The greatest achievement of the Founders — their establishment of safeguards against the use of absolute power by a single individual or branch of government — is currently being erased.

When America’s Founders wrote the Constitution in 1787, the world had no democracies. Countries across the meridians were led by all-powerful kings and other dictators. An example was George III, the British monarch, who treated the American colonists as mere vassals who could be wantonly taxed despite their lack of representation, in whose homes British troops could be quartered at whim, and who constantly harassed colonial shipping in international waters — among other arbitrary activities backed by military force. This King, as is characteristic of dictators, eventually overplayed his hand and the thirteen colonies rose up in revolt.

The great genius of James Madison and his colleagues was to create the first true democracy in history, going far beyond the semi-democratic practices of ancient Greek cities and Swiss canons. They insisted on the sharing of power across three “departments” of government: the executive, legislative and judicial.

Their novel Constitutional endeavors had an overriding objective: to guard against the dangers of tyranny. Above all else, the Founders were imbued with anti-power values. No more autocratic leaders like King George.

The core philosophy guiding the Founders was to distribute power across three “branches” of government, as a means for limiting its potential abuse by any one branch. As Lord Acton would state in his famous aphorism a hundred years later, “Power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Long before Action, the colonists understood this principle. By establishing separate institutions — executive, legislative and judicial — “ambition would be made to counteract ambition,” as Madison stated the case in Federalist Paper 51. In this manner, no branch would grow so mighty as to dwarf the others or dictate to the American people.

Justice Louis Brandeis eloquently expressed the spirit of the Founders in a case that came before the Supreme Court in 1926 (Myers v. United States). “The doctrine of the separation of powers was adopted by the [Constitutional] Convention of 1787,” he wrote, “not to promote efficiency but to preclude the exercise of arbitrary power. The purpose was not to avoid friction, but by means of the inevitable friction incident to the distribution of governmental powers among three department, to save the people from autocracy” [emphasis added].

In contrast to this wise approach to governance, a more recent school of thought has embraced the concept of a “unitary” presidency. What becomes all-important in this approach is a powerful engine to move the nation forward — an unfettered president free to shape a nation’s destiny as the White House sees fit, without the interference of “checks-and-balances” from lawmakers on Capitol Hill or members of the Supreme Court. In this model, now in place in the United States, the legislative and judicial branches are largely supine to the will of the Oval Office and the president’s minions spread across the agencies of the executive branch.

The greatest achievement of the Founders — their establishment of safeguards against the use of absolute power by a single individual or branch of government — is currently being erased. It is a troubling time in the nation’s history, with liberty hanging in the balance. A starting place to restore our form of democratic restraints on arbitrary power is to support those members of Congress and the judiciary who understand the Constitution. Our fate depends heavily on America’s representatives and judges as independent guardrails in this struggle to continue our long and admirable history of shielding freedom against the forces of tyranny.

Loch K. Johnson taught political science for forty years at the University of Georgia, while also serving intermittently as a senior staff aide in the White House, the Senate, and the House of Representatives, and as a Fellow at Oxford and Yale Universities. He retired to Salisbury in 2019. Professor Johnson is the author of The Third Option: Covert Action and American Foreign Policy (Oxford University Press).

First Selectman Gordon Ridgway learns from 7th graders at Cornwall Consolidated School about the story of Robin Starr, a man who bought his freedom after serving in the Revolutionary War.Riley Klein

First Selectman Gordon Ridgway learns from 7th graders at Cornwall Consolidated School about the story of Robin Starr, a man who bought his freedom after serving in the Revolutionary War.Riley Klein

Fireworks over Satre Hill Friday, Feb. 6.Alec Linden

Fireworks over Satre Hill Friday, Feb. 6.Alec Linden

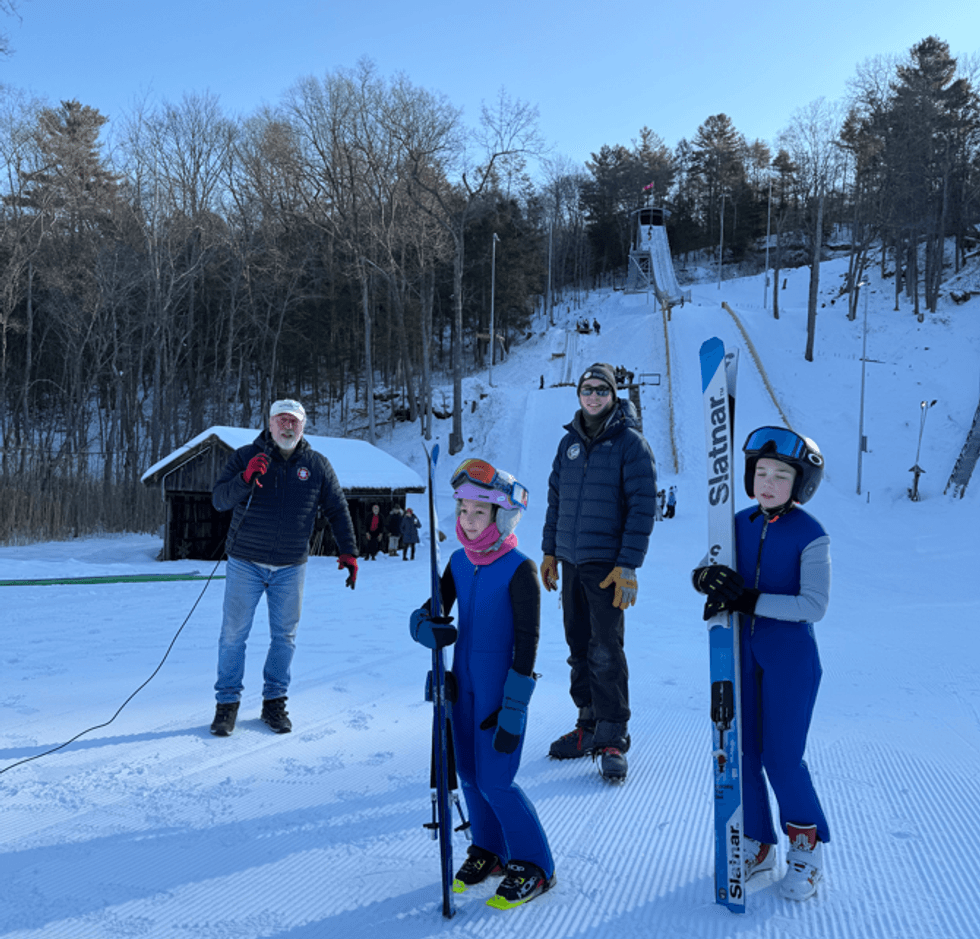

Salisbury Central School with SWSA jumpers.Dan Hubbard

Salisbury Central School with SWSA jumpers.Dan Hubbard  Willie Halloran of SWSA, Coach Seth Gardner, and ski jumpers Oona Mascavage and Camden Hubbard giving a history of Salisbury ski jumping and equipment demonstration.C Tripler

Willie Halloran of SWSA, Coach Seth Gardner, and ski jumpers Oona Mascavage and Camden Hubbard giving a history of Salisbury ski jumping and equipment demonstration.C Tripler The jumps at Satre Hill are groomed and ready for launch of the 100th annual Jumpfest Feb. 6 to 8.Photo by Lans Christensen

The jumps at Satre Hill are groomed and ready for launch of the 100th annual Jumpfest Feb. 6 to 8.Photo by Lans Christensen

Beware an unfettered presidency