I recently enjoyed joining a group of people at the Miles Wildlife Sanctuary to participate in Sharon Audubon Center’s Purple Martin bird banding.

The sanctuary is the perfect location for clusters of their gourd-shaped homes because they are colony-nesting birds and prefer open areas with clear paths for flight or swooping. Access to water helps them find food more easily. Surprisingly, Purple Martins also like to be near human activity.

Long before Europeans arrived, Indigenous people noticed that Purple Martins moved into gourds they had hung up to dry. They found that the birds, which primarily eat flying insects, would help protect their crops and villages from potential predators and pests. When European settlers arrived, they also put up gourds and homemade nesting structures for the birds.

Historically, throughout most of the U.S., Purple Martins nested in natural tree hollows, old woodpecker holes, and cliff crevices near water. Out West, two subspecies continue to nest in natural cavities like hollow trees or even the arms of saguaro cacti. In the eastern US, however, habitat loss and competition with non-native species, such as English House Sparrows and European Starlings, have resulted in the Eastern subspecies nesting almost exclusively in man-made boxes. They are now dependent on these artificial structures for their survival.

With impressive dedication, some people from the Kent Land Trust and Marvelwood School have volunteered for decades to study and restore inland populations of martins. They organize and teach young people associated with various conservation organizations on how to manage housing for Purple Martins, enhancing their survival.

A binder with images of the birds at different ages is used to determine the age of the birds. The ones we banded were 11 to 22 days old.Tail and back feathers change daily, making dating them quite easy. While I was there, in addition to banding, the baby birds were counted and their ages were recorded. They usually fledge 26-32 days after hatching.

The Center tries to track the birds’ migrations to South America. It turns out that most go to Brazil. Some have radio transmitters attached, which track them whenever they pass a location with a signal. Some have a GPS device attached, which gives detailed migratory information if they are able to retrieve the device.

Purple Martins have experienced a significant population decline in recent decades, making monitoring crucial for identifying potential causes. Counting helps determine the impact of threats such as pesticide use, competition from other species, and changing weather patterns. By tracking population changes, researchers can evaluate the success of conservation strategies, such as providing artificial nesting structures and protecting wintering grounds.

There’s good news: increasing populations of martins in the northwest corner of Connecticut are beginning to pay dividends. An adult banded bird (from Miles Wildlife Sanctuary), along with another banded bird yet to be identified, was discovered by Jonathan Pierce to be breeding in an abandoned martin house near Stockbridge, MA. It is the first breeding record for Berkshire County since 1895!

It’s been fun to watch the activity in some bluebird nest boxes the Sharon Audubon Center installed on our property a few years ago. Since purple martins thrive around human activity, I’m now hoping they can also find a good spot nearby for a cluster of their homes.

The Audubon Center is a wonderful resource for learning about birds and nature. They and their collaborators are happy to teach us what we can do to help these beautiful creatures survive.

*All banding is conducted under a federally authorized Bird Banding Permit issued by the U.S. Geological Survey and state permits.

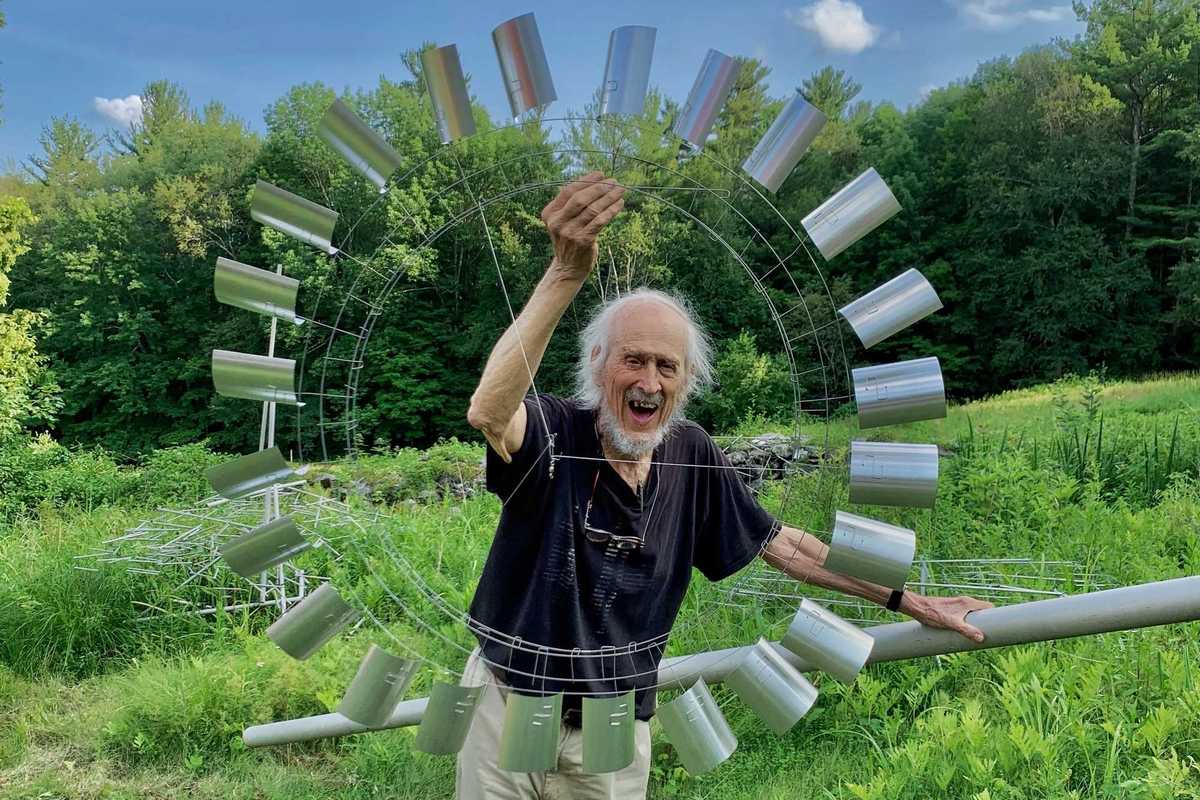

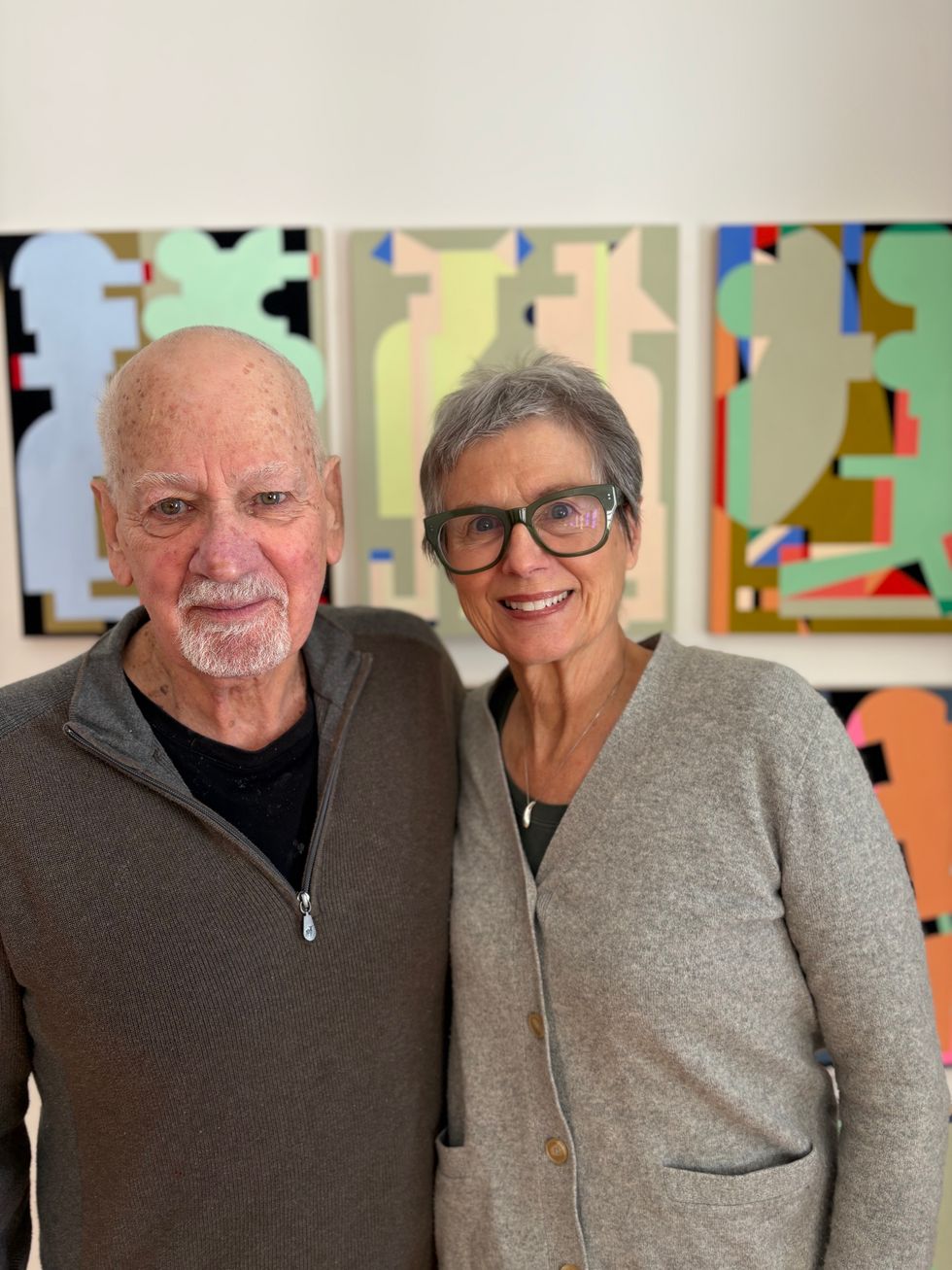

Plagens and Fendrich at home in front of some of Fendrich’s paintings. Natalia Zukerman

Plagens and Fendrich at home in front of some of Fendrich’s paintings. Natalia Zukerman

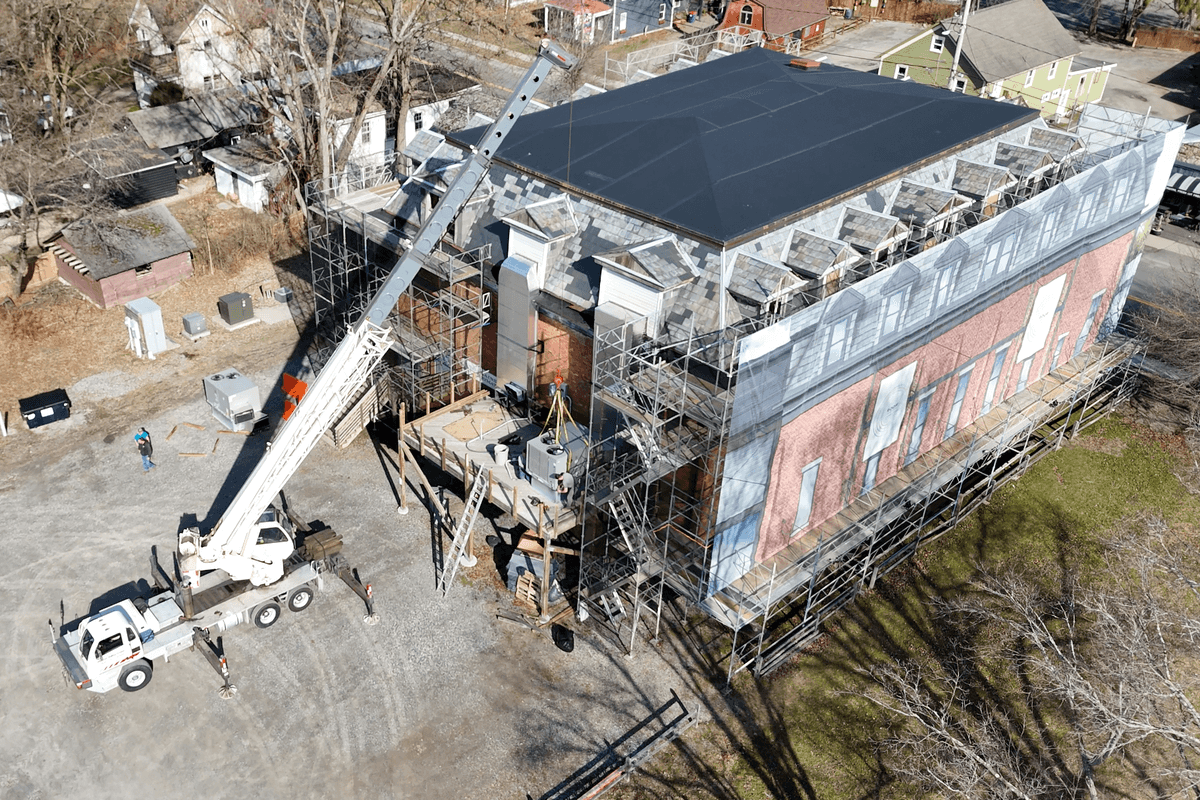

Interior of the Linde Center for Music and Learning.Hilary Scott, courtesy of the BSO

Interior of the Linde Center for Music and Learning.Hilary Scott, courtesy of the BSO

Bird banding at Sharon Audubon

Volunteers Laurie, Ashley, Hannah, Brendan, and Leah.