Latest News

Harding launches 2026 campaign

Jan 29, 2026

State Sen. Stephen Harding

Photo provided

NEW MILFORD — State Sen. and Minority Leader Stephen Harding announced Jan. 20 the launch of his re-election campaign for the state’s 30th Senate District.

Harding was first elected to the State Senate in November 2022. He previously served in the House beginning in 2015. He is an attorney from New Milford.

In his campaign announcement, he said, “There is still important work to do to make Connecticut more affordable, government more accountable, and create economic opportunity. I’m running for reelection to continue standing up for our communities, listening to residents, and delivering real results.”

As of late January, no publicly listed challenger has filed to run against him.

The 30th District includes Bethlehem, Brookfield, Cornwall, Falls Village, Goshen, Kent, Litchfield, Morris, New Fairfield, New Milford, North Canaan, Salisbury, Sharon, Sherman, Warren, Washington, Winchester and part of Torrington.

Keep ReadingShow less

Specialist Directory Test

Jan 29, 2026

James Cookingham

Jan 28, 2026

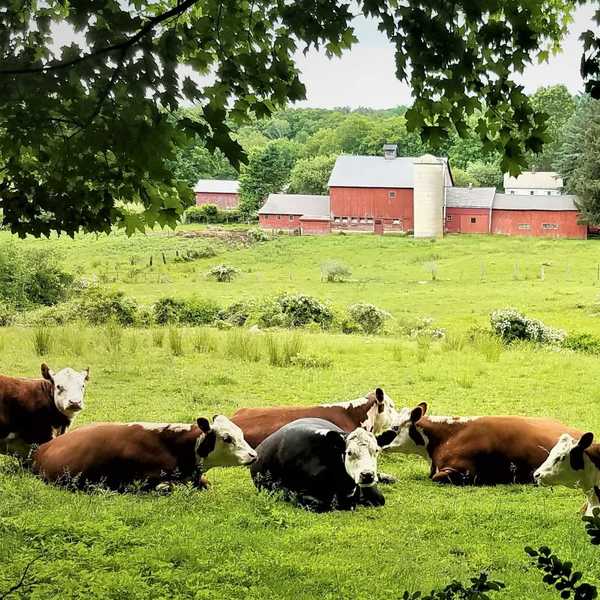

MILLERTON — James (Jimmy) Cookingham, 51, a lifelong local resident, passed away on Jan. 19, 2026.

James was born on April 17, 1972 in Sharon, the son of Robert Cookingham and the late Joanne Cookingham.

He attended Webutuck Central School.

Jimmy was an avid farmer since a very young age at Daisey Hill and eventually had joint ownership of Daisey Hill Farm in Millerton with his wife Jessica.

He took great pride in growing pumpkins and sweet corn.

He was very outdoorsy and besides farming, loved to ride four wheelers, fish, and deer hunt. He also loved to make a roaring bonfire.

He was a farmer, friend, husband, father, son and brother. He will be missed by many.

He is survived by his father, Robert Cookingham, wife Jessica (Ball) Cookingham, daughters, Hailey Cookingham-Loiodice (Matt), Taylor Ellis-Tanner (Jimmy) and sister Brenda Valyou, as well as many cousins, nieces and nephews.

He is predeceased by his mother, Joanne (Palmer) Cookingham.

His daughter, Hailey, will always keep his legacy alive by their father-daughter antics, such as their handshake, nicknames and making “quacking noises” at each other.

Services/Memorials will be held at a later date.

The Kenny Funeral Home has care of arrangements.

Keep ReadingShow less

loading

Telecom Reg’s Best Kept On the Books

When Connecticut land-use commissions update their regulations, it seems like a no-brainer to jettison old telecommunications regulations adopted decades ago during a short-lived period when municipalities had authority to regulate second generation (2G) transmissions prior to the Connecticut Siting Council (CSC) being ordered by a state court in 2000 to regulate all cell tower infrastructure as “functionally equivalent” services.

It is far better to update those regs instead, especially for macro-towers given new technologies like small cells. Even though only ‘advisory’ to the CSC, the preferences of towns by law must be taken into consideration in CSC decision making. Detailed telecom regs – not just a general wish list -- are evidence that a town has put considerable thought into where they prefer such infrastructure be sited without prohibiting service that many – though not all – citizens want and that first responders rely on for public safety.

Such regs come in handy when egregious tower sites are proposed in sensitive areas, typically on private land. The regs are a town’s first line of defense, especially when cross referenced to plans of conservation and development, P&Z regulations, and wetlands setbacks. They identify how/where the town plans to intersect with the CSC process. They are also a roadmap for service providers regarding preferred sites and sometimes less neighborhood contention. In fact, to have no telecom regs can weaken a town’s rights to protect environmental, scenic, and historic assets, and serve up whole neighborhoods to unnecessary overlapping coverage and corporate overreach. Such regs are unique to every town and should not follow anyone else’s boiler plate, especially industry’s.

Connecticut is the only state that has a centralized siting entity for cell towers. The good news is that applicants must prove need for new tower sites in an evidentiary proceeding and any decisions have the weight of the state behind them. The bad news is that the CSC used to be far less industry-friendly and rote in their reviews, which now resemble a check list. There is an operative assumption at CSC that if an applicant wants a tower, they must need it, otherwise why spend significant money to run the approval gauntlet? This reflects a subtle shift over the years at CSC from sincere willingness to protect the environment toward minimal tweaking of bad applications with minor changes. The bottom line is that towns really cannot rely on the CSC to do all the work for them.

What CSC issues telecom providers is a “certificate of environmental compatibility” after an evidentiary proceeding (not unlike a court case) with intervenors, parties, expert witnesses, and the service provider’s technical pro’s sworn in and subject to cross examination. Service providers get to do the same with any opposition from intervenor/party participants – like towns and citizens -- and their experts. It’s an impressive process whose ultimate goal is the fine balancing between allowing adequate/reliable public services and protecting state ecology with minimal damage to scenic, historic, and recreational values. They unfortunately often fall short of their mandate – like approving cell towers with diesel generators over town aquifers -- evidenced by CSC only rejecting about five cell towers in the past 15-20 years.

The CSC was founded in 1972 and clarified its mission in the 1980’s to prevent the state from being carved up willy-nilly by gas pipelines, high tension corridors, and broadcast towers. With the sudden proliferation of cell towers beginning in late 1990’s, it became the most sued agency in Connecticut by both an arrogant upstart industry if applications were denied and by towns/citizens when bad sites were forced on them. CSC gradually formed a defensive posture that drives their decisions toward industry with deeper pockets and attorneys on retainer.

For citizens, nothing can wreck one’s day like the CSC. It behooves towns to protect what little toolkit they have, and understand the legal parameters of the CSC’s playing field. The CSC is not a “normal” government agency where municipal/citizen redress is based on logic and local support. Their process is largely immune to everything but specific kinds of evidence – like town regs with setbacks/fall zones, radio frequency transmission signal strengths, sensitive areas identified, and detailed wildlife inventory, among others.

There is a current cell tower fight involving two intervening towns -- Washington and Warren; both with good cell tower regs – over a tower site within 1200’ of a Montessori School, near Steep Rock’s nature preserves with comprehensive geology/wildlife databases that include endangered, threatened and special concern flora and fauna, on established federal/state migratory bird flyways, within throwing distance to a historic site capable of being listed on the Underground Railroad, and with an access road on a blind curve entering a state highway that will permanently damage wetlands, vernal pools, and core forests. There are well credentialed environmental experts, including Dr. Michael Klemens, former chair of Salisbury’s P&Z, as well as the former director of migratory bird management at the US Fish and Wildlife Service, and an RF engineer testifying to alternative approaches, plus three attorneys representing intervenors. It is the most professional challenge I have seen at CSC since Falls Village successfully mounted one that protected Robbins Swamps several years ago.

The hearing is ongoing, with uncertain results. To see what it takes today to stop an inappropriate tower siting, see Docket #543 under “Pending Matters” at https://portal.ct.gov/csc before removing local cell tower regs – the lowest hanging fruit that any town can possess in case it’s needed.

B, Blake Levitt is the Communications Director at The Berkshire-Litchfield Environmental Council. She writes about how technology affects biology.