Advocates take action to protect birds from avian flu

Sunny Kellner, the wildlife rehabilitation manager at Sharon Audubon Center, said protective measures are in place to protect the center’s ambassador birds of prey, including Norabo, a turkey vulture, from potentially deadly avian influenza. Norabo, injured as a fallen chick, has been a resident at Sharon Audubon for about two years.

Debra A. Aleksinas

This white-headed duck at the Ripley Waterfowl Conservancy in Litchfield has an endangered conservation status. Ripley Waterfowl Conservancy

This white-headed duck at the Ripley Waterfowl Conservancy in Litchfield has an endangered conservation status. Ripley Waterfowl Conservancy

Kent's Ainsley Moffitt takes a shot against the Millbrook goalie.Photo by Lans Christensen

Kent's Ainsley Moffitt takes a shot against the Millbrook goalie.Photo by Lans Christensen Lily Kennedy on attack for Millbrook.Photo by Lans Christensen.

Lily Kennedy on attack for Millbrook.Photo by Lans Christensen. Ainsley Moffitt celebrates after scoring a goal for Kent.Photo by Lans Christensen

Ainsley Moffitt celebrates after scoring a goal for Kent.Photo by Lans Christensen

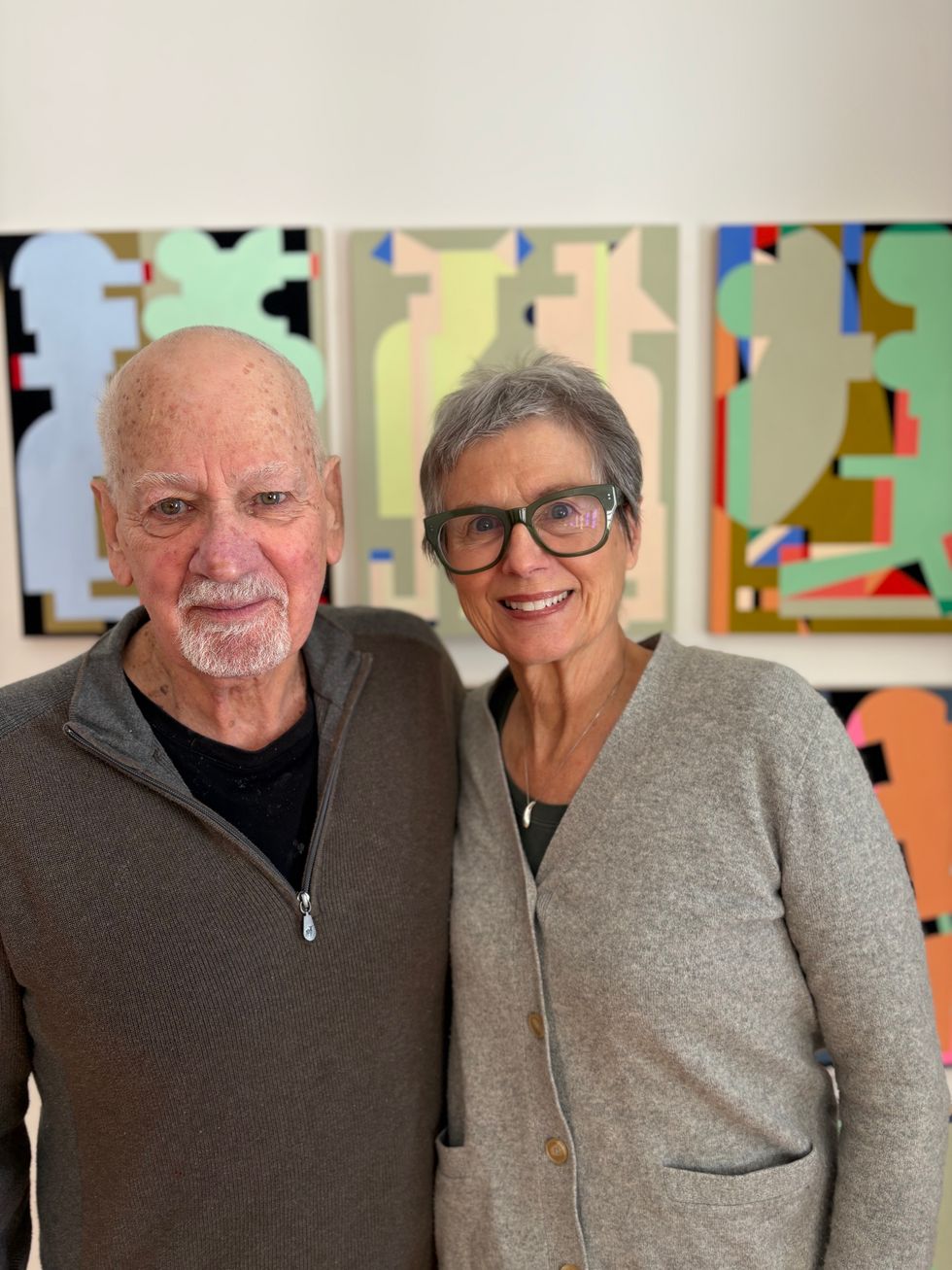

Plagens and Fendrich at home in front of some of Fendrich’s paintings. Natalia Zukerman

Plagens and Fendrich at home in front of some of Fendrich’s paintings. Natalia Zukerman