Latest News

In remembrance:

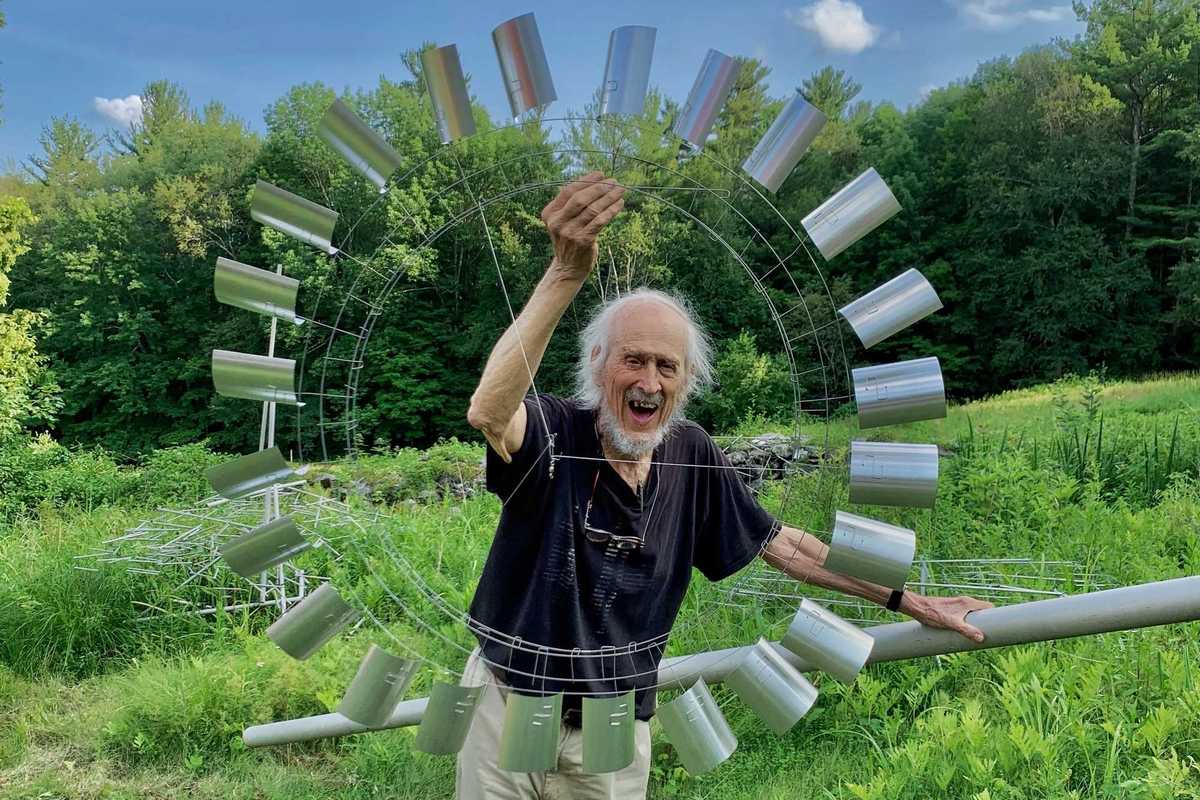

Tim Prentice and the art of making the wind visible

In remembrance:

Tim Prentice and the art of making the wind visible

There are artists who make objects, and then there are artists who alter the way we move through the world. Tim Prentice belonged to the latter. The kinetic sculptor, architect and longtime Cornwall resident died in November 2025 at age 95, leaving a legacy of what he called “toys for the wind,” work that did not simply occupy space but activated it, inviting viewers to slow down, look longer and feel more deeply the invisible forces that shape daily life.

Prentice received a master’s degree from the Yale School of Art and Architecture in 1960, where he studied with German-born American artist and educator Josef Albers, taking his course once as an undergraduate and again in graduate school.In “The Air Made Visible,” a 2024 short film by the Vision & Art Project produced by the American Macular Degeneration Fund, a nonprofit organization that documents artists working with vision loss, Prentice spoke of his admiration for Albers’ discipline and his ability to strip away everything but color. He recalled thinking, “If I could do that same thing with motion, I’d have a chance of finding a new form.”

What Prentice found through decades of exploration and play was a kind of formlessness in which what remains is not absence, but motion. To stand before one of his sculptures is to witness a quiet choreography where metal breathes, shadows shift and time softens.

After Yale, Prentice co-founded the architectural firm Prentice & Chan in 1965. The firm designed affordable housing projects in New York City, work largely led by partner Lo-Yi Chan. Prentice also designed custom single-family homes and continued to develop sculptural ideas alongside his architectural practice. After leaving the firm in 1975 and eventually relocating full time to Cornwall, he undertook a range of local architectural projects while increasingly devoting himself to sculpture.

Prentice began producing larger-scale sculptural commissions in the 1970s, during a period of national expansion in public art funding tied to new building projects. His first major commission came in 1976 from AT&T, helping launch a career that would bring his kinetic installations to corporate, institutional and public spaces across the United States and abroad. While his work follows in the lineage of Alexander Calder and George Rickey, critic Grace Glueck observed that its “gently assertive character is very much his own.”

In Cornwall, Prentice established a studio devoted to designing and fabricating kinetic sculpture, where he continued working for decades. He had many assistants over the years including local artists David Bean, Ellen Moon and Richard Griggs. David Colbert worked with Prentice for many years, assisting with fabrication, installation and project development and in 2012, Prentice established Prentice Colbert Inc., helping ensure that fabrication and development of large-scale commissions could continue beyond his lifetime.

Colbert said Prentice could be imperious, but came to understand that he valued thoughtful critique over agreement. “That evolved into a free and easy give-and-take, along with some fierce arguments,” he said. “Our relationship was always developing, right through to the end.”

In the mid-1990s, Prentice was diagnosed with macular degeneration, a condition that gradually narrowed his field of vision. Rather than turning away from the visual world, he leaned further into it, focusing on movement, light and peripheral perception — on what could be felt as much as seen. The Vision & Art Project film documents this period of his life and the ways he adapted his creative process.

Even in his final years, Prentice continued experimenting. In the summer of 2025, he created a series of drawings titled “Memory Trees,” produced from recollection as his eyesight declined. The series sold out at the Rose Algrant show that August, offering a poignant example of an artist adapting and creating throughout their lifetime.

“He was interested in whimsy,” said Nora Prentice of her dad. “But he also worked seven days a week,” she said. “He’d come in for dinner and then go right back out.” His studio was known for its atmosphere of curiosity and play, with music often drifting through the workspace as sculptures moved overhead in careful, measured rhythms. His work reminds viewers how profoundly small movements shape perception, and how change itself may be the only constant.

In his poem “Among School Children,” William Butler Yeats asks, “How can we know the dancer from the dance?” Prentice offered his own answer. “I’m not making the dance,” he said. “The wind is making the dance.”

As Nora reflected, “I think that’s how he would want to be remembered: for making the wind visible.”

Keep ReadingShow less

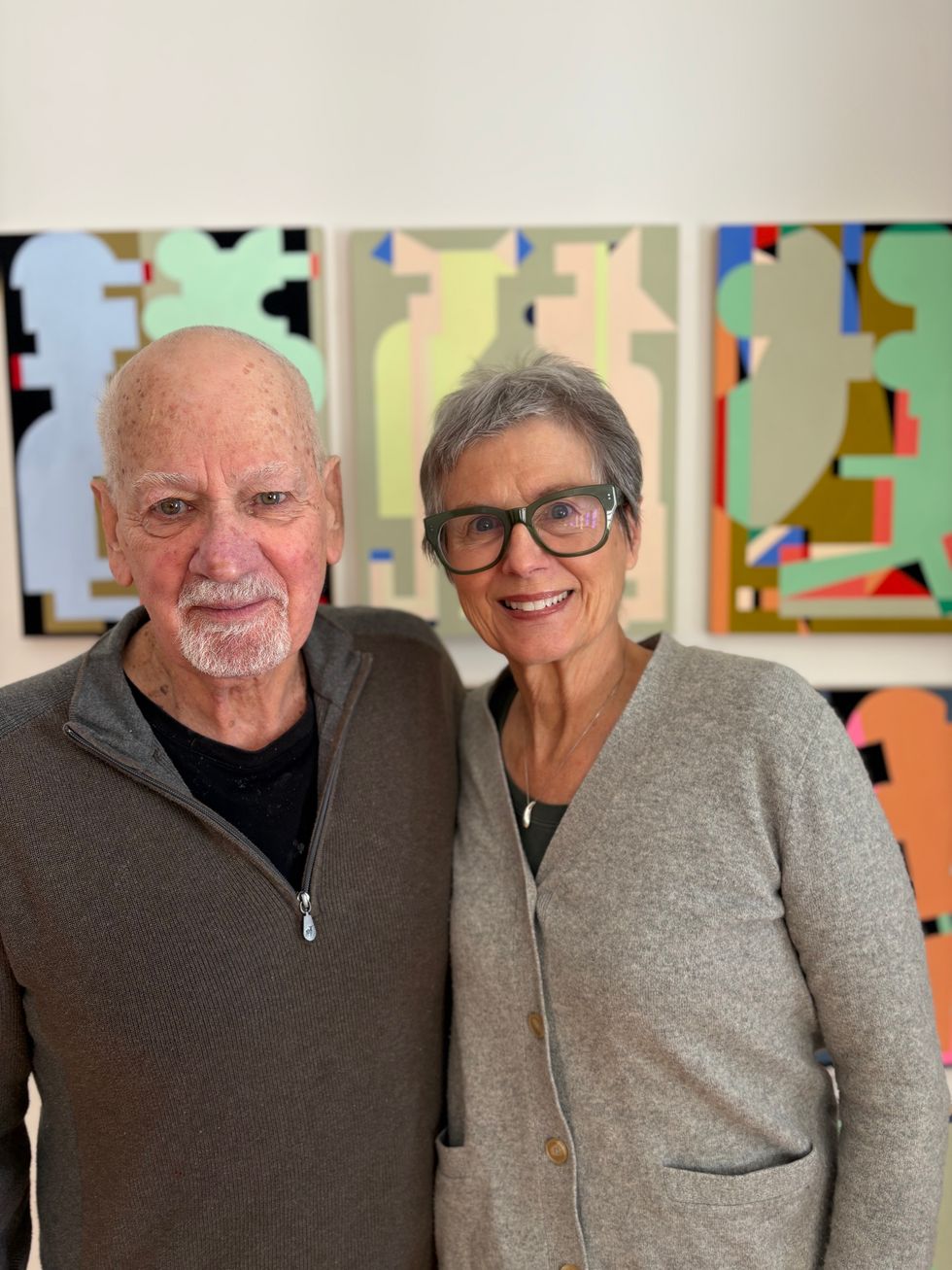

Laurie Fendrich and Peter Plagens at home in front of one of Plagens’s paintings.

Natalia Zukerman

He taught me jazz, I taught him Mozart.

Laurie Fendrich

For more than four decades, artists Laurie Fendrich and Peter Plagens have built a life together sustained by a shared devotion to painting, writing, teaching, looking, and endless talking about art, about culture, about the world. Their story began in a critique room.

“I came to the Art Institute of Chicago as a visiting instructor doing critiques when Laurie was an MFA candidate,” Plagens recalled.

“He was doing critiques with everyone,” Fendrich said of Plagens. “We met at one of those sessions and, well, what can I say. We fell in love instantly.”

Fendrich speaks candidly about the pressures that shaped her early life choices. “We both married the first time at 21, which a good number of women of my generation did without much thought.” Her first husband was a good guy, she says, but “we weren’t suited for each other at all, even though he suited my parents perfectly.” Her decision to get a divorce was seismic. “My mother didn’t speak to me for a year.” Time softened the rupture. “One day she told me, ‘I see now why you left.’”

Fendrich had a rigorous liberal arts education at Mount Holyoke. “I studied painting and drawing, but I also got interested in political philosophy. Plato, Aristotle, Machiavelli — Rousseau was my big guy — Tocqueville, everybody. And I still read them.” Plagens’s path was less formal. “I went to USC at 17,” he said, “and declared English as my major. It was a frat school, and I was in one for the first two years. Then I started doing the cartoons for the Daily Trojan, took a couple art classes, and thought, ‘Wait a minute, I like this.’”

Culturally, they diverged just as sharply. “I came from a fairly puritanical family that didn’t even go to the movies,” Fendrich said. Plagens, by contrast, grew up immersed in pop culture. “My father was an omnivorous reader,” he said, “and a jazz fan, and he shared these passions with me.” In 1966, Plagens walked into Artforum’s LA office and said, “I want to write reviews.” He was paid five dollars per piece. “Gasoline was 23 cents a gallon, so it went a long way.”

Over time, the couple slowly fused their educations. “He taught me jazz, I taught him Mozart,” Fendrich said with a laugh. “I’ve had a movie education from him; he read Jane Austen because of me.”

During their early years in LA, Plagens taught at USC, and Fendrich at Art Center College of Design. In 1985, they decided “our kind of abstraction would do better in New York,” as Fendrich put it. “So, we up and moved to Tribeca with $10,000 and a toddler.”

Both artists grounded their artistic careers in teaching and writing. “Teaching, which I loved, gave me the financial stability to be an artist,” Fendrich said, reflecting on her 27 years as a professor at Hofstra. “It meant that being an artist didn’t require I make money from every show. I didn’t start writing until 1999, but though I write for publication frequently, I make hardly any money at it.”

Artistically, they guard each other’s independence. “We have unspoken rules,” Plagens said. “You don’t comment on someone’s work while they’re in the middle of creating it.” Critique comes by invitation only. “He’s not mean, just direct,” said Fendrich. Over time, their aesthetics have subtly converged. “My work has gotten cleaner from looking at his,” she said. “He’s gotten more colorful because of me.”

The two have had several two-person exhibitions. At a recent duo show at the Texas Gallery in Houston “Laurie’s paintings flew off the wall,” Plagens recalled. “Me, well, not so much.”

Plagens’s parallel career in journalism shaped their lives in tangible ways. He worked as art critic at Newsweek from 1989 until 2003 and currently contributes reviews of museum exhibitions to The Wall Street Journal. “Being at Newsweek was one of the luckiest breaks I ever had,” he said. “They paid me to see things I would gladly pay to see.”

Their creative processes mirror their personalities. “I start with a specific idea,” Fendrich said, “and then modify things as I paint.” Plagens laughed. “I start with complete mush, just blurting it out and spending the rest of the time fixing it.”

In 2019, they made what Fendrich calls “a decision of contraction.” They left the TriBeCa loft they had lived in for three decades, sold their Catskills home with its large studio, and moved full-time to a former auto repair shop in Lakeville, now a house where each has a studio, and the ground floor retains the open feel of a loft.

What sustains them in life, art and love, decades in, are endless conversations — and arguments — about art, history, exhibitions, books and movies. That exchange, ongoing and rigorous, may just be the masterpiece of their shared life.

Keep ReadingShow less

Want more of our stories on Google? Click here to make us a Preferred Source.

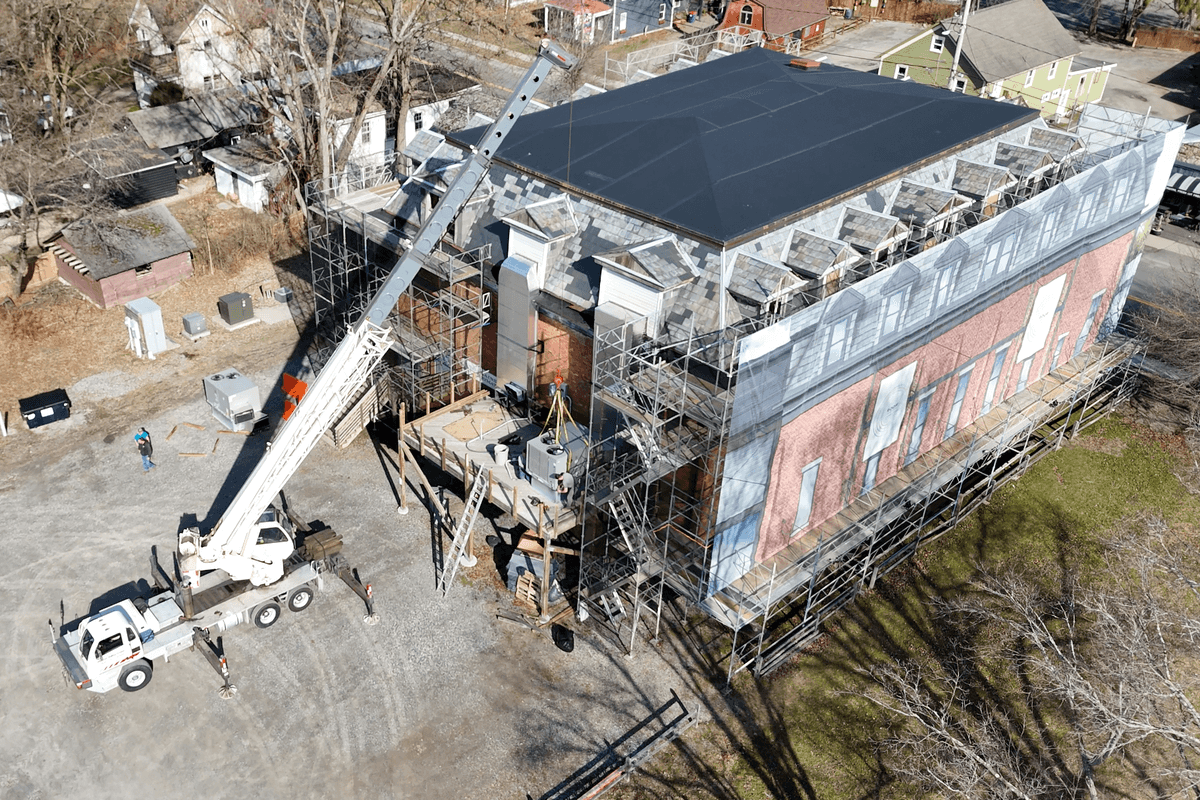

Hyalite Builders is leading the structural rehabilitation of The Stissing Center in Pine Plains.

Provided

For homeowners overwhelmed by juggling designers, architects and contractors, a new Salisbury-based collaboration is offering a one-team approach from concept to construction. Casa Marcelo Interior Design Studio, based in Salisbury, has joined forces with Charles Matz Architect, led by Charles Matz, AIA RIBA, and Hyalite Builders, led by Matt Soleau. The alliance introduces an integrated design-build model that aims to streamline the sometimes-fragmented process of home renovation and new construction.

“The whole thing is based on integrated services,” said Marcelo, founder of Casa Marcelo. “Normally when clients come to us, they are coming to us for design. But there’s also some architecture and construction that needs to happen eventually. So, I thought, why don’t we just partner with people that we know we can work well with together?”

Traditionally, homeowners hire designers, architects and contractors separately, a process that can lead to miscommunication, budget overruns and design revisions once construction begins. The new partnership seeks to address those challenges by creating a unified team that collaborates from the earliest planning stages through project completion.

“We can explore possibilities,” Marcelo said. “Let’s say the client is not sure which direction they want to go. They can nip that in the bud early on — instead of having three separate meetings with three separate people, you’re having one collaborative meeting.”

The partnership also reflects an expanded view of design, moving beyond surface aesthetics to include structural, environmental and performance considerations. Marcelo said her earlier work in New York City shaped that perspective.

“I had a 10-year career in New York City designing townhouses and penthouses, thinking about everything holistically,” she said. “When I got here and started my own business, I felt like I was being pigeonholed into only the decorative part of design. With the weight of an architect on our team now, it has really helped us close those deals with full home renovations, ground up builds and additions.”

The team emphasizes what it describes as high-performance design, incorporating modern building science, energy efficiency and improved air quality alongside aesthetic goals.

“If you’re still living inside 40-year-old technology and building techniques, we haven’t really handed off the best product we could,” said Soleau. “The goal is to not only to reach that level of aesthetic design but to improve the envelope, improve the living environment within a home and bring homes up to elevated standards of high-performance building.”

This integrated approach has proven particularly useful for renovation projects, where modern materials and systems can be thoughtfully incorporated into older structures. The firms also prioritize durability and long-term functionality, often incorporating antiques, vintage elements and high-quality materials designed to support clients’ lifestyles.

“I’m very big on investing in pieces that are going to be quality and last you the test of time,” Marcelo said. “Not just designing for a five- to 10-year run, but really designing for the long haul.”

The collaboration is already underway on several projects, including a major renovation in Sharon that involves rebuilding a 1990s modular home to maximize views while upgrading structural and performance systems. The firms are also exploring advanced visualization technology that would allow clients to experience projects through virtual reality before construction begins.

“For me, as somebody who wants to take the project all the way from beginning to end and make the process as effortless as possible for my client, it’s easier to do that with collaboration and a team than to do it alone,” Soleau said. “Most clients, especially second-home owners, want a team that can lead the project from concept through completion; aligning design, budget, and construction.”

On Feb. 19, the three firms will officially launch the initiative at an invitation-only event at The Stissing Center in Pine Plains, where Hyalite Builders is leading the structural rehabilitation of the historic building. A limited number of “hard hat tour” reservations will be available by request, providing rare, behind-the-scenes access while work is actively underway. Those interested in attending may contact event organizer Lauren Fritscher of Berkshire Muse at hello@berkshiremuse.com.

Keep ReadingShow less

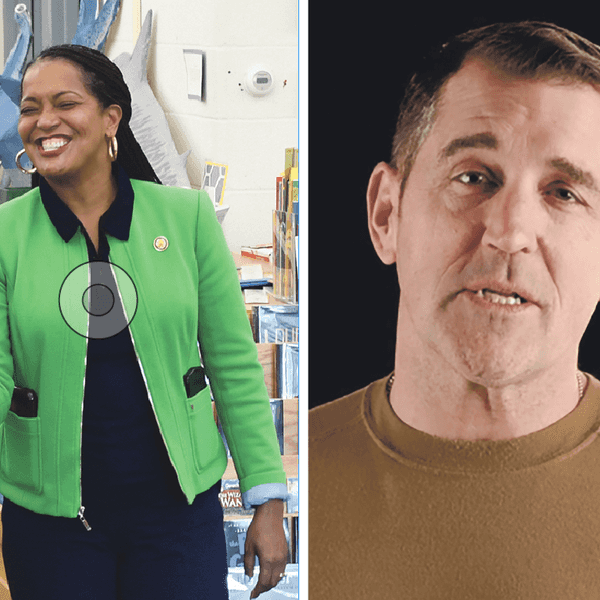

Autumn Knight will perform as part of PS21’s “The Dark.”

Provided

This February, PS21: Center for Contemporary Performance in Chatham, New York, will transform the depths of midwinter into a radiant week of cutting-edge art, music, dance, theater and performance with its inaugural winter festival, The Dark. Running Feb. 16–22, the ambitious festival features more than 60 international artists and over 80 performances, making it one of the most expansive cultural events in the region.

Curated to explore winter as a season of extremes — community and solitude, fire and ice, darkness and light — The Dark will take place not only at PS21’s sprawling campus in Chatham, but in theaters, restaurants, libraries, saunas and outdoor spaces across Columbia County. Attendees can warm up between performances with complimentary sauna sessions, glide across a seasonal ice-skating rink or gather around nightly bonfires, making the festival as much a social winter experience as an artistic one.

The Dark’s lineup includes several world and U.S. premieres. Highlights include Thomas Feng performing “Night Prayers,” a program of compositions by late Ethiopian composer and Orthodox nun Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou; Phil Kline’s outdoor participatory score “Force of Nature (February);” an audiovisual collaboration between composer David Lang and Academy Award-nominated filmmaker Bill Morrison; an interdisciplinary performance by Lee Ranaldo of Sonic Youth and multimedia artist Leah Singer; and “We Survived the Night: A Coyote Story in Four Parts” by Julian Brave NoiseCat.

For more information about The Dark or to purchase tickets, visit ps21chatham.org/the-dark

Keep ReadingShow less

Exterior of the Linde Center for Music and Learning.

Mike Meija, courtesy of the BSO

The Tanglewood Learning Institute (TLI), based at Tanglewood, the legendary summer home of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, is celebrating an expanded season of adventurous music and arts education programming, featuring star performers across genres, BSO musicians, and local collaborators.

Launched in the summer of 2019 in conjunction with the opening of the Linde Center for Music and Learning on the Tanglewood campus, TLI now fulfills its founding mission to welcome audiences year-round. The season includes a new jazz series, solo and chamber recitals, a film series, family programs, open rehearsals and master classes led by world-renowned musicians.

“We have been thrilled and humbled to see the Tanglewood Learning Institute embraced as a year-round destination for a breadth of exceptional programming, including classical, jazz and family-friendly events,” said BSO President and CEO Chad Smith. “Our 2025–26 fall, winter and spring season reflects our deepening commitment to engaging the vibrant, year-round Berkshires community and to fully exploring the potential of TLI as a space where BSO programs make thought-provoking connections between music, art and society.”

TLI is once again presenting its Chamber Concerts series on Sunday afternoons, with small ensembles of BSO musicians performing familiar favorites and classic mainstays, as well as new music by contemporary composers. There are upcoming chamber concerts scheduled for Feb. 22, March 8 and March 15.

New this season is the TLI Jazz series, which continues March 20 with the Sullivan Fortner Trio, led by Grammy Award-winning artist and educator Sullivan Fortner, whose eponymous ensemble won the 2024 DownBeat Critics Poll for Rising Jazz Group. “Soul-sax sensation” Nick Hemp brings his free-blowing blend of “barroom excitement and modern jazz finesse” for a rousing night of soul jazz April 10. Rounding out the jazz series, and back by popular demand, is Grammy Award-winning trumpeter and singer Jumaane Smith, who brings his repertoire of jazz and American Songbook standards to the Linde Center on May 9.

Another season highlight comes April 12 with an animated live concert screening of the 3D stop-motion adventure film “Magic Piano.” Produced by the Academy Award-winning BreakThru Films production company in Poland, the film will be accompanied by a screening of “The Chopin Shorts,” a collection of animated films set to Chopin’s etudes, performed by pianist Derek Wang.

All performances take place in Studio E, the Linde Center’s 4,000-square-foot multiuse room that serves as TLI’s main performance and event space. It features retractable seating, acoustic and technical systems, flexible configurations, and is accessible and comfortable for all patrons.

The entire Linde Center for Music and Learning is worth a visit in itself. The complex, which also includes the informal Cindy’s Cafe (seasonal) for a quick bite, is conceived not as a single building but as a cluster of pavilion-like spaces connected by an outdoor covered walkway and arranged around a century-old red oak tree. The center promotes a welcoming and serene sense of place and continuity with the rolling Tanglewood lawn and surrounding woodlands.

Smith said, “This ongoing work is also a passion project for our musicians, who form deep ties to the area and are eager to remain active in the Berkshires beyond the summer months. We look forward to welcoming new and returning audiences to experience all that TLI offers — all year long.”

The Tanglewood Learning Institute is located at 3 W. Hawthorne Road, Lenox, Mass. For more information and to purchase tickets,

visit bso.org/tli.

Keep ReadingShow less

Want more of our stories on Google? Click here to make us a Preferred Source.

loading