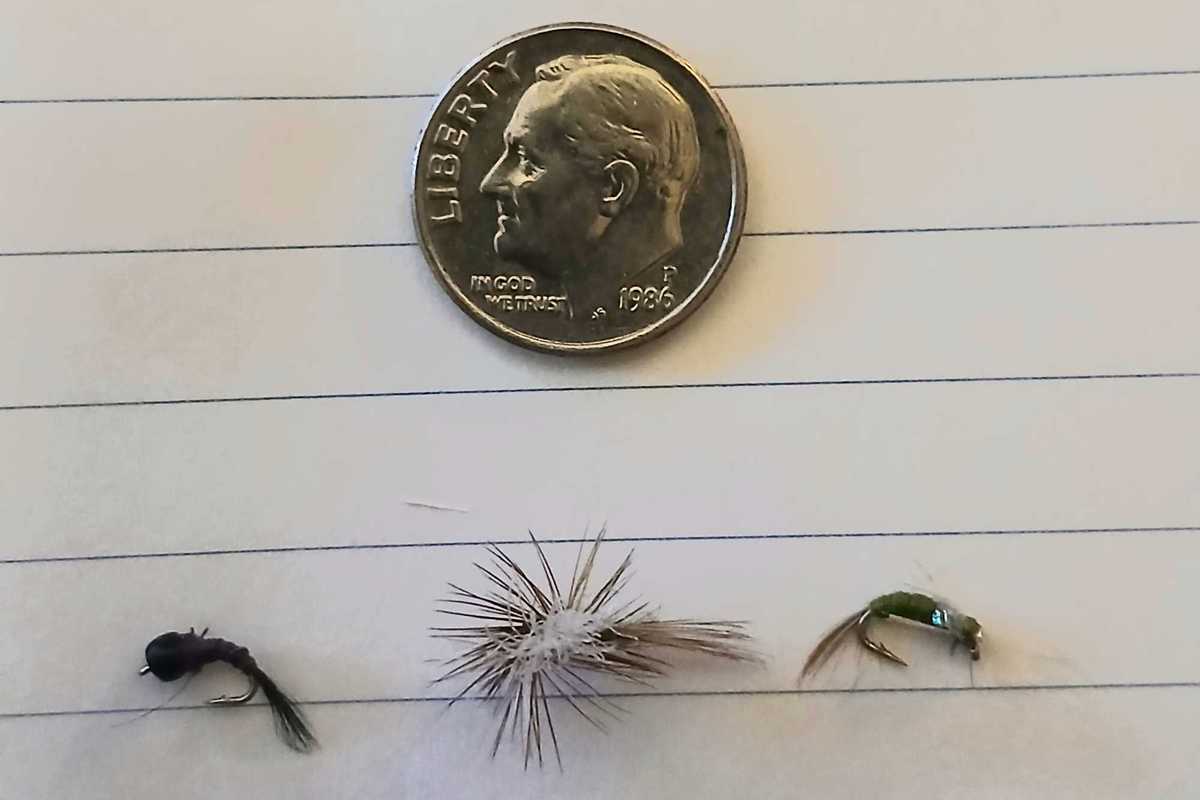

Woodpeckers reappear as spring nears

Woodpeckers have been making their presence known in recent weeks, in part thanks to the loud hammering noise they make as they search for bugs and begin to seek mates. This pileated woodpecker, spotted recently in Salisbury, carved out two holes in the trunk of an evergreen tree as it captured edible insects.

Photo by James H. Clark

lakevillejournal.com

lakevillejournal.com

Visitors consider Norman Rockwell’s paintings on Civil Rights for Look Magazine, “New Kids in the Neighborhood” (1967) and “The Problem We All Live With” (1963.) L. Tomaino

Visitors consider Norman Rockwell’s paintings on Civil Rights for Look Magazine, “New Kids in the Neighborhood” (1967) and “The Problem We All Live With” (1963.) L. Tomaino

Styling a tray can give a home or room a re-fresh.Kerri-Lee Mayland

Styling a tray can give a home or room a re-fresh.Kerri-Lee Mayland