such claim.

The fiduciary is:

Catherine Woolston

c/o Michael Peter Citrin

Drury, Patz & Citrin, LLP

7 Church Street, PO Box 101

Canaan, CT 06018

Megan M. Foley

Clerk

12-04-25

NOTICE TO CREDITORS

ESTATE OF

ELIZABETH SHULTZ

Late of North Canaan

AKA Julila Elizabeth Shultz

(25-00430)

The Hon. Jordan M. Richards, Judge of the Court of Probate, District of Litchfield Hills Probate Court, by decree dated November 20, 2025, ordered that all claims must be presented to the fiduciary at the address below. Failure to promptly present any such claim may result in the loss of rights to recover on such claim.

The fiduciary is:

Paul F. Pfeiffer

c/o Brian McCormick

Ebersol, McCormick & Reis, LLC, 9 Mason Street, PO Box 598, Torrington, CT 06790

Megan M. Foley

Clerk

12-04-25

NOTICE TO CREDITORS

ESTATE OF

GERALD S. SCOFIELD

Late of West Cornwall

(25-00228)

The Hon. Jordan M. Richards, Judge of the Court of Probate, District of Litchfield Hills Probate Court, by decree dated November 20, 2025, ordered that all claims must be presented to the fiduciary at the address below. Failure to promptly present any such claim may result in the loss of rights to recover on such claim.

The fiduciary is:

Linda Scofield

c/o Andrea, Doyle Asman

Litwin Asman, PC, 1047 Bantam Rd., P.O. Box 698, Bantam, CT 06750

Megan M. Foley

Clerk

12-04-25

Keep ReadingShow less

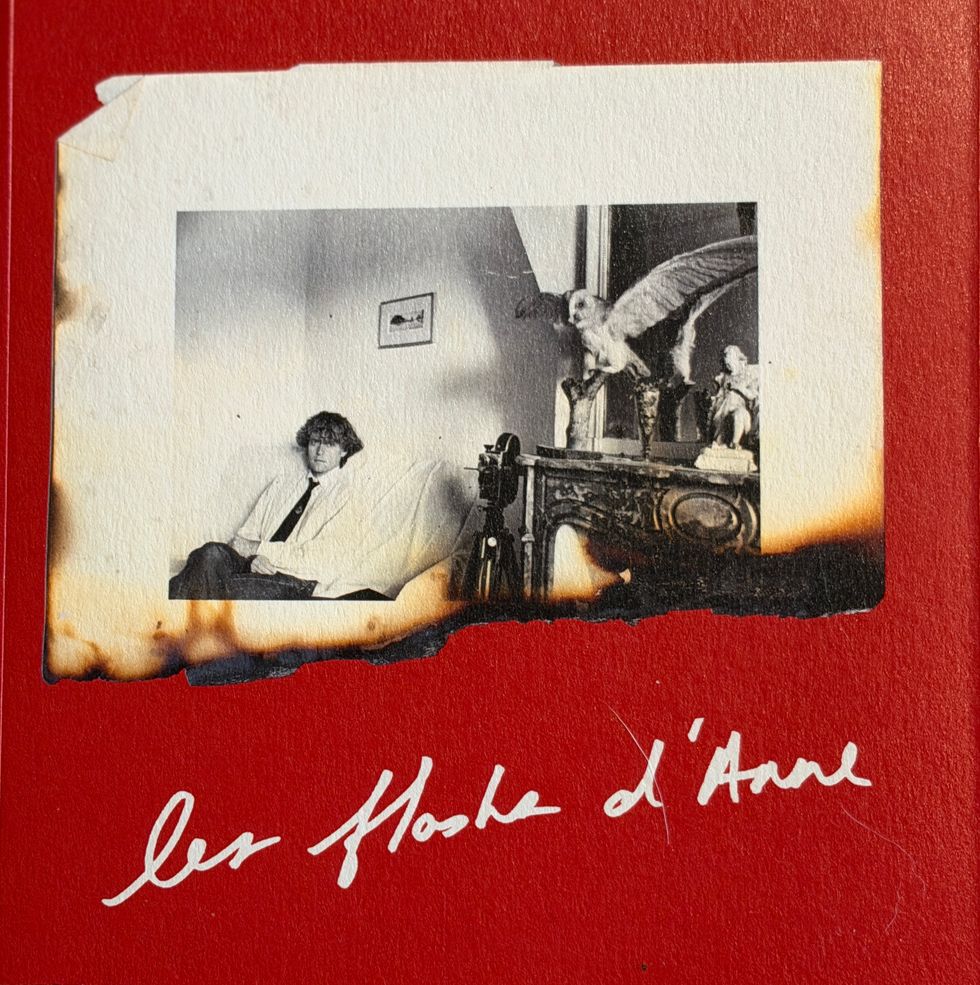

‘Les Flashs d’Anne’: friendship, fire and photographs

‘Les Flashs d’Anne’: friendship, fire and photographs

Anne Day is a photographer who lives in Salisbury. In November 2025, a small book titled “Les Flashs d’Anne: Friendship Among the Ashes with Hervé Guibert,” written by Day and edited by Jordan Weitzman, was published by Magic Hour Press.

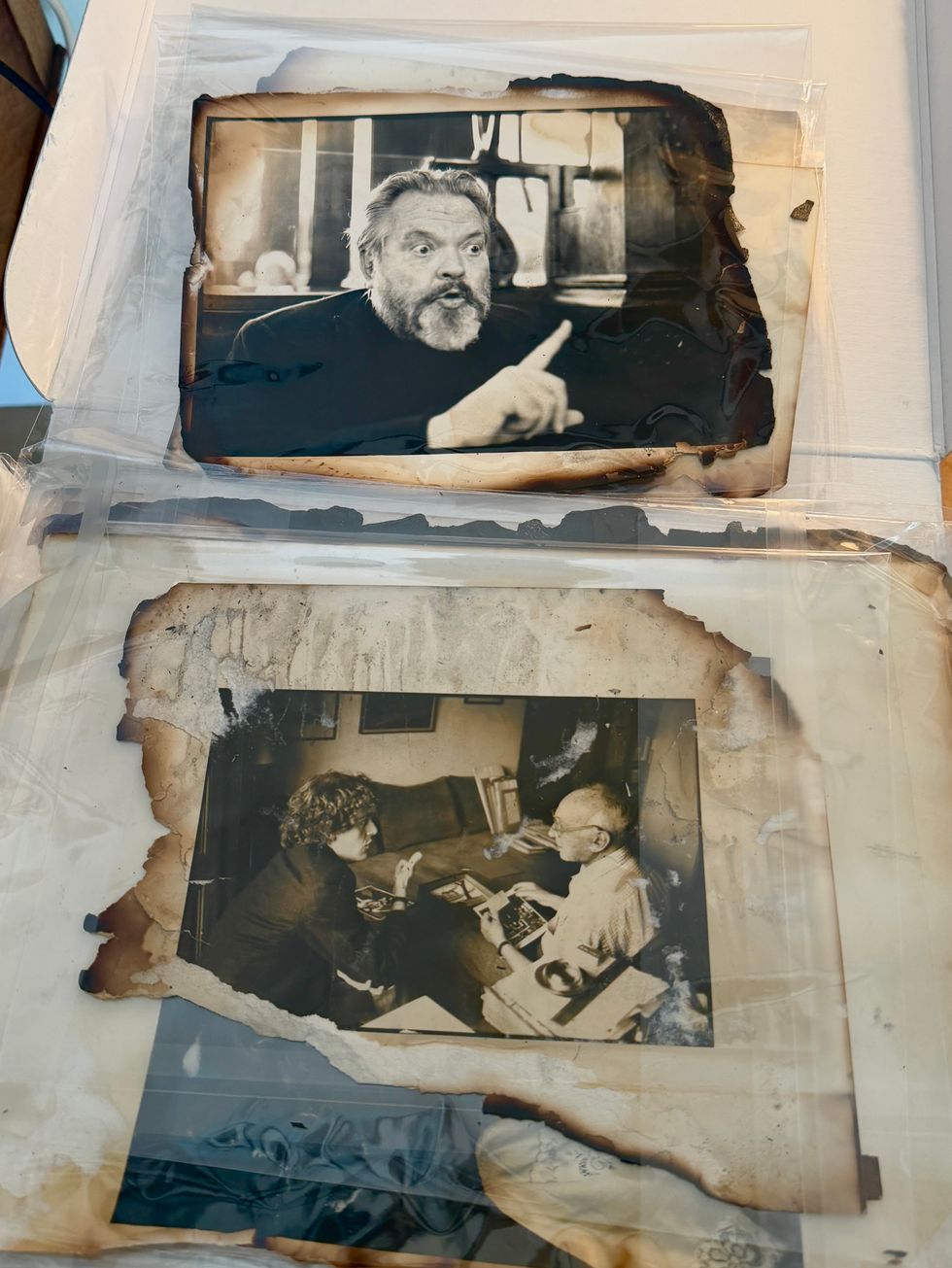

The book features photographs salvaged from the fire that destroyed her home in 2013. A chronicle of loss, this collection of stories and charred images quietly reveals the story of her close friendship with Hervé Guibert (1955-1991), the French journalist, writer and photographer, and the adventures they shared on assignments for French daily newspaper Le Monde. The book’s title refers to an epoymous article Guibert wrote about Day.

On Dec. 11, at 6:30 p.m., at the White Hart Inn in Salisbury, Day and Weitzman will share their memories in a conversation moderated by noted designer Matthew Patrick Smyth. The event is organized by Oblong Books and the Scoville Library.

Fresh home from her exhibition and book signing in Paris, Day sat in her Salisbury aerie high above the distant hills, her daughter’s black cat on her lap. She told the story of “Les Flashs d’Anne,” and the kismet that spurred its evolution.

In 2024, afterlearning that Day had worked with Guibert in New York and Paris, Weitzman — the author of numerous books about Guibert —saw her salvaged images, sought her out and announced, “We must do a book together.”

Weitzman writes in the book’s prologue, “This book is the dreamlike, uncanny result of that serendipitous encounter with a remarkable woman.”

During the 1980s, Day was a working photographer living on Fifth Avenue. A friend, the editor of Le Monde, asked whether Guibert, on his maiden voyage to New York, could stay with her. “I remember it was a cold night when Hervé showed up at my door,” she said.“His flight had just gotten in from Paris and he had this big box of Guerlain perfume. It was wrapped in beautiful pink paper. Within four minutes, we were friends.”

Thus began a whirlwind collaboration that took them from Manhattan, where they interviewed André Kertész, to Paris where they dined with Henri Cartier-Bresson and Duane Michals, and on to interviews with Isabelle Huppert, Gina Lollobrigida, designer Madeleine Castaing, Orson Welles and other luminaries of that time.

Day never saw Guibert after 1983. “Hervé got AIDS in the late ’80s and was quite militant. He now has a following of young people,” Day saidwistfully. During his final days, Guibert wrote five books based on his existential journey.

Day recalled the devastating house fire in which her family tragically lost their friend Maria Paz Reyes and their dog. Day survived by jumping from the second story. A lifetime of images, negatives and slides were lost or damaged. “To lose pictures is like losing friends. Everything was piled into metal file cabinets in my studio. All my negatives and slides were packed in tight. The fire started at the farthest point from there as possible. It was the only thing that wasn’t destroyed— every other single thing was gone. Nothing left. It was raining, so my friend Christopher covered everything with a tarp. The fabulous part of this story is how much help I had from my town, which gave me the empty firehouse to lay out everything to dry. Friends came from near and far to help. Some days I had ten volunteers, and it went on for a month, which gave me something to move forward with. It was so tragic and awful.”

A veteran photojournalist, portrait, wedding, and architectural photographer, Day created images for five books featuring the architecture of the Library of Congress, the U.S. Capitol, and the New York Public Library. She covered events in Cuba, Haiti and South Africa, where she took an iconic image of Nelson Mandela emerging from his prison cell. Her commissioned images of four Presidential Inaugurations are featured in the Smithsonian. Her work has appeared in Newsweek, Time, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Fortune, Paris Match and Vogue. She was the editor of Compass at the Lakeville Journal and The Millerton News.

Currently, she enjoys shooting digital photographs of nature. “I am interested in migration, large groups of birds and insects. I’ve been to New Mexico to photograph monarchs, Nebraska to photograph Sandhill cranes, and Ireland to photograph a murmuration of starlings.”

Day summed up her life: “Things just happened to me.”

Tickets to the event at The White Hart Inn on Dec. 11 are available at oblongbooks.com

Keep ReadingShow less

Writer and performer Nurit Koppel

Provided

In 1983, writer and performer Nurit Koppel met comedian Richard Lewis in a bodega on Eighth Avenue in New York City, and they became instant best friends. The story of their extraordinary bond, the love affair that blossomed from it, and the winding roads their lives took are the basis of “Apologies Necessary,” the deeply personal and sharply funny one-woman show that Koppel will perform in an intimate staged reading at Stissing Center for Arts and Culture in Pine Plains on Dec. 14.

The show humorously reflects on friendship, fame and forgiveness, and recalls a memorable encounter with Lewis’ best friend — yes, that Larry David — who pops up to offer his signature commentary on everything from babies on planes to cookie brands and sports obsessions.

Koppel has good friends in the Pine Plains area and she calls the opportunity to present the piece at the Stissing Center a gift to her and her artistic process, which she shares with her son, Gideon McCarty, who serves as her director and dramaturg.

“He is the one person I listen to,” said Koppel.She credited him with helping her shape, in her own words, “real events from her life with Lewis.” For Mother’s Day this year, McCarty gave her the time to further develop the material and Koppel worked uninterrupted for 12 hours to hone and bring the piece to its current form. She plays 11 characters, not through impersonation but by presenting their authentic voices.

Koppel is clear that writing this piece was the right way for her to respond to Lewis’ passing in 2024, and that theatre is the right way to share it with others. “I wanted to have artistic control over the development process,” she said, and to bring to life her romantic relationship with Lewis, their experiences in New York City comedy clubs, and their neurotic New York friends. She also is open to opportunities to expand further on the material, perhaps in film or TV, as she still has a lot to say.

Koppel hopes primarily that people will be entertained by the world of the play. “I’m a pie-in-the-face kind of person and I want the play to give everyone a good laugh.” Considering her cast of characters, “Apologies Necessary” promises to offer plenty of laughs —plus much more.

“‘Apologies Necessary’ continues Stissing Center’s tradition to serve as a platform for new works of theater, providing playwrights with the opportunity to showcase their work and hone their craft,” said Patrick Trettenero, executive director of the Stissing Center. “We are excited to have Nurit present this reading of her new work in progress.”

Running time: approx. 90 minutes. Sunday, Dec. 14 at 7 p.m., Downstairs at Stissing Center. Tickets are vailable at thestissingcenter.org or 518-771-3339.

Richard Feiner and Annette Stover have worked and taught in the arts, communications, and philanthropy in Berlin, Paris, Tokyo, and New York. Passionate supporters of the arts, they live in Salisbury and Greenwich Village.

Keep ReadingShow less

loading