Excessive Heat Watch. Heatwave Sparks Tornado. Crazy Connecticut Weather. Large Hail and Wind Damage. Fallen Trees Knock Out Power. Elevated Levels of Ozone.

Recent headlines bear out the reality: The climate crisis is here. Individuals can chip away at the problem by reducing their own emissions—driving EV’s, purchasing Energy Star appliances, flying less and eating more plant-based diets. Yet, in the absence of meaningful regulation at the federal level, coping with and adapting to the reality of what’s happening on the ground is left largely to loca and state governments. They are being forced to figure out how to manage their own risks and preparedness plans largely on their own.

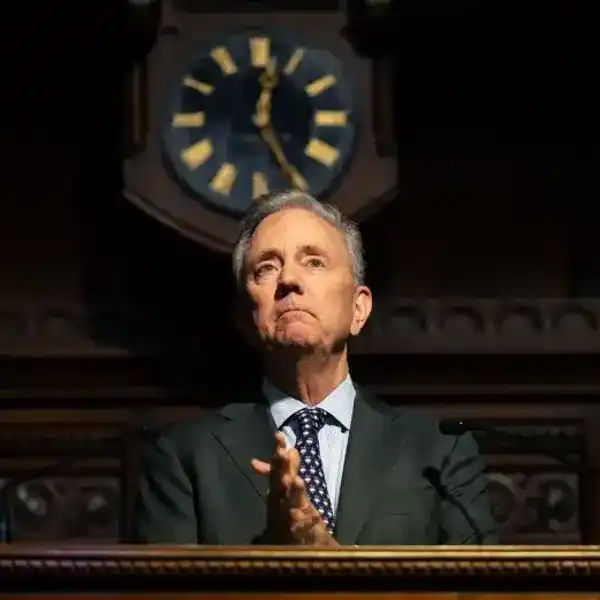

That’s why, when the State of Connecticut concluded its 2024 legislative session in May without passing two key bills to address climate change, State Representative Maria Horn (D-64) was, to say the least, chagrined.

One of the bills, HB5485, would have strengthened support for electric vehicles in the state by coordinating rebate programs and bolstering charging infrastructure. The other, HB5004, focused on improving the state’s resilience to climate change, providing incentives for businesses to adopt sustainable practices and accelerating the installation of hundreds of thousands of energy-efficient and cost-saving home heat pumps. Even with 71 co-sponsors and passage by the House of Representatives, the Connecticut Climate Protection Act never made it to the Senate floor for a vote.

In fact, this was the second year in a row that state leaders failed to pass key legislation to address climate change, leaving towns to face the climate crisis on their own. Meanwhile, in addition to being the hottest year on record, 2023 also witnessed the costliest weather and climate disasters.

“Whether you call it climate change or extreme weather, it’s hurting people. From a moral perspective, it’s our obligation to care for the world in which we live. From a health perspective, we need the environment to stay healthy. From a financial perspective, it is costing us money,” Horn stressed in a recent interview. Here she outlines additional observations and recommendations:

How is increased severe weather costing our towns money?

I’m hearing about infrastructure damage. Last July, flooding took out infrastructure in several towns. Dams that are under threat. We lost a couple of bridges in Norfolk, which cost about $5 million to repair. Gordon Ridgway, the First Selectmen in Cornwall, showed me an area where a riverbank became so saturated that if one tree were to come down, the entire bank and roadway would collapse. Last summer’s floods also washed out Cornwall’s dirt roads, blocked culverts and lifted an old rail freight line into the air.

Why don’t we simply switch to clean energy?

One of the claims we often hear is that we can’t afford to make the transition to green, renewable energy because it’s too costly. It’s true that because we don’t have the infrastructure in place to switch to renewables like wind and solar immediately, a transition would cost us in the short run. But it’s also true that Connecticut does have high energy costs now. So, we need to be cognizant of how a green energy transition would impact consumers and how we would protect those who are most vulnerable.

That said, doing nothing is not without cost. We are already experiencing significant healthcare costs due to transportation emissions that make asthma and other respiratory problems worse. And, as I explained, we have increased infrastructure costs. So even though these costs are all related to climate change, they’re dispersed. That’s why we have to do a better job of aggregating these climate change-related costs and clarify what climate change is actually costing us.

How dependent is Connecticut on fossil fuels for energy?

Interestingly, 40 percent of Connecticut’s power is generated by nuclear energy. And while that’s associated with other problems, it’s clean. However, it’s made us fall behind our neighboring states in adopting solar and wind energy alternatives.

What can local communities do to address our energy needs?

If we’re serious about green energy, we need to consider the big picture and figure out the right places to put energy infrastructure and transmission lines. We need to be more flexible. For example, we need solar arrays and wind turbines, even though they are not as scenic as people might like. We need some large ones, and we need to make sure that we site them in the right places.

We need to listen to one another and realistically consider our options. A lot of communities are looking at installing solar fields on their school rooftops or near their transfer stations. States and communities need a process for making these decisions.

Since the recently proposed bills failed to pass, what can towns in Connecticut’s Northwest Corner due to pave the way for climate change legislation?

They can do an infrastructure audit. We did pass some legislation that will help towns pay for the repair of dams and other infrastructure affected by extreme weather. In the meantime, towns need to better understand where they’re exposed to risks so they can continue to build support and make the case for those additional costs.

Communications consultant Carol Goodstein has written extensively about climate change, biodiversity loss, deforestation and related topics and for many years was director of communications and marketing at the Rainforest Alliance. She lives in Norfolk.

A talk with Maria Horn

…on the cost of a changing climate

Route 272 in Norfolk was breached by heavy rains that started on Sunday, July 10, 2023, prompting an emergency declaration.