Latest News

Sharon Center School

File photo

SHARON — A Sharon Center School staff member discovered a “facsimile firearm” behind a file cabinet around 2 p.m. Wednesday, Dec. 10, prompting an immediate response from State Police and a same-day notification to parents, according to police officials and an email obtained by The Lakeville Journal.

Melony Brady-Shanley, the Region One Superintendent, wrote in the email that, upon the item’s discovery, “The State Police were immediately notified and responded to the building.”

A canine team was brought in to sweep the building to confirm no additional items were present, “and the building has been fully cleared. The State Police consider this an isolated incident and not criminal in nature,” Brady-Shanley wrote.

State Police explained, “Troopers from Troop B - North Canaan were dispatched to the Sharon Center School for reports of a firearm located in a closet. The firearm was determined to be a non-firing, replica firearm... There was no threat to the school or the public.”

Brady-Shanley emphasized in the e-mail that “the safety and well-being of our students and staff remain our highest priority at all times. We will continue to follow and strengthen our safety protocols to ensure that our schools remain secure, supportive environments for learning.”

Keep ReadingShow less

Our visit to Hancock Shaker Village

Dec 10, 2025

The Stone Round Barn at Hancock Shaker Village.

Jennifer Almquist

My husband Tom, our friend Jim Jasper and I spent the day at Hancock Shaker Village in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. A cold, blustery wind shook the limbs of an ancient apple tree still clinging to golden fruit. Spitting sleet drove us inside for warmth, and the lusty smells of manure from the goats, sheep, pigs and chickens in the Stone Round Barn filled our senses. We traveled back in time down sparse hallways lined with endless peg racks. The winter light was slightly crooked through the panes of old glass. The quiet life of the Shakers is preserved simply.

Originally founded in England, the Shakers brought their communal religious society to the New World 250 years ago. They sought the perfection of heaven on earth through their values of equality and pacifism. They followed strict protocols of behavior and belief. They were celibate and never married, yet they loved singing and ecstatic dancing, or “shaking,” and often adopted orphans. To achieve their millennialist goal of transcendental rapture, we learned, even their bedclothes had to conform: One must sleep in a bed painted deep green with blue and white coverings.

Shakers believed in gender and racial equality and anointed their visionary founding leader, Mother Ann Lee, an illiterate yet wise woman, as the Second Coming. They embraced sustainability and created practical designs of great utility and beauty, such as the mail-order seed packet, the wood stove, the circular saw, the metal pen, the flat broom and wooden clothespins.

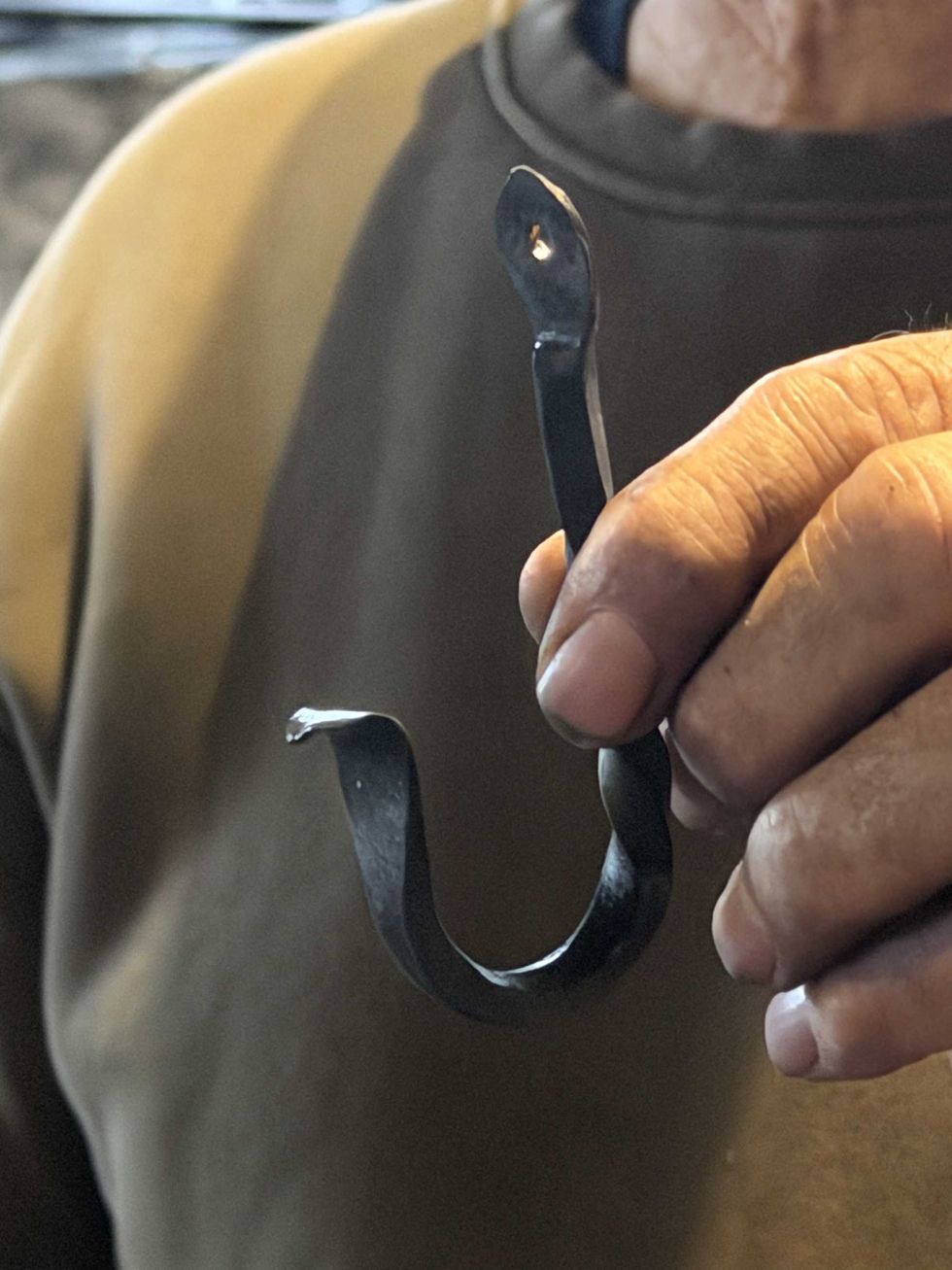

Burning coal smelled acrid as the blacksmith fired up his stove to heat the metal rod he was transforming into a hook. Hammer on anvil is an ancient sound. My husband has blacksmithing skills and once made the strap hinges and thumb latches for a friend’s home.

Shaker chairs and rockers are still made today in the woodworker’s shop. They are well made and functional, with woven cloth or rush seats. In the communal living space, or Brick Dwelling, chairs hang from the Shaker pegs that run the length of the hallways, which once housed more than 100 Shakers.

In 1826, the 95-foot Round Stone Barn was built of limestone quarried from the land of the 3,000-acre Hancock Shaker Village. Its unique design allowed a continuous workflow. Fifty cows could stand in a circle facing one another and be fed more easily. Manure could be shoveled into a pit below and removed by wagon and there was more light and better ventilation.

Shakers called us the “people of the world” and referred to their farm as the City of Peace. We take lessons away with us, yearning somehow for their simplicity and close relationship to nature. One Shaker said, “There’s as much reverence in pulling an onion as there is in singing hallelujah.”

A sense of calm came over me as I looked across the fields to the hills in the distance. A woman like me once stood between these long rows of herbs — summer savory, sage, sweet marjoram and thyme — leaned on her shovel brushing her hair back from her eyes, watching gray snow clouds roll down the Berkshires.

More information at hancockshakervillage.org

Keep ReadingShow less

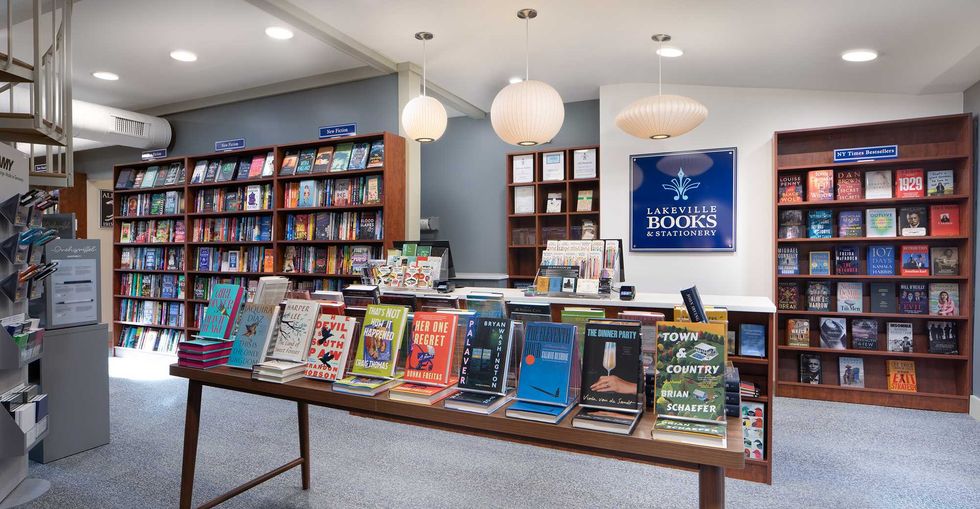

Exterior of Lakeville Books & Stationery in Great Barrington.

Provided

Fresh off the successful opening of Lakeville Books & Stationery in April 2025, Lakeville residents Darryl and Anne Peck have expanded their business by opening their second store in the former Bookloft space at 63 State St. (Route 7) in Great Barrington.

“We have been part of the community since 1990,” said Darryl Peck. “The addition of Great Barrington, a town I have been visiting since I was a kid, is special. And obviously we are thrilled to ensure that Great Barrington once again has a new bookstore.”

The second Lakeville Books & Stationery is slightly larger than the first store. It offers more than 10,000 books and follows the same model: a general-interest store with a curated mix of current bestsellers, children’s and young readers’ sections; and robust collections for adults ranging from arts and architecture, cooking and gardening, and home design to literature and memoirs. Anne reads more than 150 new titles every year (as many as a Booker Prize judge) and is a great resource to help customers find the perfect pick.

A real-time inventory system helps the store track what’s on hand, and staff can order items that aren’t currently available. There is also a selection of writing and paper goods, including notecards, journals, pens and notebooks, as well as art supplies, board games, jigsaw puzzles and more. The owners scour the stationery trade shows twice a year and, Darryl says, “like to tailor what we offer to suit the interest of our customers in each market.”

The Pecks know what it takes to run a successful local enterprise. Darryl has a 53-year background in retail and has launched several successful businesses. He and Anne owned and operated a bookstore on St. Simons Island, Georgia, from 2019 to 2025. They are tapping into their local roots with both stores. They raised their family in Sharon, and their daughter Alice, a native of the Northwest Corner, manages the Lakeville store.

The family values the role that a retail store plays as a supporting partner in the community, and they prioritize great management in both locations, hiring and training talent from local communities. Their 10 team members across both stores are from the area, and two of the Great Barrington employees previously worked at Bookloft.

Darryl and Anne’s attention to customer service is everywhere apparent and adds to the enjoyable and irreplaceable in-store shopping experience. The books are in pristine condition, eliminating the risk of damage that sometimes occurs during shipping. This is especially important for books that will live on people’s shelves and coffee tables for years.

Darryl says, “People love the in-store discovery — you find books you didn’t know existed, which is very difficult to do on a website. Also, many customers depend on our recommendations when visiting. There is a saying about bookstores versus online ordering: We may not have exactly what you were looking for, but we have what you want.”

Lakeville Books & Stationery’s Great Barrington store is open 7 days a week, Monday-Saturday, 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., and Sunday, 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Parking is available in the lot behind the building and in the parking lot behind the firehouse. The entrance to the store is accessible from the store parking lot.

For more information, go to lakevillebooks.com., and sign-up for the Lakeville Books newsletter.

Richard Feiner and Annette Stover have worked and taught in the arts, communications, and philanthropy in Berlin, Paris, Tokyo and New York. Passionate supporters of the arts, they live in Salisbury and Greenwich Village.

Keep ReadingShow less

loading