At the turn of the other century, when our nation’s second-largest export was ice, behind cotton, our area was (literally) on the cutting edge of the industry, filling boxcars with ice bound for New York City and points south as far as Cuba.

Ice-harvesting boomed here from the mid-1800s until the 1930s, when the discovery of Freon made refrigerators commonplace. Before refrigeration, iceboxes kept food fresh and (sort of) cold as long as icemen came once a week to replenish “cakes” harvested from frozen lakes and stored in ice houses until needed.

“Icing was brutal, brutal hard work done under the worst possible weather conditions,” recalled Paul Rebillard in 1987 for the Salisbury Association’s Oral History Project. Not only was icing difficult, it was perilous. Nearly everyone on the crew “went in” at some time. Luckily, the day Paul fell in, “I had so many clothes on, I came up like a cork.” Dangerous as it was, the industry provided welcome employment to farmers and others without winter work. Click here for more from the 1987 interview.

Think you’d be up to the job? Pick a nice, cold day and go down to the lake with your ice auger. You know what that is, it looks like a giant corkscrew with a wood handle. You better be wearing mittens, not gloves, or Paul warned you’ll get frostbite. He advised wearing felt socks inside rubber boots. (LL Bean isn’t a thing yet.) Strap on crampons (serrated blades that give your boots traction) so you won’t slip as you drill a hole in the ice with your auger.

Drop your ice ruler into the hole. If the ice measures twelve inches, it’s time to yoke up your horse to the scraper. The best ice is frozen water with no snow mixed in. “A block so clean you can read a newspaper through it,” overpromises your competitor. Start scraping.

Once you’ve cleared a “field”, switch out the scraper for a scorer. Mark out blocks in two foot squares, creating a checkerboard pattern. This might be a good time to mention that your horse needs crampons, too. Be careful not to score too deep or your horse will fall through. Now, pick up your chisel.

“You chisel out the first block at the very center of your field,” said Jim Lamson, who worked for ten cents an hour harvesting Riga Lake. Jim was the voice of the Holley-Williams House Museum’s ice house for years, where his recorded memories introduced visitors like my daughters to a time when ice cream couldn’t be had every day.

Now, pick up your saw. Not a bendy little wood saw. You need a heavy ice saw, six feet long, teeth as big as a shark’s to get through twelve or more inches of ice. (Like the antique ice saw rescued from the bottom of Lake Wononscopomuc by Don Mayland, our ice marshal.)

Once the first block is out, a channel starts and you can float blocks to shore instead of carrying them. Good, because ice blocks weigh about 100 lbs. each. Load up your sled, then drive to the ice house. Stack neatly, leaving space at the top for cold storage: apples, butter, slabs of meat. Don’t forget to pack sawdust around the sides, for insulation, so your blocks won’t melt by the fourth of July.

After all this, how much can you charge for your ice?

A Lakeville bill of sale for February 1902 itemized $4.79 for 479 cakes, $6.50 for carting. But the price of ice was seasonal. It skyrocketed in summer when icemen made house calls, delivering blocks one by one as requested by cards left in porch windows. The idea that icemen “raked it in” explains lyrics of an 1899 hit song: I thought it was the house of a millionaire, but he told me the Iceman resided there.

How'd You Like to Be the Iceman? by Will F. Denny(1899)

Click here to listen at Archive.org.

Are any ice houses still standing? The Holley-Williams House is now privately owned, but its ice house is protected by a Historic Preservation Easement through the Salisbury Association and Historic New England.

In Winchester, an ice house built in the 1840s is a two-bedroom VRBO rental. In Sharon, The Icehouse Project Space showcases contemporary art projects in an 18th-century ice house. At the Sharon Audubon Center, the Ford family’s former ice house is a sugar house where maple syrup is made.

But perhaps the most unique use of a former ice house is in Winsted where Stew Jones converted a commercial ice house on Highland Lake to a site for the restoration of antique Jaguar cars. Scenes from the shop, including pictures of the old ice house, are shown in a documentary film by Elias Olsen about Stew Jones.

Helen Klein Ross lives in Lakeville and is the author of “The Latecomers,” a novel set in ice-cutting days. Research for this column included kind input from Lou Bucceri, Tom Callahan, Katherine Chilcoat, Eileen Fielding, Stew Jones, Don Mayland, Jean McMillen and members of Northwest Corner Chatter and Salisbury, Connecticut Facebook pages. Any errors are her own.

Kent's Ainsley Moffitt takes a shot against the Millbrook goalie.Photo by Lans Christensen

Kent's Ainsley Moffitt takes a shot against the Millbrook goalie.Photo by Lans Christensen Lily Kennedy on attack for Millbrook.Photo by Lans Christensen.

Lily Kennedy on attack for Millbrook.Photo by Lans Christensen. Ainsley Moffitt celebrates after scoring a goal for Kent.Photo by Lans Christensen

Ainsley Moffitt celebrates after scoring a goal for Kent.Photo by Lans Christensen

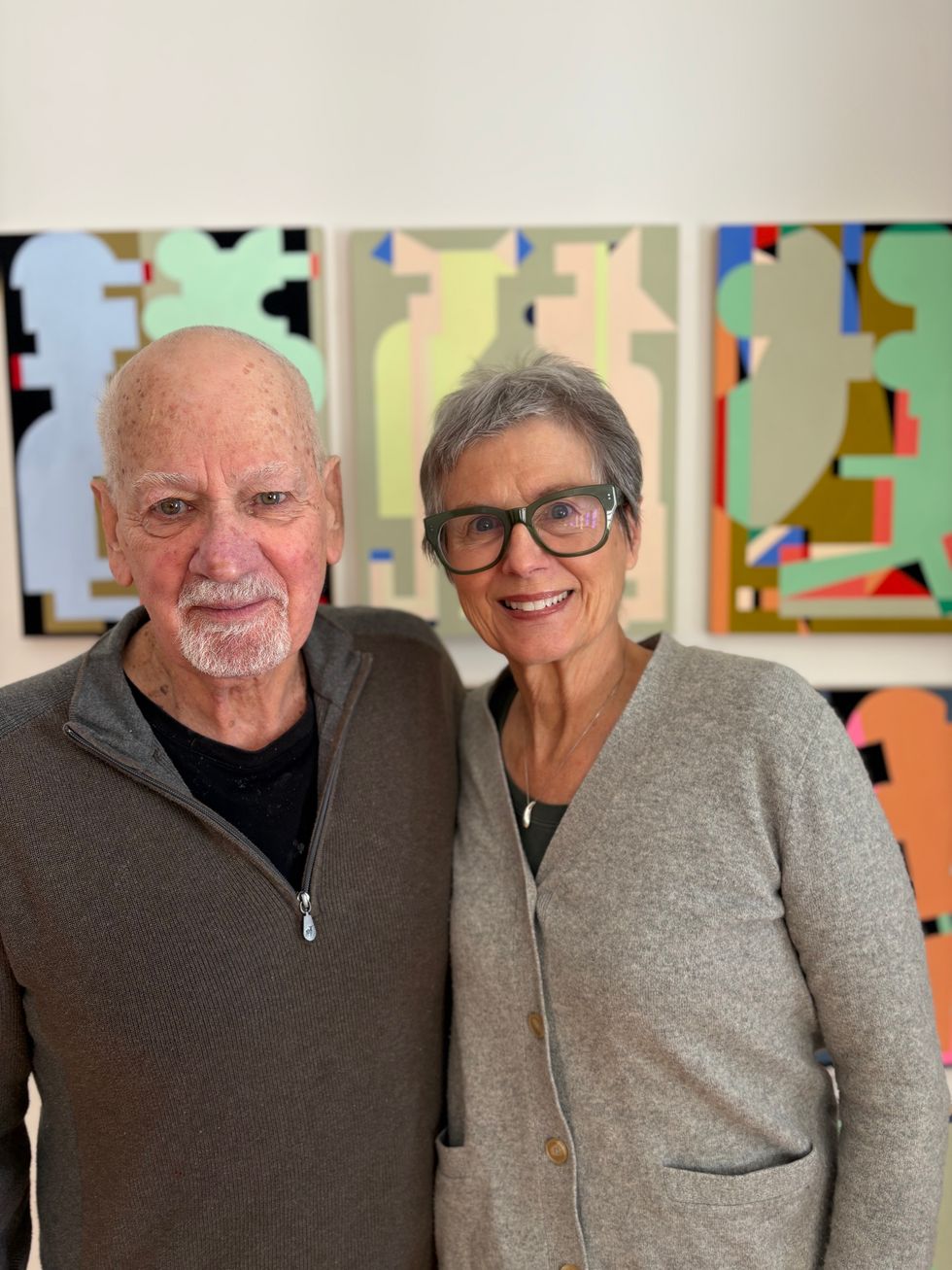

Plagens and Fendrich at home in front of some of Fendrich’s paintings. Natalia Zukerman

Plagens and Fendrich at home in front of some of Fendrich’s paintings. Natalia Zukerman

The Northwest Corner’s Ice Age: ‘Brutal hard work’