Latest News

The case of Jacquier vs. Camardi is expected to continue at Torrington Superior Court the week of Sept. 15.

Photo by Riley Klein

NORTH CANAAN — A pair of Democratic Town Committee (DTC) candidates are seeking legal recourse to ensure they are included on the ballot this November despite errors on the party endorsement slate.

Plaintiffs Jean Jacquier and Carol Overby brought the case against defendant Marilisa Camardi to Torrington Superior Court, which held an evidentiary hearing Friday, Sept. 12. Testimony from both sides aimed to explain the situation to Judge Ann E. Lynch.

At the July 22 DTC caucus, Jacquier was endorsed as the party’s candidate for town clerk and Overby was endorsed to run for Board of Finance.

The next day, DTC chair and caucus secretary Chris Jacques filed the full endorsement slate and State Election Enforcement Commission (SEEC) documents to Assistant Town Clerk Marilisa Camardi. But the slate was missing information: Jacquier and Overby were not assigned to a specific office or term.

"I am a rookie at this," Jacques said on the witness stand. "I suppose I just didn't look at it closely enough."

Jacquier testified that she was not wearing her glasses while filling out her information on the official endorsement slate and “made a clerical mistake.”

Overby was not called as a witness.

Camardi testified to noticing on July 24 that the form was missing information and, after cross referencing the accompanying SEEC documents, filled in the blanks herself. It was established during the hearing that making clerical corrections on forms is within proper protocol for a town clerk.

On Aug. 7, however, First Selectman Brian Ohler alerted the Secretary of the State’s (SOTS) office that the original document was incomplete. (Ohler was not present at the Sept. 12 hearing.)

SOTS Election Officer Heather Augeri reviewed the slate as it was originally submitted. Per the filing, she responded that the endorsements were not properly certified and therefore void. Augeri advised Camardi remove both nominees from the ballot.

Jacquier testified that since the Aug. 7 correspondence she has had several phone calls with Augeri, who she described as a friend. Jacquier said Augeri relayed the same message to her: “She said it’s not valid.”

Camardi is the acting town clerk in North Canaan, though she is technically Jacquier’s part-time assistant. Jacquier is the current, four-term elected town clerk but has not reported to work since February following a dispute between her and the first selectman. “I did not resign. I did not quit. I just left,” Jacquier testified. “I couldn’t stand the turmoil.”

Plaintiff attorney John Kennelly said the SOTS office has no statutory authority to rule on issues relating to municipal party endorsements. Kennelly claimed that as the acting town clerk, Camardi is the sole individual responsible for finalizing and certifying the town election ballot.

Kennelly asserted that if Camardi was informed through the SEEC documents of which offices Jacquier and Overby were endorsed for, then Augeri’s advice should be ignored and the two candidates should be eligible to run in November.

Camardi said she was waiting to finalize the ballot until the court makes its decision.

After nearly three hours of testimony, Judge Lynch referenced a similar case, Airey vs. Feliciano (2024), in which Connecticut Supreme Court ruled to reject an improperly signed petition sheet. Lynch requested briefs from each attorney by Monday, Sept. 15, and planned to continue the hearing that week.

Keep ReadingShow less

Wake Robin public hearing closes

Sep 10, 2025

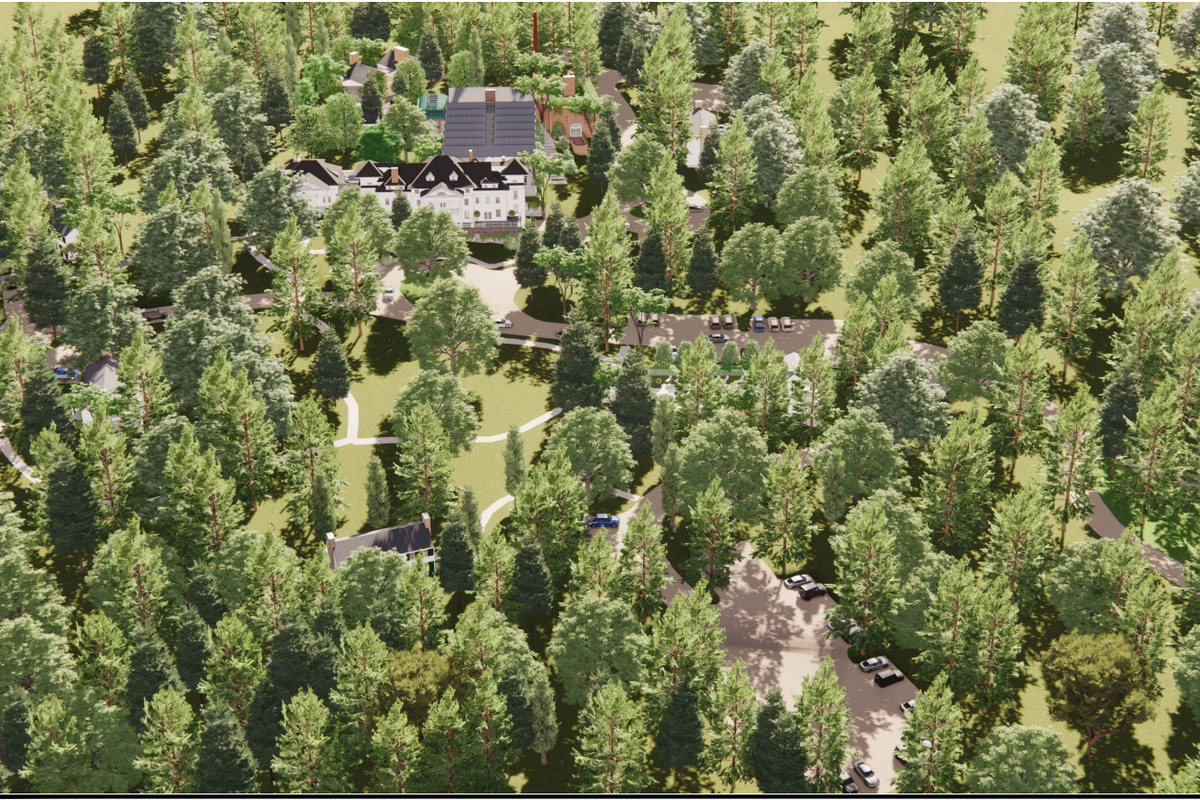

Aradev LLC’s plans to redevelop Wake Robin Inn include four 2,000-square-foot cabins, an event space, a sit-down restaurant and fast-casual counter, a spa, library, lounge, gym and seasonal pool. If approved, guest room numbers would increase from 38 to 57.

Provided

LAKEVILLE — The public hearing for the redevelopment of Wake Robin Inn is over. Salisbury Planning and Zoning Commission now has two months to make a decision.

The hearing closed on Tuesday, Sept. 9, after its seventh session.

Michael Klemens, chair of P&Z, had warned at the opening of the proceedings that “this might be a long night” due to a last-minute influx of material from experts hired by Wells Hill Road residents William and Angela Cruger to oppose the project, but this turned out not to be the case.

These 11th hour submissions set a sour tone to the start of the meeting, with commissioner Robert Riva stating that it was “not very professional to pull this stunt on this Commission.” Riva said he had diligently reviewed the already substantial documentation provided by both the applicant and the opposing experts, and was surprised to find a “dump” of additional information submitted just hours before the meeting’s start time at 6 p.m.

Tensions were quickly eased, however, when William Cruger offered his concise summation of his platform’s opposition to the expansion, which is the second iteration of the project after an earlier version was withdrawn late last year.

“It’s important for you all to hear from me that there was never any disrespect intended to the Commission, the commissioners, and to the process,” Cruger said. He defended the last-minute submissions as an effort on the part of the experts to be thorough in their analysis: “Our intention… has been and remains to do our best to get whatever we think will be helpful in your deliberations into the record.”

The Crugers formally entered the hearing process as intervenors for the first application from Aradev LLC, the applicant, in the fall of 2024, meaning they and their hired consultants had full party status in the hearing proceedings. During this cycle, however, they chose not to petition for intervenor status, yet during this round of hearings their role has been similar. Klemens described them as having “almost intervenor status — not quite.”

William Cruger summarized the consultant’s findings for Aradev’s revised application, noting they found it to be “virtually identical in scale to the previous proposal.”

“Our position is that the proposed expansion would absolutely negatively impact the usefulness, enjoyment and value of the surrounding properties,” he said.

Aradev’s attorney Joshua Mackey countered by saying that the special permit conditions would elevate the currently non-conforming hotel in the zone, describing it as a “community asset that is improved, regulated, and safeguarded for generations to come.” He characterized Aradev as “the next steward of this storied property.”

After Mackey and Aradev co-founder Steven Cohen concluded their remarks, Klemens closed the hearing with no public comment, which he had stated would be the case at last week’s hearing session on Thursday, Sept. 4. Klemens said that P&Z will begin deliberating the proposal in early October after the commissioners have had the chance to review the information in the record.

A total of 45 letters, including the Crugers’ experts’ testimony, were submitted since the Sept. 4 meeting alone, alongside hundreds of pages of application materials and additional testimony.

As the Commission deliberates and reviews, all of this information is available for public viewing on the “Meeting Documents” subpage under P&Z’s section on the town website, www.salisburyct.us.

The Commission must issue a decision on the application by Nov. 13, the end of the statutorily defined deliberation window.

Keep ReadingShow less

Judith Marie Drury

Sep 10, 2025

COPAKE — Judith Marie “Judy” Drury, 76, a four-year resident of Copake, New York, formerly of Millerton, New York, died peacefully on Tuesday, Sept. 2, 2025, at Vassar Bros. Medical Center in Poughkeepsie, New York, surrounded by her loving family and her Lord and savior Jesus Christ. Judy worked as a therapy aide for Taconic DDSO in Wassaic, New York, prior to her retirement on Feb. 1, 2004. She then went on to work in the Housekeeping Department at Vassar Bros. Medical Center for several years.

Born Jan. 2, 1949, in Richford, Vermont, she was the daughter of the late Leo J. and Marie A. (Bean) Martel. She attended Roeliff Jansen Central School in Columbia County, New York, in her early years. Judy was an avid sports fan and she was particularly fond of the New England Patriots football team and the New York Rangers hockey team. She enjoyed spending time with her family and traveling to Florida, Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, and Pennsylvania for many years. She was a longtime parishioner of Faith Bible Chapel of Shekomeko on Silver Mountain in Millerton as well.

Judy is survived by two brothers; John Martel and his wife, Jane of Falls Village, Connecticut, and Frank Martel of Ancram, New York; her sister, Susanna “Sue” Martel of Copake, New York; and three generation of nieces, nephews, great nieces and nephews and great-great nieces and nephews. In addition to her parents, Judy was predeceased by her brother, Leo W. Martel, Sr. of Poughkeepsie, New York, and her sister, Helen J. Slater of Hillsdale, New York; her sister-in-law, Karen Martel of Ancram and a special nephew, Jacob Stickle of Copake.

A visiting hour will take place on Wednesday, Sept. 10, 2025, from 2 p.m. to 3 p.m. at Faith Bible Chapel, 222 Silver Mountain Road, Millerton, New York 12546. A funeral service will be held at 3 p.m. Pastor William Mayhew will officiate. Burial will follow at Irondale Cemetery in Millerton, New York. A celebration of Judy’s life will be announced at a later date. Arrangements have been entrusted to the Scott D. Conklin Funeral Home, 37 Park Avenue, Millerton, New York 12546.

Memorial contributions may be made to Faith Bible Chapel, 222 Silver Mountain Road, Millerton, New York 12546 or American Cancer Society, 45 Reade Place, Poughkeepsie, New York 12601. To send an online condolence to the family, flowers to the service or to plant a tree in Judy’s memory, please visit www.conklinfuneralhome.com

Keep ReadingShow less

Jeremy Dakin

Sep 10, 2025

AMESVILLE — Jeremy Dakin, 78, passed away Aug. 31, 2025, at Vassar Brothers Medical Center after a long battle with COPD and other ailments.

Jeremy was a dear friend to many, and a fixture of the Amesville community. There will be a service in his memory at Trinity Lime Rock Episcopal Church on Sept. 27 at 11 a.m.

Below is the obituary Jeremy himself wrote:

Born July 20, 1947, Pittsfield, Massachusetts.

A resident of Salisbury, Connecticut for over 75 years, he graduated from UVM in 1970, at which time he enlisted in the U.S. Army as a German translator (“It just seemed like a better idea than learning Vietnamese”), and served two years in West Berlin.

Returning to Vermont in 1973 he began a 16-year gig as a ski shop manager and a professional ski patroller, which led to a 30-year stint as an EMT.

A direct descendant of Rebecca Nurse (who was hanged as a witch in Salem in 1692), he is survived by a nephew, Robin Dakin, of Englewood, Ohio, his wife Amy, and a flock of grandnieces, all of whom seem to have inherited the family love of camping and canoeing.

The love of his life, Wren Smith, passed away in 2007 after a 10-year battle with breast cancer. By the time he was seventy, Jeremy’s physical activities were curtailed by COPD, due to a lifetime of smoking.

Rather than spend money on flowers, please consider a donation to the American Cancer Society and/or the American Lung Association. But, for Pete’s sake, don’t smoke.

Keep ReadingShow less

loading