Latest News

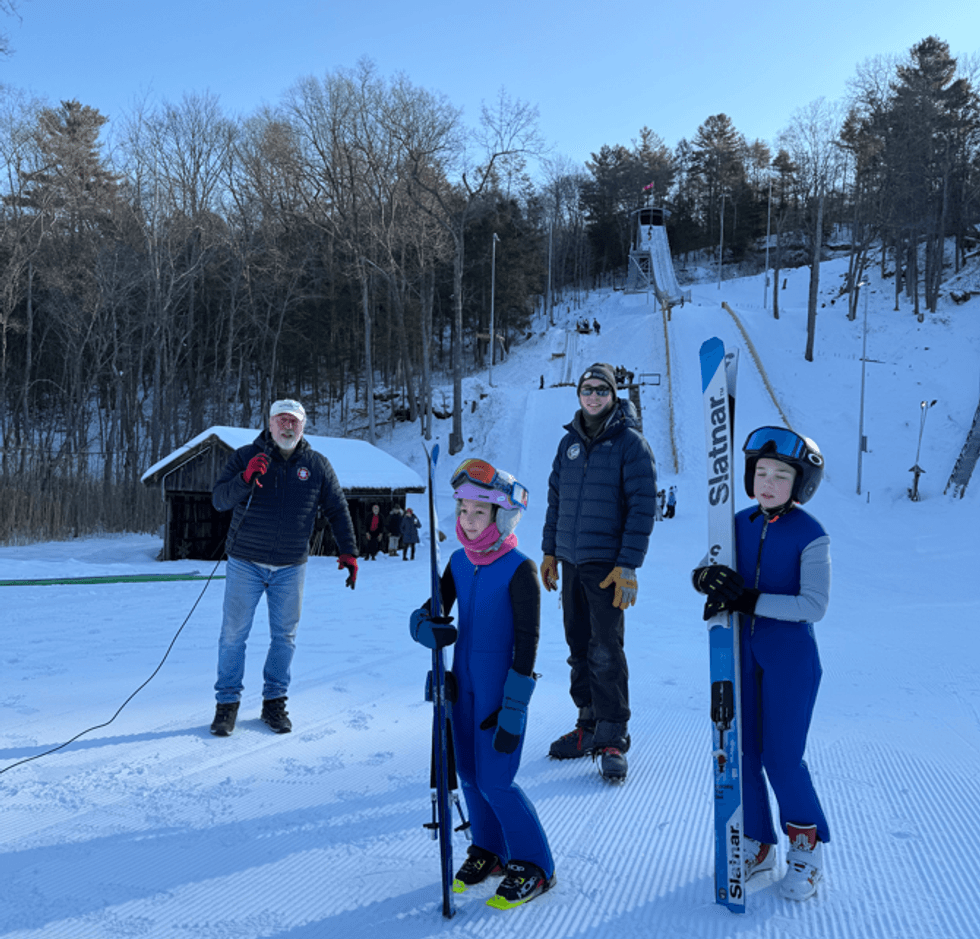

Gus Tripler prepares to jump from the new 36-meter jump.

Margaret Banker

SALISBURY - With the Winter Olympics just weeks away, Olympic dreams felt a little closer to home for Salisbury Central School students on Feb. 4, when student ski jumpers from the Salisbury Winter Sports Association put on a live demonstration at the Satre Hill Ski Jumping Complex for more than 300 classmates and teachers.

With screams of delight, student-athletes soared through the air, showcasing years of training and focus for an audience of their peers. The atmosphere was electric as the jumpers soaked up the attention like local celebrities.

Satre Hill and SWSA are celebrating their 100th Anniversary of ski jumping in northwest Connecticut this week. As part of this week’s festivities, Salisbury Central School was invited to watch a demonstration of jumping on the 20-meter and the newly installed 36-meter ski jumps.

The event began with Coach Seth Gardner welcoming Salisbury Central School to the jump complex and explaining the sport and training that goes into ski jumping.

Ski jumpers Oona Mascavage and Camden Hubbard assisted Coach Gardner by showing off equipment used in the sport from the oversized skis to the aerodynamic jump suits as well as the proper starting form known as the in-run position.

Then, Willie Hallihan of the SWSA offered students a brief history of ski jumping in Salisbury, tracing the sport’s local roots back a century to when the Satre brothers first launched themselves off a barn before going on to construct the area’s first ski jumping hill. After the history lesson, younger jumpers showed how to begin the sport by skiing down the landing portion of the hill called the outrun.

Jumpers proceeded to show basic jumping from the 20-meter hill, where most beginners start. The event was capped with a demonstration of jumping from the bigger 36-meter hill, where the real flying begins led by one of SWSA's veterans, Gus Tripler.

The SWSA operates one of the oldest ski jumping facilities in the United States and is the home club of 1956 Olympic ski jumper Roy Sherwood and legendary ski jumping coach Larry Stone. The organization has hosted Olympic ski jumpers over the years, including many members of the current U.S. Olympic ski jumping team, now competing in Italy at the Winter Games.

The future of ski jumping at SWSA remains strong, with plans underway to install artificial grass that would allow for summer jumping and year-round training. Islay Sheil, a homegrown jumper, is currently competing on the Junior National Ski Jumping circuit, which includes Olympic-size 100-meter hills.

The 100th anniversary celebrations will continue Feb. 6–8 with Jumpfest, which will feature ski jumping events at Satre Hill in Salisbury.

Keep ReadingShow less

Classifieds - February 5, 2026

Feb 04, 2026

Help Wanted

PART-TIME CARE-GIVER NEEDED: possibly LIVE-IN. Bright private STUDIO on 10 acres. Queen Bed, En-Suite Bathroom, Kitchenette & Garage. SHARON 407-620-7777.

The Scoville Memorial Library: is seeking an experienced Development Coordinator to provide high-level support for our fundraising initiatives on a contract basis. This contractor will play a critical role in donor stewardship, database management, and the execution of seasonal appeals and events. The role is ideal for someone who is deeply connected to the local community and skilled at building authentic relationships that lead to meaningful support. For a full description of the role and to submit a letter of interest and resume, contact Library Director Karin Goodell, kgoodell@scovillelibrary.org.

Weatogue Stables in Salisbury, CT: has an opening for experienced barn help for Mondays and Tuesdays. More hours available if desired. Reliable and experienced please! All daily aspects of farm care- feeding, grooming, turnout/in, stall/barn/pasture cleaning. Possible housing available for a full-time applicant. Lovely facility, great staff and horses! Contact Bobbi at 860-307-8531. Text best for prompt reply.

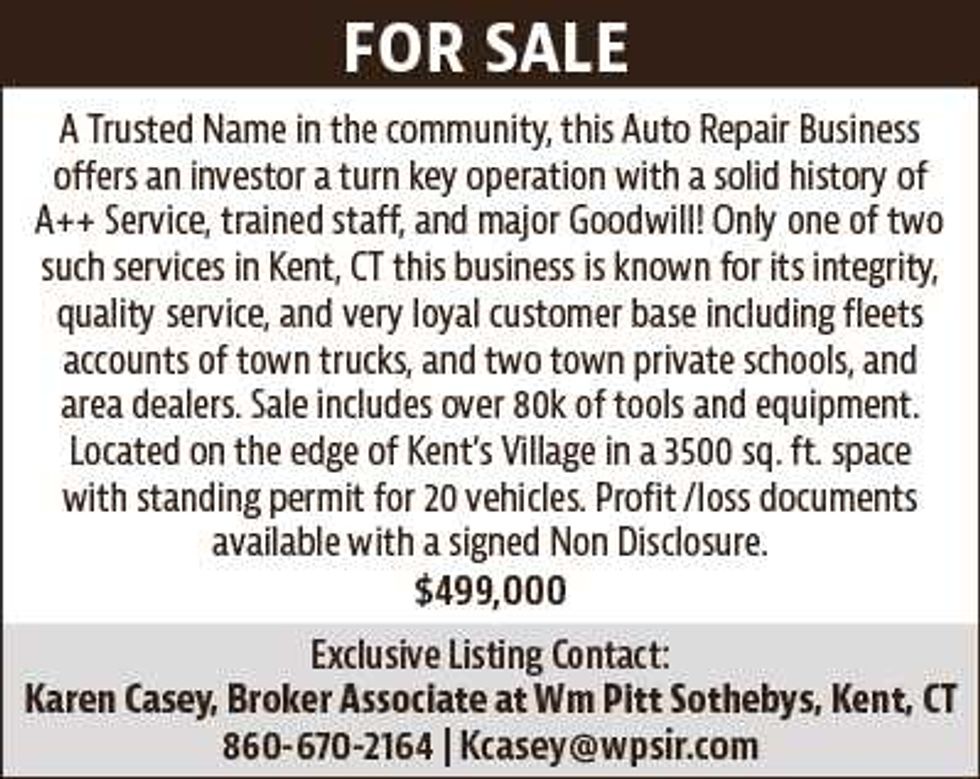

Services Offered

COLBYS TREE SERVICES: provides reliable tree removal, trimming, and storm cleanup. Locally owned and fully insured, we’re committed to safe work, honest service, and keeping your property looking its best. CALL/TEXT 860-248-9456.

Hector Pacay Landscaping and Construction LLC: Fully insured. Renovation, decking, painting; interior exterior, mowing lawn, garden, stone wall, patio, tree work, clean gutters, mowing fields. 845-636-3212.

PROFESSIONAL HOUSEKEEPING & HOUSE SITTING: Experienced, dependable, and respectful of your home. Excellent references. Reasonable prices. Flexible scheduling available. Residential/ commercial. Call/Text: 860-318-5385. Ana Mazo.

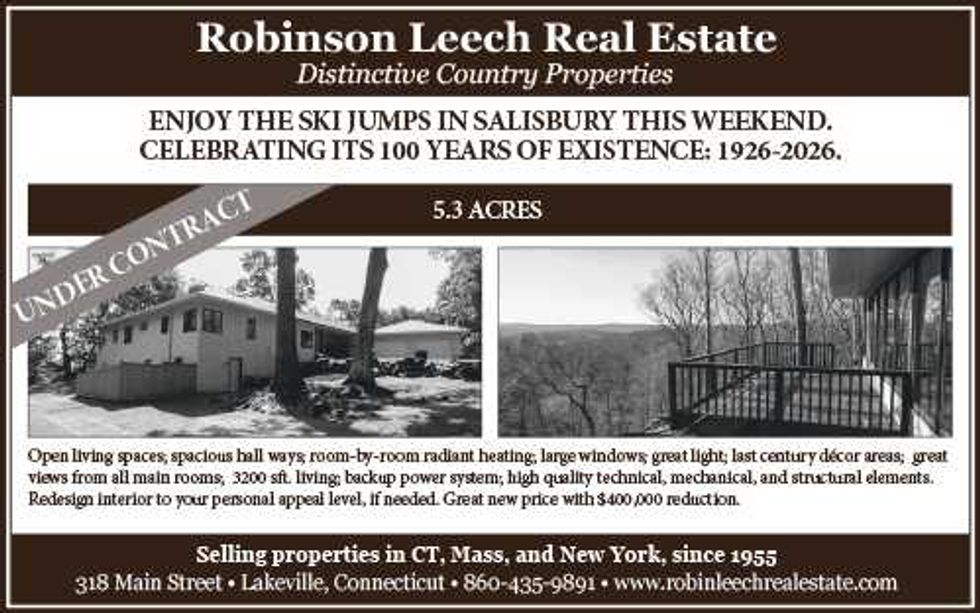

Real Estate

PUBLISHER’S NOTICE: Equal Housing Opportunity. All real estate advertised in this newspaper is subject to the Federal Fair Housing Act of 1966 revised March 12, 1989 which makes it illegal to advertise any preference, limitation, or discrimination based on race, color religion, sex, handicap or familial status or national origin or intention to make any such preference, limitation or discrimination. All residential property advertised in the State of Connecticut General Statutes 46a-64c which prohibit the making, printing or publishing or causing to be made, printed or published any notice, statement or advertisement with respect to the sale or:rental of a dwelling that indicates any preference, limitation or discrimination based on race, creed, color, national origin, ancestry, sex, marital status, age, lawful source of income, familial status, physical or mental disability or an intention to make any such preference, limitation or discrimination.

Houses For Rent

3 BR/1 BA: fully furnished/fully equipped raised ranch style home in Canaan, available February 1 to June 30. Great opportunity to experience the area! $2600/month. 860-671-8753 or contact Elyse Harney Real Estate.

Keep ReadingShow less

Legal Notices - February 5, 2026

Feb 04, 2026

Legal Notice

The Planning & Zoning Commission of the Town of Salisbury will hold a Public Hearing on Special Permit Application #2026-0307 by Amber Construction and Design Inc for vertical expansion of a nonconforming structure at 120 Wells Hill Road, Lakeville, Map 36, Lot 09 per Section 503.2 of the Salisbury Zoning Regulations. The Owners of the property are Joseph Edward Costa and Elyse Catherine Nelson. The hearing will be held on Tuesday, February 17, 2026 at 5:45 PM. There is no physical location for this meeting. This meeting will be held virtually via Zoom where interested persons can listen to & speak on the matter. The application, agenda and meeting instructions will be listed at www.salisburyct.us/agendas/. The application materials will be listed at www.salisburyct.us/planning-zoning-meeting-documents/. Written comments may be submitted to the Land Use Office, Salisbury Town Hall, 27 Main Street, P.O. Box 548, Salisbury, CT or via email to landuse@salisburyct.us. Paper copies of the agenda, meeting instructions, and application materials may be reviewed Monday through Thursday between the hours of 8:00 AM and 3:30 PM at the Land Use Office, Salisbury Town Hall, 27 Main Street, Salisbury CT.

Salisbury Planning & Zoning Commission

Robert Riva, Secretary

02-05-26

02-12-26

Notice of Agent Decision

Town of Salisbury

Inland Wetlands & Watercourses Commission

Notice is hereby given that the following action was taken by the Agent of the Inland Wetlands & Watercourses Commission of the Town of Salisbury, Connecticut on January 27, 2026:

Approved - Application IWWC-26-4 by New England Permitting, LLC for/to “Replace and reconfigure existing three-level fire escape porch and stairs for multifamily dwelling. Dimensions include: 6’ x 13’, 6’ x 12’; 6’ x 13’, 8’ x 10 ‘, 6’ x 10’; 6’ x 12’, 10’ x 8’, 6’ 12’; and 28’ x 6’.”. The property is shown on Salisbury Assessor’s map and lot 45 05 and is known as 32 MILLERTON ROAD, LAKEVILLE. The owner of the property is SALISBURY HOUSING COMMITTEE INC.

Any person may appeal such decision of such agent to the Inland Wetlands & Watercourses Commission of the Town of Salisbury within fifteen days after the publication date of this notice.

02-05-26

NOTICE OF ANNUAL TOWN MEETING

TOWN OF SALISBURY

FEBRUARY 11, 2026

7:30 P.M.

The Annual Town Meeting of the electors and citizens qualified to vote in town meetings in the Town of Salisbury, Connecticut, will be held both virtually and in person at Salisbury Town Hall, 27 Main Street, Salisbury, Connecticut, on Wednesday, February 11, 2026 at 7:30 p.m. for the following purposes:

1. To receive and act upon the report of the Town Officers and to recognize the Town Report dedication.

2. To receive and act upon the audited financial report from the Chairman of the Board of Finance and Treasurer of the Town for the fiscal year ended June 30, 2025, which is available for inspection.

3. To adopt an ordinance pursuant to which the Town will become a member town of the Northwest Regional Recovery Authority.

4. To adopt an ordinance pursuant to section 240 of Connecticut Public Act 25-168 granting a limited real property tax exemption to residents of the Town who have served in the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Coast Guard, Air Force or Space Force of the United States and have been determined by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs to have a service-connected total disability based on individual unemployability.

5. To do any other business proper to come before said meeting.

Copies of the ordinances described in items 3 and 4 above will be available for review in the Office of the Town Clerk at least seven calendar days in advance of the meeting.

The Board of Selectmen will post a notice on the Town’s website (https://www.salisburyct.us/) not less than forty-eight (48) hours prior to the Town Meeting providing instructions for the public on how to attend and provide comment or otherwise participate in the meeting.

Join the Webinar

When: Feb 11, 2026 07:30 PM Eastern Time (US and Canada)

Topic: Annual Town Meeting

Join from PC, Mac, iPad, or Android:

https://us06web.zoom.us/j/84482779679?pwd=nMp47kGr...

Webinar ID: 844 8277 9679

Passcode: 409930

Join via audio:

+1 646 558 8656 US

Dated at Salisbury, Connecticut this 16th day of January, 2026.

Curtis G. Rand,

First Selectman

Barrett Prinz,

Selectman

Katherine Kiefer, Selectman

01-29-26

02-05-26

Notice of Decision

Town of Salisbury

Inland Wetlands & Watercourses Commission

Notice is hereby given that the following action was taken by the Inland Wetlands & Watercourses Commission of the Town of Salisbury, Connecticut on January 26, 2026:

Approved - Application IWWC-25-77 by Andrew Pelletier to “Renovate existing accessory building, add foundation and decks.” The property is shown on Salisbury Assessor’s map 66 lot 28 and is known as 80 Rocky Lane, Salisbury. The owners of the property are Claudia Remley & Kevin Remley.

Approved - Application IWWC-25-79 by Dana Rohn to “Build a main house of approximately 3165 square feet with 4 bedrooms and 2.5 baths.” The property is shown on Salisbury Assessor’s map 39 lot 16 and is known as 100 Interlaken Road, Lakeville. The owners of the property are Dana & Frederick Rohn.

Any aggrieved person may appeal this decision to the Connecticut Superior Court in accordance with the provisions of Connecticut General Statutes §22a-43(a) & §8-8.

Town of Salisbury

Inland Wetlands and Watercourses Commission

Sally Spillane, Secretary

02-05-26

NOTICE TO CREDITORS

ESTATE OF

RANDALL OSOLIN

Late of Sharon

AKA Randall G. Osolin

(26-00021)

The Hon. Jordan M. Richards, Judge of the Court of Probate, District of Litchfield Hills Probate Court, by decree dated January 22, 2026, ordered that all claims must be presented to the fiduciary at the address below. Failure to promptly present any such claim may result in the loss of rights to recover on such claim.

The fiduciary is:

Karen L. Osolin

c/o Michael Downes Lynch

Law Office of Michael D. Lynch, 106 Upper Main Street, P.O. Box 1776, Sharon, CT 06069.

Megan M. Foley

Clerk

02-05-26

NOTICE TO CREDITORS

ESTATE OF SHEA CASSIDY-TETI

Late of Salisbury

(26-00018)

The Hon. Jordan M. Richards, Judge of the Court of Probate, District of Litchfield Hills Probate Court, by decree dated January 21, 2026, ordered that all claims must be presented to the fiduciary at the address below. Failure to promptly present any such claim may result in the loss of rights to recover on such claim.

The fiduciaries are:

Charles Teti and Aiden Cassidy

c/o Jeffrey Leonard Ment

The Ment Law Group, PC

225 Asylum Street

Hartford, CT 06103

Megan M. Foley

Clerk

02-05-26

TOWN OF SHARON

BOARD OF ASSESSMENT APPEALS

MARCH APPEALS

All owners of real property in the Town of Sharon are hereby warned that the Board of Assessment Appeals of the Town of Sharon will meet at the Sharon Town Hall, by appointment, in March for the purpose of hearing appeals related to the assessment of real property. All persons claiming to be aggrieved by the doings of the assessor of the Town of Sharon with regard to real property assessment on the Grand List of October 1, 2025 are hereby warned to file their appeal application to the Board of Assessment Appeals on or before Friday, February 20, 2026 at 12:00pm. Applications received after that date will be rejected. For an application, please visit www.sharonct.gov or contact Nikki Blass in the Land Use Office at (860) 364-0909, or the Assessor’s Office at (860) 364-0205.

Board of

Assessment Appeals

Chairman - Thomas F. Casey, Sr.

Sharon, Connecticut

02-05-26

Keep ReadingShow less

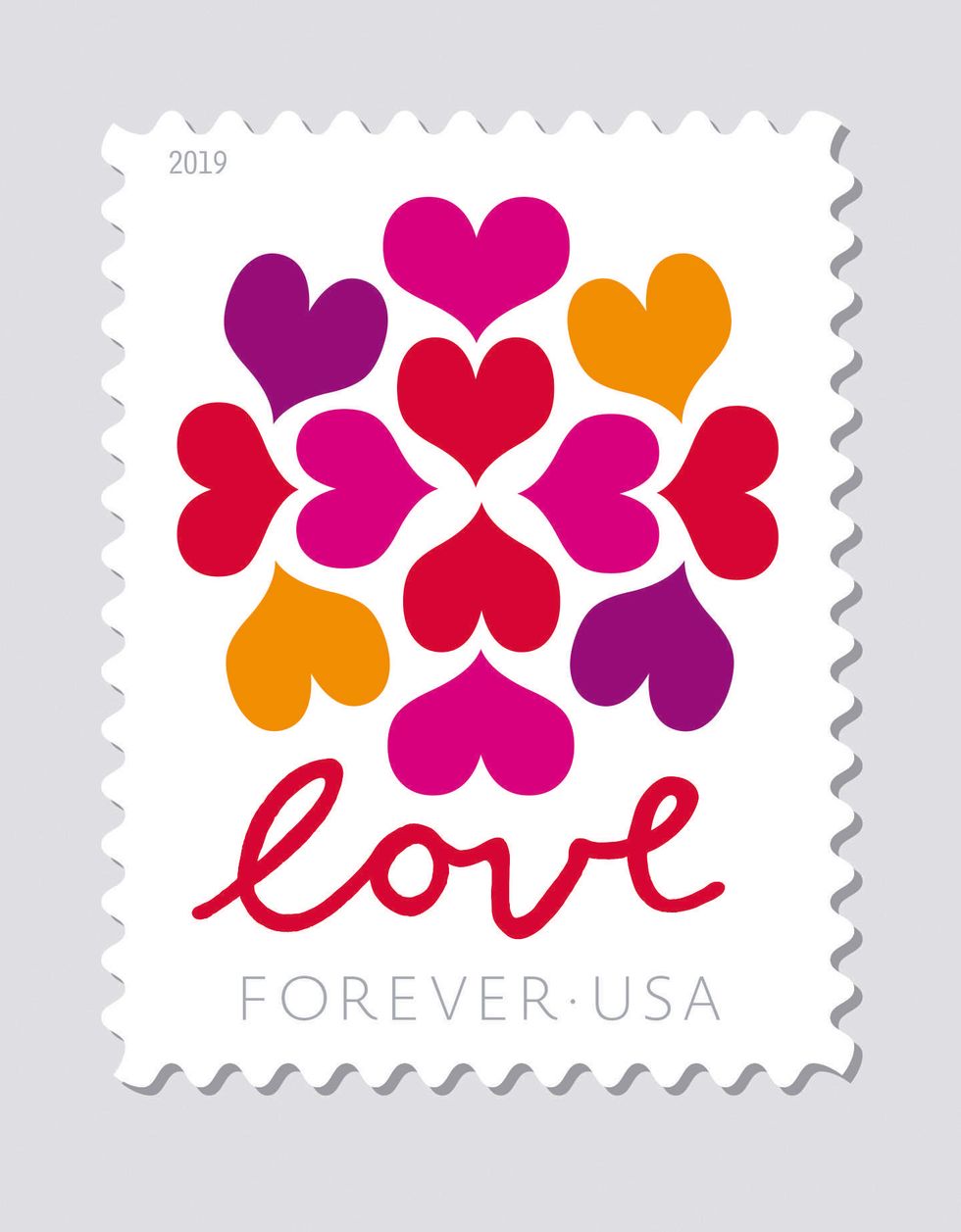

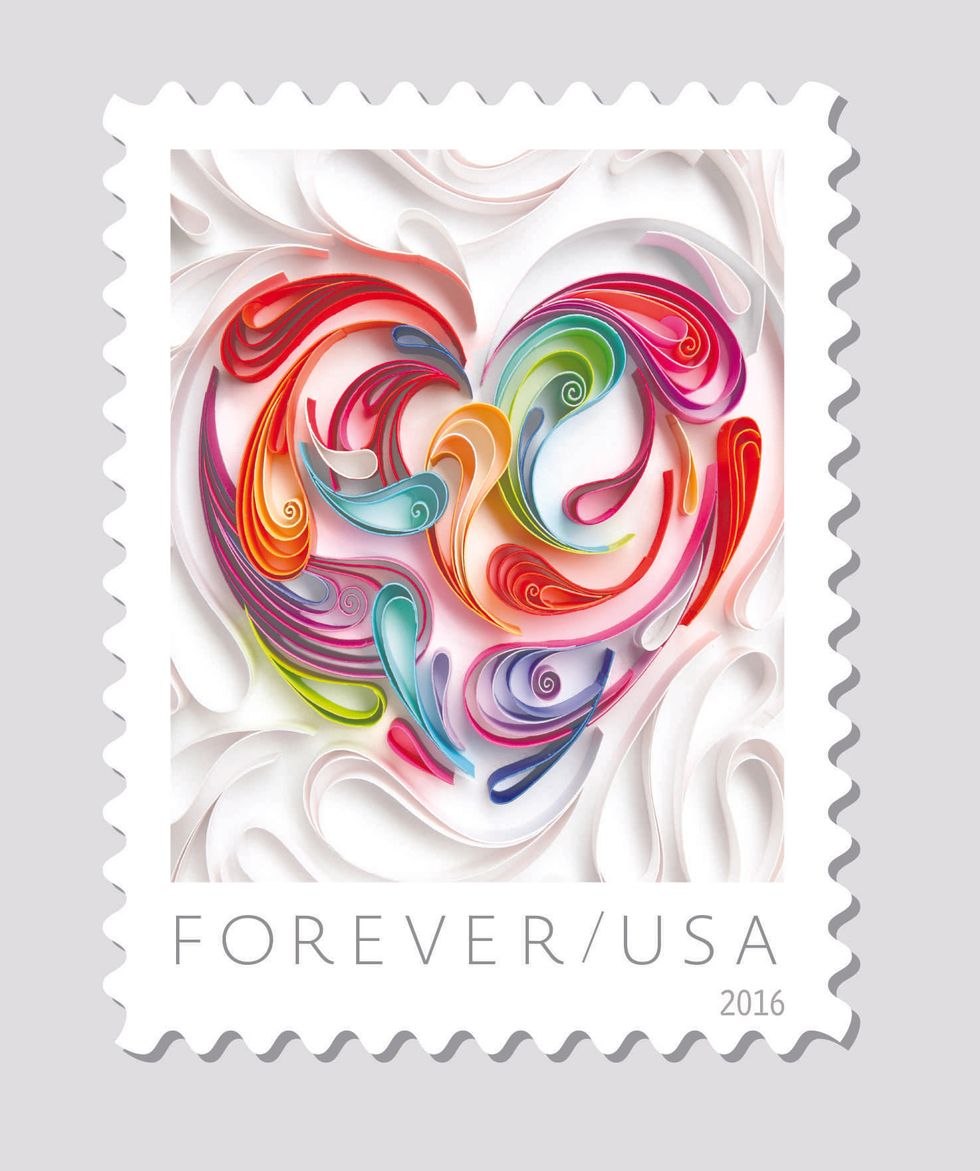

Putting a stamp on Norfolk

Feb 04, 2026

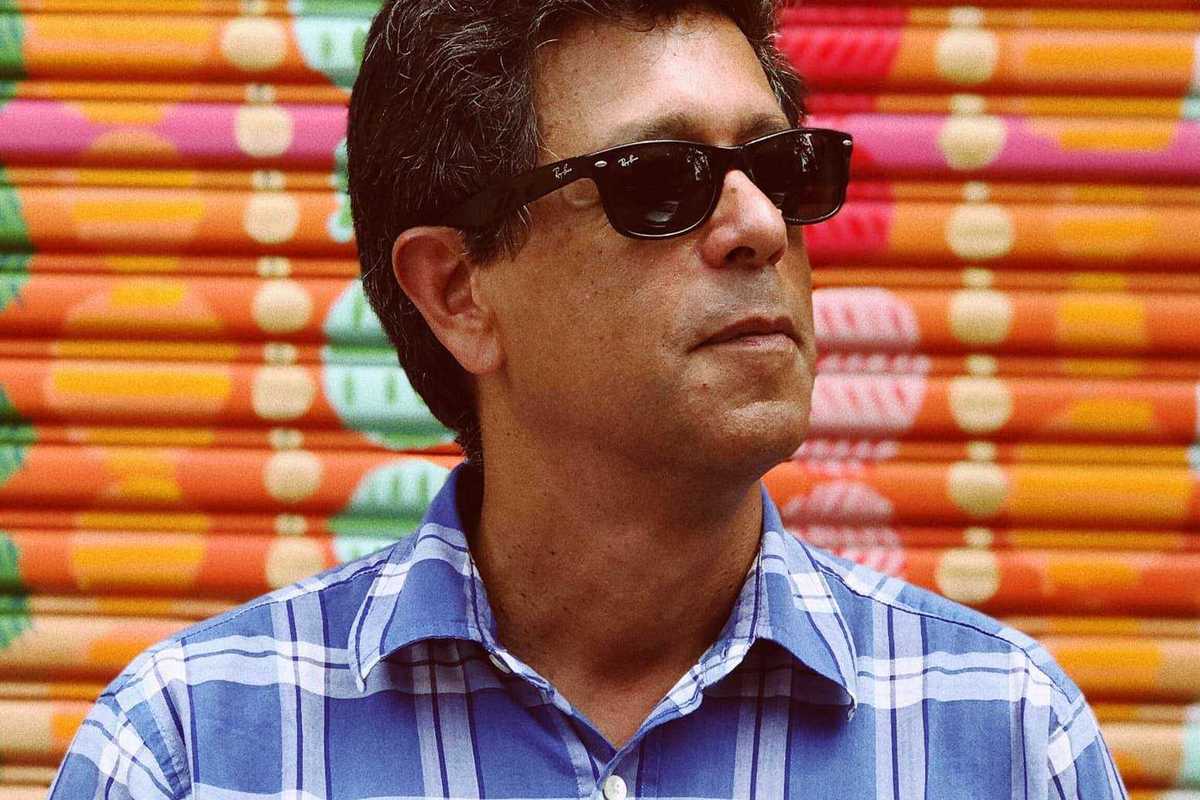

Antonio Alcalá

Provided

As part of the Norfolk Economic Development Commission’s campaign to celebrate the Norfolk Post Office and the three women who run it — Postmaster Michelle Veronesi and mother-and-daughter postal clerks Kathy Bascetta and Jenna Brown — the EDC has invited USPS art director and stamp designer Antonio Alcalá for a visit.

On Sunday, Feb. 8, at 3 p.m., the Virginia-based designer will give a talk at the Norfolk Library titled “The Art of the Postage Stamp.” The free talk is open to the public, with a reception following. Reservations are required: norfolklibrary.org.

On Saturday, Feb. 7, at 10:30 a.m., there will be a Children’s Valentine Stamp Workshop with Alcalá and children’s librarian Eileen Fitzgibbons. The workshop is open to children ages 6–14 (limit 14; registration required at norfolklibrary.org). The invitation: “Come create a stamp you love!”

Ann Havemeyer, executive director of the Norfolk Library, said, “It’s always fun to see the new stamps issued by the USPS and learn more about the process of bringing a stamp to life. Antonio Alcalá will speak about the history of stampmaking, the design elements involved, and his own journey that brought him to this work.”

Alcalá is the founder and co-owner of Studio A, a design practice working with museums and arts institutions. He lectures at schools including the Corcoran College of Art + Design, the School of Visual Arts, Pratt Institute and the Maryland Institute College of Art. His work and contributions to the field of graphic design were recognized with his selection as an American Institute of Graphic Arts Fellow. He serves on Poster House museum’s CMYK Council and the Smithsonian National Postal Museum’s advisory council. His designs are represented in the AIGA Design Archives, the National Postal Museum and the Library of Congress Permanent Collection of Graphic Design. Alcalá earned a bachelor’s degree in history from Yale University and an MFA in graphic design from the Yale School of Art. He lives in Alexandria, Virginia, with his wife and Studio A partner, Helen McNeill.

The Brookings Institution recently stated that “two and a half centuries after its founding, the Postal Service’s universal service mission continues to support local economic life, particularly in rural areas where stable, place-based infrastructure remains central to small-business activity.” Members of the Norfolk Economic Development Commission agree: “The Norfolk Post Office plays a unique and essential role in town life. Beyond its core function, it serves as a daily point of connection for residents and businesses and is a critical piece of local infrastructure that supports commerce, communication and community.”

Keep ReadingShow less

loading