The Quiet Radical President

Biographer C.W. Goodyear Photo courtesy Dystel, Goderich & Bourret

When I think of the lives of the American presidents — excluding perhaps the most recent ones, or those enshrined on Mount Rushmore — I’m reminded how little we remember about them, other than a few fun facts: Carter for his cardigans; Clinton for the Lewinsky scandal; Grant for being an alcoholic; Coolidge for being mute; Tyler for Tippecanoe; Taft for being overweight. In truth, however, history is more complex, and a lot more compelling. Carter, for example, enjoyed a string of successes that are often overlooked, including adding 100 million acres to the park system; appointing a record number of female, Black, and Hispanic citizens to government jobs; helping bring amity between Egypt and Israel.

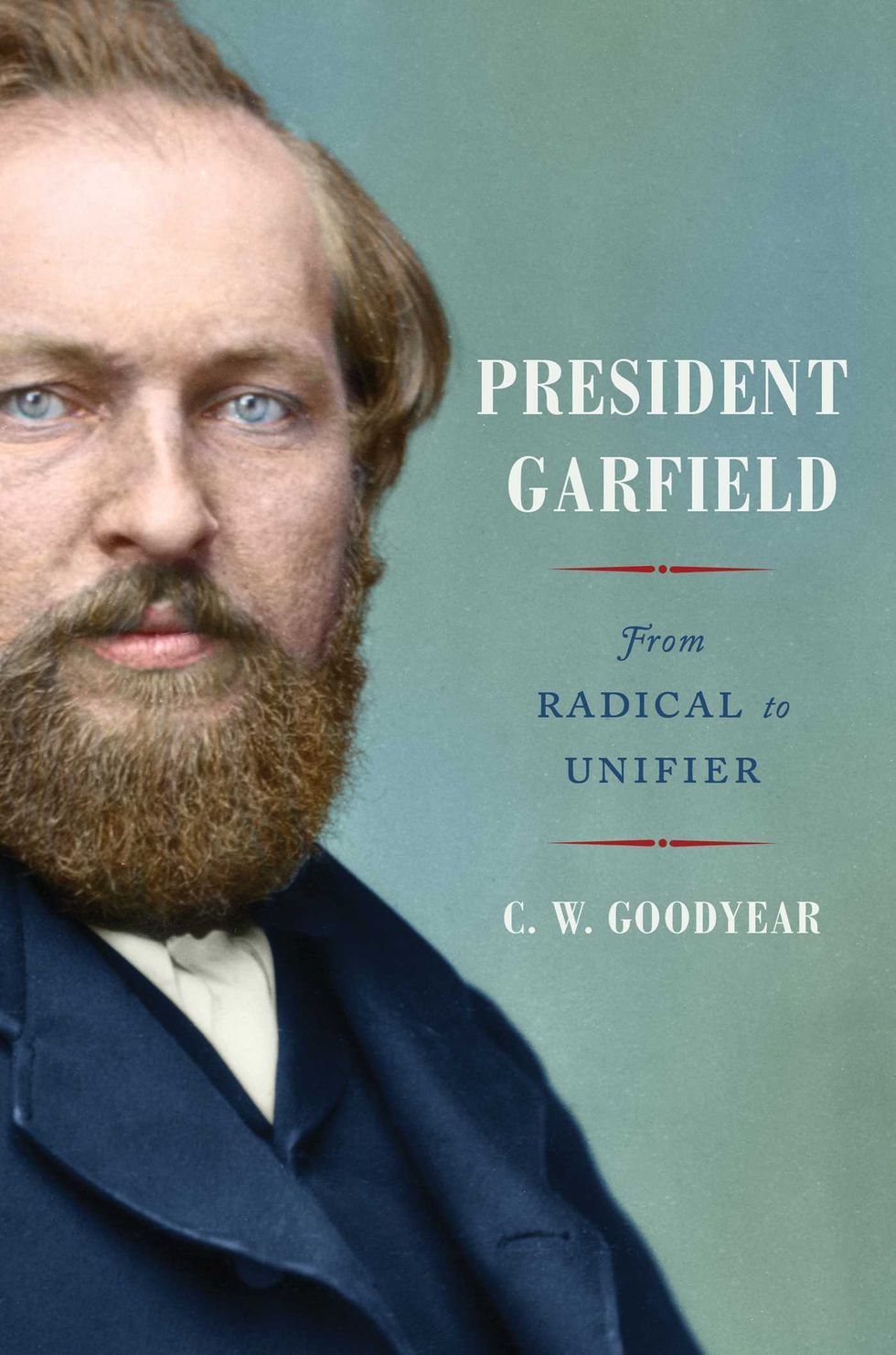

All of this brings me to James Garfield, our twentieth president. His claim to fame is that he was assassinated, joining a morbid fraternity with Lincoln and JFK, only six months into office. But who was Garfield, otherwise? And what did he do? Do I see a show of hands? Not many — including me. Thanks to a new biography, however, by C. W. Goodyear, “James Garfield: From Radical to Unifier,” I’ve been enlightened. In this comprehensive and well-researched tome from Simon & Schuster, Goodyear makes a strong case for reviving the Ohioan’s legacy beyond the split-second moment in 1878 when he was gunned down at the Potomac Railroad Station in Washington, D.C., Garfield emerges as one of our country’s greatest statesman and one of our most intelligent.

Employing largely primary sources and well-chosen quotes, Goodyear takes us from Garfield’s humble beginnings as a dirt poor “log cabin president,” to a canal boatman, Williams College graduate, Civil War veteran, long-time member of the House, and finally chief executive in the Republican party. Given Garfield’s brief tenure as president, the years as a Congressman are naturally given more attention. At first blush, this might seem like a hard sell to a prospective reader. Passing legislative bills, debating in the House and Ways Committee, and arguing for bipartisan policies, seem about as scintillating as a trip to the dentist. But Goodyear makes us think otherwise. He presents Garfield as a towering man of ideas, whose fervent beliefs on racial equality and education reform, among others, make him a man ahead of his time and a true activist.

His stance against slavery was not merely a political one, but a genuinely heartfelt one. There are moving passages in the book revealing Garfield’s passionate belief in the plight of Black Americans who were still struggling to achieve basic freedoms fifteen years after Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. “To violate the sanctity of suffrage is more than an evil,” Garfield stays in one address, “it is a crime…”

In contrast, Woodrow Wilson, more than a generation later, was much more regressive, segregating Federal offices, including the Navy, the Commerce and Treasury Department.

To some of his contemporaries, Garfield appeared less ideological and more opportunistic, following the prevailing winds of political expediency more than any idealistic stance. Frederick Douglas for one, as Goodyear notes, felt he lacked backbone. Other adversaries chafed at his appeasements to further his party’s agenda. But over the course of his career, it becomes clear in this book that Garfield earned the respect and often reverence of his colleagues — and Americans at large — as a fair-minded person, who could see both sides of an issue and was willing to change his mind if he felt genuinely convinced. A rarity today in politics.

Goodyear is to be applauded for his thorough history, given that he has much less precedent to work with than other authors of more popular subjects. Garfield has not exactly been a subject of many best-sellers, and far fewer books have been published about him than, say Lincoln, who seems to have a book published about him every month.

Goodyear’s’ prose is articulate and measured, and he does not slip into hagiography, which is the bane of lesser biographers. My only issue is that he dwells too long on the intricacies — and intimacies — of the slow, agonizing deathwatch of the bedridden Garfield ( who survived for three months after he was shot), describing in exhaustive detail the doctor’s reports on his bowel movements, his “resurging parotid gland,” his “boils the size of peas,” and the “pus leaking into his ear canal.” These bits, to my mind, add little to our understanding of Garfield, other than that he was a stoic figure to the end.

To Goodyear’s credit, he makes clever use of Shakespeare quotes, which open each chapter and act as pithy prologues to the ensuing text. The Bard’s passages are especially interesting because they are taken from Garfield’s diaries, to inspire him, and show what a thoughtful figure Garfield was. It makes us wonder what kind of president he might have been, given the chance. For the moment, we are left to our imagination, and the pages of Goodyear’s biography, to ponder this largely forgotten, yet exceptional man.

C.W. Goodyear will discuss his book, “President Garfield,” at House of Books in Kent, Conn., on Saturday, July 22, at 6 p.m.

Simon & Schuster

Wes Allyn breaks away from the St. Paul defense for a reception touchdown Wednesday, Nov. 26.

BRISTOL — The Gilbert/Northwestern/Housatonic co-op football team ended the season with a 34-0 shutout victory over St. Paul Catholic High School Wednesday, Nov. 26.

It was GNH’s fourth consecutive Turkey Bowl win against St. Paul and the final game for 19 GNH seniors.

The Yellowjacket defense played lights out, holding St. Paul’s offense to 73 total yards and forcing three turnovers. Owen Riemer and Tyler Roberts each caught an interception and Jacob Robles recovered a fumble.

QB Trevor Campbell threw for three touchdowns: one to Wes Allyn, one to Cole Linnen and one to Esten Ryan. GNH scored twice on the ground with rushing touchdowns from Linnen and Riemer.

The game concluded in some confusion. A late run by Linnen ended when he was tackled near the end zone. The ball was spotted at the one-yard line and GNH took a knee to end the fourth quarter with the scoreboard reading 28-0. After the game, Linnen’s run was reassessed as a touchdown, and the final score was adjusted to 34-0.

Coach Scott Salius was thankful that his team went out on a high note. “We’re one of the few teams in the state that will finish with a win.” He commented on the “chippiness” of this year’s Thanksgiving matchup. “We have started a true rivalry.”

GNH won four of the last five games and ended with a record of 5-5.

“Battling back from 1-4, huge turnaround. I couldn’t be happier,” said GNH captain Wes Allyn after the win. “Out of the four years I’ve been playing, undefeated on Thanksgiving. No one will ever take that away from me.”

Looking back on his final varsity season, Nick Crodelle said he will remember “practice, complaining about practice, and getting ready for the games. Game day was a lot of fun.”

Hunter Conklin said ending on a win “feels great” and appreciated his time on the field with his teammates. “There’s no one else I’d rather do it with.”

“I’m so thankful to have these guys in my life,” said Riemer. “It’s emotional.”

“Once Upon a Time in America” features ten portraits by artist Katro Storm.

The Kearcher-Monsell Gallery at Housatonic Valley Regional High School in Falls Village is once again host to a wonderful student-curated exhibition. “Once Upon a Time in America,” ten portraits by New Haven artist Katro Storm, opened on Nov. 20 and will run through the end of the year.

“This is our first show of the year,” said senior student Alex Wilbur, the current head intern who oversees the student-run gallery. “I inherited the position last year from Elinor Wolgemuth. It’s been really amazing to take charge and see this through.”

Part of what became a capstone project for Wolgemuth, she left behind a comprehensive guide to help future student interns manage the gallery effectively. “Everything from who we should contact, the steps to take for everything, our donors,” Wilbur said. “It’s really extensive and it’s been a huge help.”

Art teacher Lilly Rand Barnett first met Storm a few years ago through his ICEHOUSE Project Space exhibition in Sharon, “Will It Grow in Sharon?” in which he planted cotton and tobacco as part of an exploration of ancestral heritage.

“And the plants did grow,” said Barnett. She asked Storm if her students could use them, and the resulting work became a project for that year’s Troutbeck Symposium, the annual student-led event in Amenia that uncovers little-known or under-told histories of marginalized communities, particularly BIPOC histories.

Last spring, Rand emailed to ask if Storm would consider a solo show at HVRHS. He agreed.

And just a few weeks ago, he arrived — paints, brushes and canvases in tow.

“When Katro came to start hanging everything, he took up a mini art residency in Ms. Rand’s room,” Wilbur said. “All her students were able to see his process and talk to him. It was great working with him.”

Perhaps more unexpected was his openness. “He really trusted us as curators and visionaries,” Wilbur said. “He said, ‘Do with it what you will.’”

Storm’s artistic training began at New Haven’s Educational Center for the Arts. His talent earned him a full scholarship to the Arts Institute of Boston, then Boston’s Museum School, where he painted seven oversized portraits of influential Black figures — in seven days — for his final project. Those works became the backbone of his early exhibitions, including at Howard University’s National Council for the Arts.

Storm has created several community murals like the 2009 READ Mural featuring local heroes, and several literacy and wellness murals at the Stetson Branch Library in New Haven. Today, he teaches and works, he said, “wherever I set up shop. Sometimes I go outside. Sometimes I’m on top of roofs. Wherever it is, I get the job done.”

His deep ties to education made a high school gallery an especially meaningful stop. “No one really knew who these people were except maybe John Lennon,” Storm said of the portraits in the show. “It’s really important for them to know James Baldwin and Shirley Chisholm. And now they do.”

The exhibition includes a wide list of subjects: James Baldwin, Shirley Chisholm, Redd Foxx, Jasper Johns, Marilyn Manson, William F. Buckley, Harold Hunter, John Lennon, as well as two deeply personal works — a portrait of Tracy Sherrod (“She’s a friend of mine… She had an interesting hairdo”) and a tribute to his late friend Nes Rivera. “Most of the time I choose my subjects because there are things I want to see,” Storm said.

Storm’s paintings, which he describes as “full frontal figuratism,” rely on drips, tonal shifts, and what feels like emerging depth. His process moves quickly. “It depends on how fast it needs to get done,” he said. “Sometimes I like to take the long way up the mountain. Instead of doing an outline, I just start coloring, blocking things off with light and dark until it starts to take shape.”

He’s currently in a black-and-white phase. “Right now, I’m inspired by black and white, the way I can really get contrast and depth.”

Work happens on multiple canvases at once. “Sometimes I’ll have five paintings going on at one time because I go through different moods, and then there’s the way the light hits,” he said. “It’s kind of like cooking. You’ve got a couple things going at once, a couple things cooking, and you just try to reach that deadline.”

For Wilbur, who has studied studio arts “ever since I was really young” and recently applied early decision to Vassar, the experience has been transformative. For Storm — an artist who built an early career painting seven portraits in seven days and has turned New York’s subway corridors into a makeshift museum — it has been another chance to merge artmaking with education, and to pass a torch to a new generation of curators.

Le Petit Ranch offers animal-assisted therapy and learning programs for children and seniors in Sheffield.

Le Petit Ranch, a nonprofit offering animal-assisted therapy and learning programs, opened in April at 147 Bears Den Road in Sheffield. Founded by Marjorie Borreda, the center provides programs for children, families and seniors using miniature horses, rescued greyhounds, guinea pigs and chickens.

Borreda, who moved to Sheffield with her husband, Mitch Moulton, and their two children to be closer to his family, has transformed her longtime love of animals into her career. She completed certifications in animal-assisted therapy and coaching in 2023, along with coursework in psychiatry, psychology, literacy and veterinary skills.

Le Petit Ranch operates out of two small structures next to the family’s home: a one-room schoolhouse for animal-assisted learning sessions and a compact stable for the three miniature horses, Mini Mac, Rocket and Miso. Other partner animals include two rescued Spanish greyhounds, Yayi and Ronya; four guinea pigs and a flock of chickens.

Borreda offers programs at the Scoville Library in Salisbury, at Salisbury Central School and surrounding towns to support those who benefit from non-traditional learning environments.

“Animal-assisted education partners with animals to support learning in math, reading, writing, language and physical education,” she said. One activity, equimotricité, has children lead miniature horses through obstacle courses to build autonomy, confidence and motor skills.

She also brings her greyhounds into schools for a “min vet clinic,” a workshop that turns lessons on dog biology and measuring skills into hands-on, movement-based learning. A separate dog-bite prevention workshop teaches children how to read canine body language and respond calmly.

Parents and teachers report strong results. More than 90% of parents observed greater empathy, reduced anxiety, increased self-confidence and improved communication and cooperation in their children, and every parent said animal-assisted education made school more enjoyable — with many calling it “the highlight of their week.”

Le Petit Ranch also serves seniors, including nursing home residents experiencing depression, social withdrawal or reduced physical activity. Weekly small-group sessions with animals can stimulate cognitive function and improve motor skills, balance and mobility.

Families can visit Le Petit Ranch for animal- assisted afterschool sessions, Frech immersion or family walks. She also offers programs for schools, libraries, community centers, churches, senior centers and nursing homes.

For more information, email info@lepetitranch.com, visit lepetitranch.com, follow @le.petit.ranch on Instagram or call 413-200-8081.