Latest News

Love is in the atmosphere

Apr 24, 2024

Author Anne Lamott

Sam Lamott

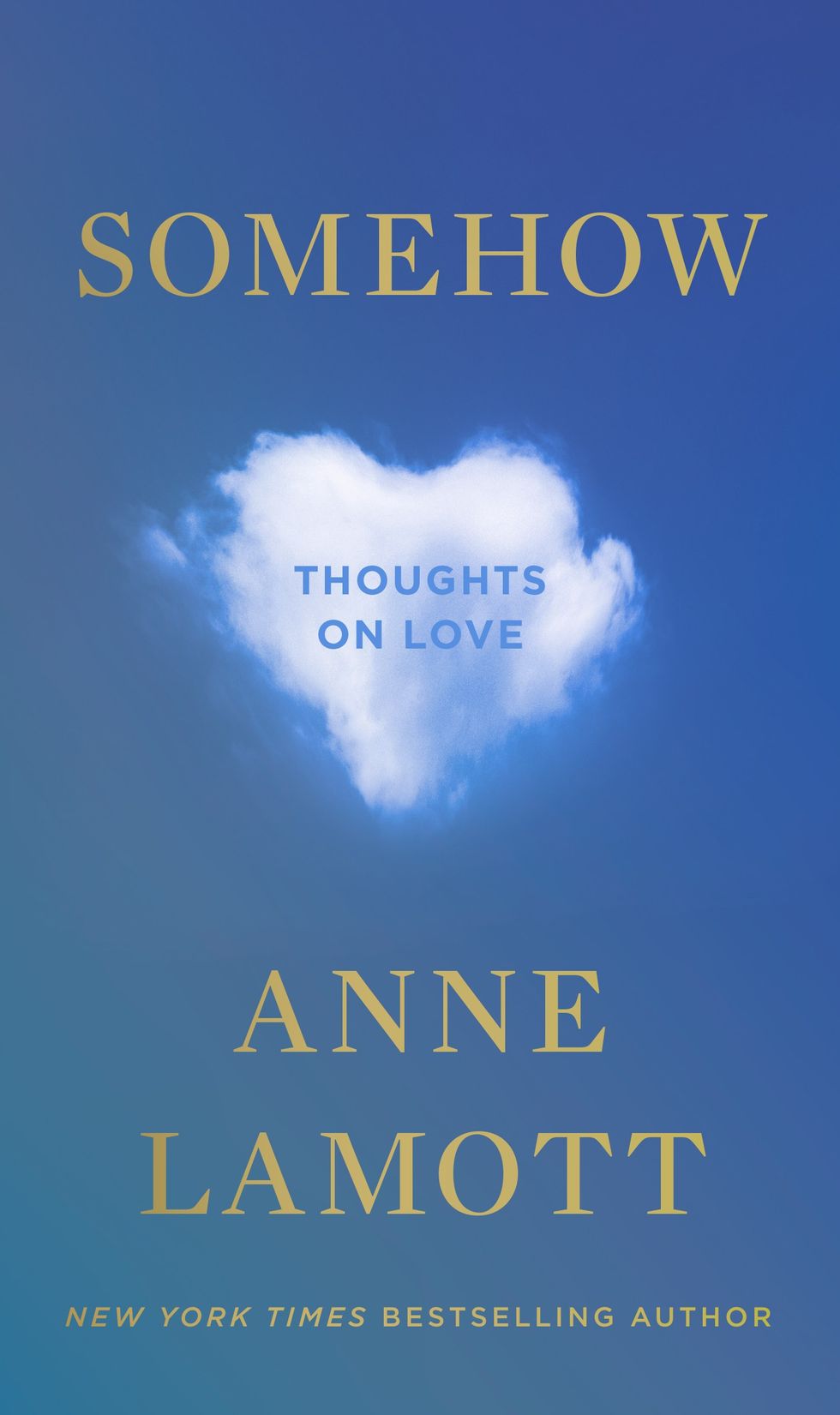

On Tuesday, April 9, The Bardavon 1869 Opera House in Poughkeepsie was the setting for a talk between Elizabeth Lesser and Anne Lamott, with the focus on Lamott’s newest book, “Somehow: Thoughts on Love.”

A best-selling novelist, Lamott shared her thoughts about the book, about life’s learning experiences, as well as laughs with the audience. Lesser, an author and co-founder of the Omega Institute in Rhinebeck, interviewed Lamott in a conversation-like setting that allowed watchers to feel as if they were chatting with her over a coffee table.

“I feel like I’m in my living room talking with my closest friends,” Lamott said.

In her 20th book, “Somehow: Thoughts on Love,” she goes back in time, writing about her own personal life experiences in a candid way, about her family, recovery and her faith. Lamott relates coming face to face with intense emotions and multiple epiphanies and lessons she’s learned.

The book explores the transformative power that love has in our lives: how it surprises us, forces us to confront uncomfortable truths, reminds us of our humanity, and guides us forward.

“Love just won’t be pinned down,” she says. “It is in our very atmosphere and lies at the heart of who we are."

“We are creatures of love,” she writes on her website describing the premise of the book.

Lamott is a progressive writer. She married for the first time at the age of 65, and has been sober for 37 years. She shares a life with her husband, Neal Allen, who is also a writer, her son Sam Lamott, and her grandson. Her family makes up the main characters throughout the book, reminiscing on escapades together.

“To have a heavy-hitting writer here is just wonderful, I have been following her since San Francisco, and when I heard she was in Poughkeepsie I bought tickets right away,” said Lamott fan Suzanne Sagan.

The Bardavon audience was filled with women from the ages of 34-70, some were able to convince their husbands to tag along and listen to the conversation. All attentive to her, laughing at the jokes and even attempting to sing her happy birthday.

Conversation topics ranged from the themes in her book, to sobriety, to telling stories about being a mother.

Learning about how to help yourself first, if you want to feel the love you have to spread the love, aging, relationships, having your cup filled full with your own water, and learning from your mistakes.

“That’s what life is like, slipping on a cosmic banana,” Lamott declared.

“As with all of her deceivingly simply rendered pieces, Lamott’s foibles are central to the 12 stories told here. Reconciling her own flaws as the key to tolerance is implied. Falling short is a given, especially when seeking to understand folks whose views are different from hers, particularly when they’re on the political spectrum. But demonstrating love to those who cause harm just might be too much of a reach for her — that stuff is for saints; it’s next-level wellness. Yet, Lamott strives,” Denise Sullivan writes for Datebook, a San Francisco Arts and Entertainment Guide.

Lamott was able to quote well known names such as Susan B. Anthony, Carrie Fisher, and Mother Theresa. During the conversation, she often turned to quotes that helped her create the mindset she has today, and spreads to the audience.

The talk was presented by Oblong Books in partnership with Bardavon Presents.

Keep ReadingShow less

Oscar Lock, a Hotchkiss senior, got pointers and encouragement from Tim Hunter, stewardship director of The Sharon Land Trust, while sawing buckthorn.

John Coston

It was a ramble through bramble on Wednesday, April 17 as a handful of Hotchkiss students armed with loppers attacked a thicket of buckthorn and bittersweet at the Sharon Land Trust’s Hamlin Preserve.

The students learned about the destructive impact of invasives as they trudged — often bent over — across wet ground on the semblance of a trail, led by Tom Zetterstrom, a North Canaan tree preservationist and member of the Sharon Land Trust.

The return of students on this working walkthrough was part of Hotchkiss’s Fairfield Farm Ecosystem and Adventure Team, a program that incorporates environmental stewardship in the learning experience.

The Hamlin Preserve is a 210-acre property with 2.5 miles of trails, and the Hamlin conifer grove restoration is a large-scale landscape forest preservation project.

The group entered at the end of Stone House Road and proceeded into an invasive thicket that has already taken its toll on cedars and pines. Zetterstrom stopped the group for several lecture moments and demonstrations of the proper way to cut bittersweet.

Tim Hunter, stewardship director of the Trust, pulled out a folding handsaw that student Oscar Lock, a senior, used to sever a buckthorn at ground level.

Shaye Lee, a sophomore, took a turn with the saw on some privet.

As the group huddled under a close canopy of invasive vegetation that was overtaking everything in sight, Zetterstrom explained that invasive-laden patch was once productive farmland.

As the two-hour stroll-and-lop ended, the group assembled in a hay field on the property to observe a healthy American elm at the edge of the open field that has been saved by the Trust’s efforts.

Pointing to Red Mountain in the short distance, Zetterstrom told the students: “When you come back for your reunions — maybe in 50 years — you can say I helped save those trees.”

Keep ReadingShow less

loading