Latest News

Joan Jardine

Oct 29, 2025

TORRINGTON — Joan Jardine, 90, of Mill Lane, passed away at home on Oct. 23, 2025. She was the loving wife of David Jardine.

Joan was born Aug. 9, 1935, in Throop, Pennsylvania, daughter of the late Joseph and Vera (Ezepchick) Zigmont.

Joan graduated from Harding High School.

She was a working artist for much of her adult life, starting her career studying plein air impressionist oil painting at the Cape Cod School of Art. Her work evolved to include a more representational style, and eventually a large body of abstract pieces. Her award-winning work has been shown in galleries and juried art shows throughout southern New England.

She is survived by her daughter Leslie and her husband George, brothers Joseph, Victor, and their families, nephews Gregory, Christopher, and their families, daughter-in- law Huong, and the extended Jardine family. She was predeceased by her son Douglas, and brother Michael.

A memorial service will be held at All Saints of America Orthodox Church, 313 Twin Lakes Road, Salisbury, Connecticut on Thursday, Oct. 30, at 10 a.m. Memorial contributions may be made to the All Saints of America Orthodox Church, PO Box 45, Salisbury, CT 06068.

The Kenny Funeral Home has care of arrangements.

Keep ReadingShow less

The ofrenda at Race Brook Lodge.

Lety Muñoz

On Saturday, Nov. 1, the Race Brook Lodge in Sheffield will celebrate the Mexican Day of the Dead: El Día de los Muertos.

Mexican Day of the Dead takes place the first weekend of November and honors los difuntos (the deceased) with ofrendas (offerings) on an altar featuring photos of loved ones who have passed on. Elements of earth, wind, fire and water are represented with food, papel picada (colorful decorative paper), candles and tequila left for the beloved deceased. The departed are believed to travel from the spirit world and briefly join the living for a night of remembrance and revelry.

Music and events programmer Alex Harvey has been producing Día de los Muertos at Race Brook for the past three years, and with the closing of the venue looming, the festival takes on a deep and personal meaning.

“The anchoring gesture of Race Brook, long before I arrived on the scene, has always been to cultivate a space that thins the veil between the worlds. Something otherworldly is hiding in the mountain’s towering shadow: the whispering spring-fed stream, the dense lineage that founder Dave Rothstein brings, the woodsmoke that rises every night of the year from the firepits. This space communes with the spirits,” said Harvey.

“And so we cradle a special ache in our hearts as the leaves turn and the beautiful dance of Race Brook’s project of cultural pollination draws to a close. Fitting, then, to return for one last activation — Día de Los Muertos — a celebration of the end of things. A remembrance of those who’ve made the transition we are all destined for, but also a time when we honor many types of loss. And while we will all mourn those who aren’t there in the flesh, we will also, with humility, come as mourners for the space itself,” Harvey continued.

The event will be a night to remember, to celebrate and to release with ritual, music, and communal remembrance. Participants are invited to bring photos, talismans and offerings for the ofrenda (offering), as well as songs, poems or toasts to share in tribute to loved ones who have passed.

Mexican American musicians Maria Puente Flores, Mateo Cano, Víctor Lizabeth, Oviedo Horta Jr. and Andrea from Pulso de Barro, an ensemble rooted in the Veracruz tradition of son jarocho, will be performing.

Translating to “Pulse of the Clay,” their name reflects a deep connection to the earth and to the living heartbeat of culture itself. Through a synthesis of Mexican, Cuban, Venezuelan and Puerto Rican traditions, Pulso de Barro merges poetry, rhythm and communal song as pathways to coexistence with nature. Their performances feature the jarana and leona (stringed instruments), quijada, cajón, maracas, and marimba (percussion), the tarima (percussive dance platform) and a call-and-response of folk and original versadas.

The evening begins at 6 p.m. in the Barn Space with a Fandango de los Muertos featuring Pulso de Barro, a Race Brook favorite. At 8 p.m., the Open Mic for the Dead invites guests to speak directly into the spirit world — through word, music or memory. The night culminates at 10:30 p.m. with a Fandango for the Dead, a participatory music and dance celebration. Bring your instruments, your voices and your dancing shoes.

Race Brook Lodge is a unique rustic getaway destination for relaxation, hiking, live music, workshops, weddings and more. Sadly, it will be closing for good later in 2026, ending a storied chapter of Berkshire music, art, culture and well-being.

Come experience an evening that honors lost loved ones and the end of a Berkshire institution. The cycle of life endures. Surely, resurrection is in the cards for Race Brook Lodge.

For Tickets and info, visit: rblodge.com

Keep ReadingShow less

‘Coming to Light’ at Norfolk Library

Oct 29, 2025

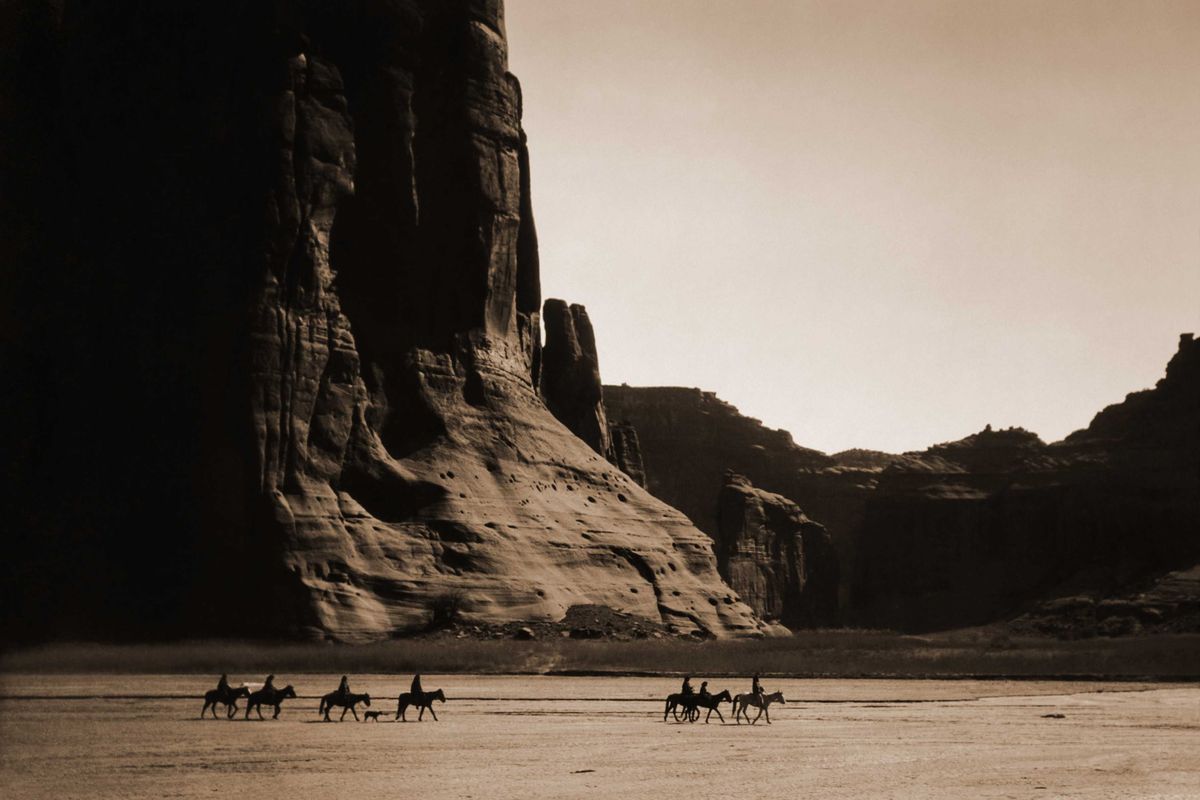

Canyon de Chelly (1904) – Seven Navajo riders on horseback

Edward S. Curtis

At a time when questions of representation, cultural legacy and historical narratives are at the forefront of public conversation, the Norfolk Library’s upcoming screening of the award-winning documentary “Coming to Light” offers a timely opportunity for reflection.

The event will be held on Thursday, Nov. 6, at 5:30 p.m., and will include a post-screening discussion with the film’s director, Lakeville resident Anne Makepeace.

“Coming to Light” offers a deeply researched, visually rich portrait of photographer Edward S. Curtis, whose early 20th century mission to record Native American life resulted in tens of thousands of images, sound recordings and texts.

But the film goes beyond biography, critically examining Curtis’ romanticized vision of Native American life and engaging with the descendants and communities whose lives and traditions the photo archives continue to affect.

Between 1896 and 1914, Curtis photographed over 80 tribes from Arizona to Alaska in an effort to capture Native American cultures he feared were disappearing..

“Curtis saw cultural genocide going on, and he feared these cultures would disappear,” Makepeace said. “He wanted to show these people are still here and these traditions are still happening.”

In the late 1990s, when Makepeace was developing her film on Curtis — about a century after he had started his photographic work — she wanted to see how present-day Native Americans felt about his photographs. She found that while academics had long derided Curtis’ work as extractive, colonialist, and often staged, most Native Americans she spoke with were overwhelmingly appreciative of his work. In fact, some of Curtis’ photographs ultimately helped certain tribes revive specific ceremonies.

“Coming to Light” premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, was shortlisted for an Academy Award in 2000, and was later aired on PBS’ “American Masters” in 2001. As the documentary nears its 25th anniversary, Makepeace reflected on the significance of the film and its lasting impact.

“The film shows the beauty and resilience of these cultures and the diversity of each of the varied tribes that were documented,” she said.

At a time when cultural preservation, national identity and documentary ethics are more important than ever, Makepeace said she believes the film’s message remains especially relevant in 2025.

For further details on the screening and to reserve a seat, visit: norfolklibrary.org/events/documentary-film-coming-to-light/

To see more of Makepeace’s work, visit: makepeaceproductions.com/index.html

Keep ReadingShow less

loading