Latest News

Classifieds - October 23, 2025

Oct 22, 2025

Help Wanted

Weatogue Stables has an opening: for a full time team member. Experienced and reliable please! Must be available weekends. Housing a possibility for the right candidate. Contact Bobbi at 860-307-8531.

Services Offered

Hector Pacay Service: House Remodeling, Landscaping, Lawn mowing, Garden mulch, Painting, Gutters, Pruning, Stump Grinding, Chipping, Tree work, Brush removal, Fence, Patio, Carpenter/decks, Masonry. Spring and Fall Cleanup. Commercial & Residential. Fully insured. 845-636-3212.

SNOW PLOWING: Be Ready! Local. Sharon/Millerton/Lakeville area. Call 518-567-8277.

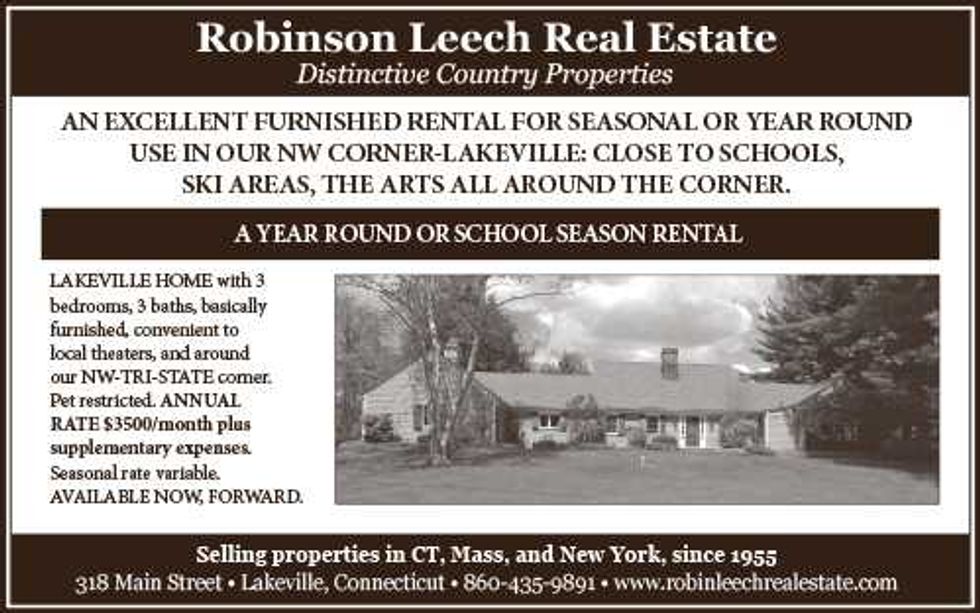

Real Estate

PUBLISHER’S NOTICE: Equal Housing Opportunity. All real estate advertised in this newspaper is subject to the Federal Fair Housing Act of 1966 revised March 12, 1989 which makes it illegal to advertise any preference, limitation, or discrimination based on race, color religion, sex, handicap or familial status or national origin or intention to make any such preference, limitation or discrimination. All residential property advertised in the State of Connecticut General Statutes 46a-64c which prohibit the making, printing or publishing or causing to be made, printed or published any notice, statement or advertisement with respect to the sale or rental of a dwelling that indicates any preference, limitation or discrimination based on race, creed, color, national origin, ancestry, sex, marital status, age, lawful source of income, familial status, physical or mental disability or an intention to make any such preference, limitation or discrimination.

Keep ReadingShow less

School spirit on the rise at Housy

Oct 22, 2025

Students dressed in neon lined the soccer field for senior night under the lights on Thursday, Oct. 16. The game against Lakeview was the last in a series of competitions Thursday night in celebration of Homecoming 2025.

Hunter Conklin and Danny Lesch

As homecoming week reaches its end and fall sports finish out the season, an air of school spirit and student participation seems to be on the rise across Housatonic Valley Regional High School.

But what can be attributed to this sudden peak of student interest? That’s largely due to SGA. Also known as the Student Government Association, SGA has dedicated itself to creating events to bring the entire student body together. This year, they decided to change some traditions.

Spirit week from Oct. 14-17 was unlike those of the previous years. From wearing Housatonic merch to Boomer vs Baby day, this year’s spirit week held a little friendly competition to see which grade could participate the most.

“I think that students are bored of the same old activities and events, so it’s good to switch things up even slightly to incentivize interest within students,” said SGA president and senior Mollie Ford. “Plus the point system is super beneficial because it gives students a reason to participate.”

The school spirit sentiment can be seen outside of just the school. Senior Simon Markow is known for his photography throughout the community, and has dedicated time to help Housy sports teams’ social media posts.

“Since I’ve started photography, I think school attendance [at sports games] has gone up,” Markow said. “I feel this year, students will be more aware of games and are more likely to be at the games.”

Whether it’s a pink-out volleyball game or an under the lights soccer match, it’s likely you’ll see some familiar faces.

Social media has played a large role in this over the years. Almost every student organization at Housatonic has an Instagram account, and it’s helped reach students more efficiently than a poster or email would.

“The increase of social media use, with the help from me but as well as the teams themselves has definitely increased student interest,” Markow said. “With Housy teams posting more about their upcoming games, and my help showing the cool goals, spikes, or touchdowns, it’s enlightened students to watch the games themselves.”

In a small school, promoting pride has proven to be a challenge. But this year’s senior class has made some adjustments in the hopes to change that.

“The SGA community has spent the last few years really focusing on student participation, because we think it’s the students who contribute to a better climate,” Ford said. While Housatonic’s student body may be small in size, it seems they certainly aren’t small in spirit.

Keep ReadingShow less

The poster promoting the Homecoming dance boasted the event would feature dancing, games and a bonfire. Reactions to the planned move outside were mixed, with some students excited about the changes and others expressing a desire for tradition.

Provided

The weekend of Homecoming at HVRHS was packed with events including rival games under the lights, senior night, and a new take on Homecoming that moves it outside — and it wouldn’t have been possible without the students of Housatonic.

Orchestrating was no easy feat, especially considering much of the work was left up to the students.

Historically, HVRHS has hosted night games for boys and girls soccer and the GNH football team, but when members of the soccer team asked the athletic director, Anne MacNeil, she left it up to the students to acquire the lights necessary to host a night game.

“I said, ‘Hey, if you can find the lights, we can make it happen,’” MacNeil said. “I usually take control of it, but I really wanted to have the teams have the initiative and take responsibility for it. I think by having them do that, they have a lot more invested in it.”

Finding lights for the game was a challenge in and of itself, and it fell on the students, parents, and alumni to come together if there was to be a night game at all.

Luckily for the players, Patricia and Dino Labbadia, parents of senior Anthony Labaddia, were able to amass the support of the community and get all the necessary equipment donated for the night game.

“We’re fortunate with our communities. Our parents know people in communities and they were able to ask… [and] find the resources,” MacNeil said. “We’ve got a great senior group and senior parent group who have really taken charge … and really made the whole season possible.”

In the end, the night came together spectacularly, and the senior ceremonies, rivalry games, and nighttime fixtures made for a memorable night on the day before Homecoming.

The action began at 4 p.m. Thursday, when the JV Girls Volleyball team played rivals Lakeview High School at home.

At 4:30, the middle school boys soccer team as well as the cross country team faced Northwestern at Housatonic’s lower field and cross country course respectively. Also at 4:30, the JV boys soccer team took on rival Lakeview at Housatonic’s upper field.

At 5:15, the girls varsity volleyball team honored their seniors at Housatonic’s Senior Night ceremony, including captains Katie Crane and Victoria Brooks, before an intense match against Lakeview.

At 6:15, the boys varsity soccer team honored their seniors, including captains Everet Belancik and Abram Kirshner, before kicking off under the lights at Housatonic’s upper field against the Bobcats.

Friday night changes

Typically, Homecoming is hosted in the cafeteria with a DJ and the entire room open as a dance floor. Dancing is the main event, with a small photo op stationed next to one of the exits.

The typical formal dance filled with LED lights and glitter looked a bit different this year. For the HVRHS 2025 Homecoming, the activities all took place outside. There was a large bonfire for students to hang around, a tented area perfect for dancing, and lawn games to play.

The inspiration for this change comes from the Homecoming hosted during the COVID-19 social distancing restrictions put into place at the time. Senior class President Madison Graney said “Other years passed, graduating classes really enjoyed it and we wanted to give it a try.”

Although the theme of Homecoming remains the same, new tasks came in preparation for the event. Including the Bonfire “adds a whole new component,” Graney said. “[We] have to contact the fire department to ensure that the bonfire is being contained.” Hosting the dance outside also demanded “more preparation the day before … set up the tents and make sure it’s a safe and fun space for everyone to enjoy.”

Opinions about Homecoming’s new look vary amongst the student body, with some excited for change and others comfortable with the familiarity of an inside dance. Alexa Meach, an HVRHS senior, expressed that “Everyone that I’ve talked to’s plan is to get dressed up, take photos, and then change into more comfortable clothes because it’s going to be freezing. I feel like we could have had a different event for the bonfire. I think they could have been two separate events.”

Graney said the change is “A really great way to change up the tradition ... [and] another good way to get to know your peers and your teachers and interact with the student body all at once.”

Keep ReadingShow less

Housy takes on Halloween

Oct 22, 2025

Housatonic Valley Regional High School

File photo

As the chilly breeze settles in, Halloween approaches and the community yearns for spooky festivities — HVRHS has answered that calling. An event held annually for the past eight years, the HVRHS haunted house has returned.

The event is organized by the current senior and junior year classes — 2026 and 2027 respectively — and held to raise money that goes toward the junior and senior class’s activities such as senior week, prom, the senior class trip, and more.

The haunted house is a significant event for HVRHS students, with the Class of 2026’s Vice President Richie Crane saying it is “actually one of our bigger fundraising events.” The profits raised by the classes are split based on how much either class participates, as Crane explained: “We split evenly between the juniors and the seniors, so if the juniors help as much as the seniors then we split the profit with them.” The profits shared between the classes is typically “a couple thousand dollars,” said Anne MacNeil, HVRHS’s sports director and one of the chaperones at the first haunted house.

In regards to planning such a large event, there are “several meetings that first start off with getting a theme … then finding a leader for each section … and then recruiting the people to participate.” MacNeil said. Costs going into planning the event are minimal, as they try to reuse as much materials as possible. If there are materials that need to be purchased, the cost is covered from the profits made at the end of the event, Crane said.

Working at the HVRHS haunted house provides students with an invaluable experience where they learn leadership skills, organizational skills, and teamwork. During the planning process, some students volunteer for leadership roles, where they are in charge of a designated section of the school and the people within that section. As a section leader, the student is in charge of setting up props, managing their area, and ensuring the people in their section are on task. Leaders dedicate “almost 12 hours of [their] day to a section of Housy” said Crane, giving the students a great opportunity to practice leadership skills.

The HVRHS haunted house is a holiday tradition that brings fun, community, and opportunities to the high school. MacNeil finds it to be “a lot of fun for the students to put on and a great thing for the community to enjoy.” Come support the Class of 2026 and 2027 and see the HVRHS haunted house for yourself on Nov. 1, 2025.

Keep ReadingShow less

loading