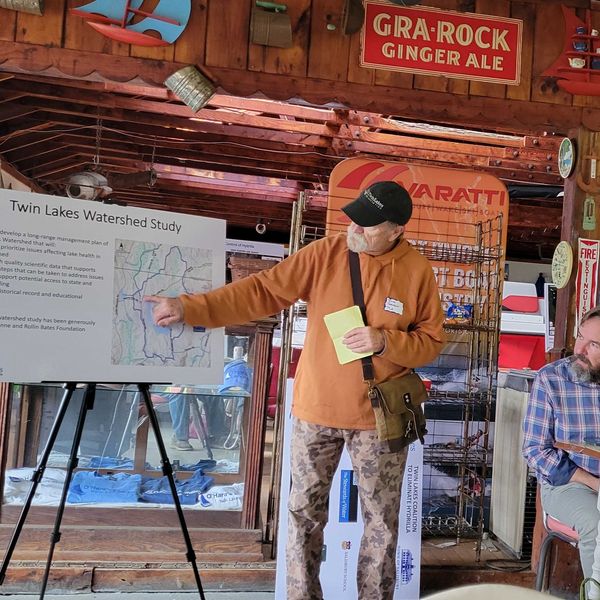

Gregory Bugbee, associate scientist at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station (CAES), where he heads the Office of Aquatic Invasive Species (OAIS), was a guest speaker at the Aug. 2 annual meeting of the Twin Lakes Association.

Debra A. Aleksinas

lakevillejournal.com

lakevillejournal.com

Visitors consider Norman Rockwell’s paintings on Civil Rights for Look Magazine, “New Kids in the Neighborhood” (1967) and “The Problem We All Live With” (1963.) L. Tomaino

Visitors consider Norman Rockwell’s paintings on Civil Rights for Look Magazine, “New Kids in the Neighborhood” (1967) and “The Problem We All Live With” (1963.) L. Tomaino

Styling a tray can give a home or room a re-fresh.Kerri-Lee Mayland

Styling a tray can give a home or room a re-fresh.Kerri-Lee Mayland