Latest News

Classifieds - February 26, 2026

Lakeville Journal

Feb 25, 2026

Help Wanted

PART-TIME CARE-GIVER NEEDED: possibly LIVE-IN. Bright private STUDIO on 10 acres. Queen Bed, En-Suite Bathroom, Kitchenette & Garage. SHARON 407-620-7777.

The Salisbury Association’s Land Trust seeks part-time Land Steward: Responsibilities include monitoring easements and preserves, filing monitoring reports, documenting and reporting violations or encroachments, and recruiting and supervising volunteer monitors. The Steward will also execute preserve and trail stewardship according to Management Plans and manage contractor activity. Up to 10 hours per week, compensation commensurate with experience. Further details and requirements are available on request. To apply: Send cover letter, resume, and references to info@salisburyassociation.org. The Salisbury Association is an equal opportunity employer.

Gardeners needed for native plant design business: March 15-December 1st. Must be physically fit and dependable. Call for interview 347-496-5168. Resume and references needed.

Weatogue Stables in Salisbury, CT: has an opening for experienced barn help for Mondays and Tuesdays. More hours available if desired. Reliable and experienced please! All daily aspects of farm care- feeding, grooming, turnout/in, stall/barn/pasture cleaning. Possible housing available for a full-time applicant. Lovely facility, great staff and horses! Contact Bobbi at 860-307-8531. Text best for prompt reply.

Services Offered

Hector Pacay Landscaping and Construction LLC: Fully insured. Renovation, decking, painting; interior exterior, mowing lawn, garden, stone wall, patio, tree work, clean gutters, mowing fields. 845-636-3212.

PROFESSIONAL HOUSEKEEPING & HOUSE SITTING: Experienced, dependable, and respectful of your home. Excellent references. Reasonable prices. Flexible scheduling available. Residential/ commercial. Call/Text: 860-318-5385. Ana Mazo.

Pets

12 week old black and tan/blue tick coonhound: mix for sale. First set of puppy shots done at 8 weeks. Call 860-248-9947 for more info. and price.

Real Estate

PUBLISHER’S NOTICE: Equal Housing Opportunity. All real estate advertised in this newspaper is subject to the Federal Fair Housing Act of 1966 revised March 12, 1989 which makes it illegal to advertise any preference, limitation, or discrimination based on race, color religion, sex, handicap or familial status or national origin or intention to make any such preference, limitation or discrimination. All residential property advertised in the State of Connecticut General Statutes 46a-64c which prohibit the making, printing or publishing or causing to be made, printed or published any notice, statement or advertisement with respect to the sale or:rental of a dwelling that indicates any preference, limitation or discrimination based on race, creed, color, national origin, ancestry, sex, marital status, age, lawful source of income, familial status, physical or mental disability or an intention to make any such preference, limitation or discrimination.

Real Estate For Sale

FOR SALE: 39 Hospital Hill Road, Sharon. 1680 sq.ft. Two family, rare side-by-side units. 4 bed; 2 full bath, 2 half. Great investment, or live in one and rent other side. $485,000. Call/text Sava, 914 -227-4127.

Business Opportunities

FOR RENT COMMERCIAL KITCHEN IN FALLS VILLAGE: Located in the heart of Falls Village. 425 sf space fully equipped for catering business, wholesale food prep or bakery. Several successful local businesses got their start here! Event space in building could be available. Contact anita@100mainst.com.

Keep ReadingShow less

To save birds, plant for caterpillars

Dee Salomon

Feb 25, 2026

Fireweed attracts the fabulous hummingbird sphinx moth.

Photo provided by Wild Seed Project

You must figure that, as rough as the cold weather has been for us, it’s worse for wildlife. Here, by the banks of the Housatonic, flocks of dark-eyed juncos, song sparrows, tufted titmice and black-capped chickadees have taken up residence in the boxwood — presumably because of its proximity to the breakfast bar. I no longer have a bird feeder after bears destroyed two versions and simply throw chili-flavored birdseed onto the snow twice a day. The tiny creatures from the boxwood are joined by blue jays, cardinals and a solitary flicker.

These birds will soon enough be nesting, and their babies will require a nonstop diet of caterpillars. This source of soft-bodied protein makes up more than 90 percent of native bird chicks’ diets, with each clutch consuming between 6,000 and 9,000 caterpillars before they fledge. That means we need a lot of caterpillars if we want our bird population to survive.

So how do we ensure that there are sufficient caterpillars for them? That is the question, as caterpillars are very particular. Their butterfly or moth mothers cleverly attach their eggs to the very specific plants their tiny babies require. Once they hatch, the caterpillars eat the leaves of these plants until they are either picked off by birds to feed their young or create a chrysalis and turn into a moth or butterfly to repeat the cycle of life.

Some caterpillars are generalists and can survive on a variety of plants, but most — 90 percent, according to scientists — are specialists, relying on only one or two types of plants for survival. In their winged form, dietary restrictions ease as they source pollen more widely, but when it comes time to lay eggs, they use a keen sense of smell to find the specific plants that will help their young survive.

Research by Doug Tallamy shows that 90 percent of butterfly and moth species rely on just 14 percent of native plant species for food, which makes the planting of these “keystone” plants critical. Let’s review a few.

Goldenrod: Not all goldenrod is created equal. Old field goldenrod, (Solidago nemoralis), is a shorter and less aggressive alternative to the tall, aggressive goldenrod we are familiar with, as is wrinkleleaf goldenrod, (Solidago rugosa), a compact species that has arching sprays of bright yellow flowers supporting more than 100 species of insects. This species is deer-resistant with no serious pests or diseases. Last year, Mt. Cuba Center, a conservation center out of Delaware, focused its trials on goldenrod, and its research report, available online, is sortable not just by aesthetic attributes but also by the number of insects seen on each species.

Scarlet strawberry: (Fragaria virginiana), is one of the plants I have had great luck growing in the woodland. When there is a new sunny spot, which happens when a tree or large branch falls, I plant a few strawberries, which I dig out of a spot where they are thriving. These plants make a great groundcover and are especially nice used under trees for caterpillar “soft landings.”

Spotted Joe-Pye weed: We see this plant, (Eutrochium maculatum), on roadsides in late summer, but it looks as sharp as an ornamental in the hands of Michael Trapp, who, in the garden behind his shop in West Cornwall, encloses a bed of Joe-Pye weed with a short boxwood hedge, dignifying this plant that supports between 35 to 40 caterpillar species, including those that become the three-lined flower moth, Clymene moth, ruby tiger moth, Eupatorium borer moth and great spangled fritillary moth.

I am less familiar with fireweed, (Chamaenerion angustifolium), but will be adding it this year, as it may be the prettiest of the keystone plants in our region and attracts the fabulous hummingbird sphinx moth. I will let you know when I find a local nursery that stocks it and, when planted, how it fares here.

Also keep in mind this spring: smooth aster, (Symphyotrichum laeve); white yarrow, (Achillea millefolium); and the beautiful Canadian columbine, (Aquilegia canadensis), which is the first food for hummingbirds’ arrival in the Northwest Corner.

Dee Salomon ‘ungardens’ in Litchfield County.

Keep ReadingShow less

Stephanie Haboush Plunkett and the home for American illustration

Robin Roraback

Feb 25, 2026

Stephanie Haboush Plunkett

L. Tomaino

"The field of illustration is very close to my heart"

— Stephanie Plunkett

For more than three decades, Stephanie Haboush Plunkett has worked to elevate illustration as a serious art form. As chief curator and Rockwell Center director at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, she has helped bring national and international attention to an art form long dismissed as merely commercial.

Her commitment to illustration is deeply personal. Plunkett grew up watching her father, Joseph Haboush, an illustrator and graphic designer, work late into the night in his home studio creating art and hand-lettered logos for package designs, toys and licensed-character products for the Walt Disney Co. and other clients.

“The field of illustration is very close to my heart,” she said. Inspired by that example, she studied illustration at Pratt Institute and began her career as an illustrator before shifting toward museum work. An internship at the Brooklyn Museum proved pivotal. “It was inspiring to see the children come alive in front of art,” she recalled.

In addition to her curatorial work, Plunkett is the author of two children’s books, “Kongi and Potgi: A Cinderella Story from China” and “Sir Whong and the Golden Pig,” and has written or co-authored numerous books on illustration, including “Drawing Lessons from the Famous Artists School” and “Leo Lionni: Storyteller, Illustrator, Designer.” She earned an MFA from the School of Visual Arts and built a museum career that included positions at the Brooklyn Museum, the Brooklyn Children’s Museum and the Heckscher Museum of Art before joining the Norman Rockwell Museum, where she has worked for 31 years.

But elevating illustration has meant challenging decades of critical skepticism.

“The goal has been to shine a light on this important American art form and to elevate public awareness of its artistic and cultural importance,”Plunkett said.

As a popular and widely circulated art, illustration is sometimes thought of as inferior to fine art, such as painting and sculpture. Plunkett considered why. She theorized that the 1913 New York Armory Show, the International Exhibition of Modern Art, with works by artists such as Picasso, Matisse and Duchamp, initially contributed to this evaluation. In the 1930s and ’40s, abstract expressionism became the art of the nation, and the rift widened further.

“Norman Rockwell became the antihero for many art critics of the time,” said Plunkett. “Illustration was viewed as too commercial and sentimental because of its emphasis on visual storytelling.”

Plunkett calls illustration “art with a job to do.” She explained, “Illustrators are adept at solving visual problems for their clients while expressing their own aesthetic and artistic vision.”

She noted that the line between the fine and applied arts “is much more porous now, with many artists working across platforms and styles.” She cited late-20th-century illustrators like Marshall Arisman, Barbara Nessim, Robert Cunningham, Bernie Fuchs and Mark English as illustrators who forged unique approaches to working and seeing.

Plunkett commented that people want to see the original illustrations. “Generally, Rockwell exhibitions bring high attendance. Currently, our traveling exhibition, ‘Norman Rockwell: From Camera to Canvas,’ is at the New Britain Museum of American Art, but we’ve traveled Rockwell and illustration to 45 states and several countries, including Japan, France, Italy and Germany.”

Nowadays, illustrators take on subjects that are important to them. “The children’s book industry is committed to sharing the richness and diversity of people and cultures with young readers.” Plunkett cited the late illustrator Jerry Pinkney’s commitment to this goal. As a boy, Pinkney found no books portraying children like him, and “his life’s mission as an artist was to present inspiring, positive images of children of color.”

The Norman Rockwell Museum and Rockwell Center seeds were sown when “Rockwell placed the first 199 artworks in the care and collection of the Norman Rockwell Museum upon its founding in 1969, some of which he personally acquired for the fledgling collection,” said Plunkett. “The museum’s current Rockwell holdings include 865 original artworks, the artist’s Stockbridge studio and an archive of 400,000 photographs, letters, props and first uses of the artist’s work. We also hold about 25,000 illustrations by other artists, from the historical to the contemporary.”

“We call ourselves the home for American illustration. We have a real commitment to illustrators and what they’ve accomplished,” said Plunkett.

The Norman Rockwell Museum is located at 9 Glendale Road, Stockbridge. For more information and to purchase tickets, visit

nrm.org

Keep ReadingShow less

Want more of our stories on Google? Click here to make us a Preferred Source.

The power of one tray

Kerri-Lee Mayland

Feb 25, 2026

A tray can help group items in a way that looks and feels thoughtful and intentional.

Kerri-Lee Mayland

Winter is a season that invites us to notice our surroundings more closely and crave small, comforting changes rather than big projects.

That’s often when clients ask what they can do to make their homes feel finished or fresh again — without redecorating, renovating or shopping endlessly. My answer: start with one tray.

A tray creates a moment. It gives the eye a place to land and turns everyday objects into something intentional. More importantly, it’s approachable. There’s no measuring, no commitment, no pressure to get it “right.” It’s a small, easy project — affordable, functional and even a little fun — that can be tailored entirely to you.

One of the things I love most about styling trays is that your cozy “moment” becomes mobile. Everything you love is gathered in one place and can be easily moved from room to room as your day unfolds. A tray that starts on an entry table can later migrate to a coffee table or kitchen counter, adapting to how you’re actually living in your home.

In one client’s entryway, we styled a tray that sets the tone the moment you walk in. A simple pair of brass candlesticks adds warmth, a blue-and-white chinoiserie vase brings character, and two vintage books ground the arrangement. It’s not decorative for decoration’s sake — it feels collected, welcoming and personal, all while keeping the surface from becoming cluttered.

In another home, a coffee table tray became the quiet anchor of the living room. We included a strand of wooden beads for texture, the TV remote tucked neatly into a small vintage box, and a plant nestled in a pottery bowl. The tray keeps everyday necessities close at hand while making the space feel relaxed and lived-in rather than chaotic.

Kitchens may be where trays work hardest, especially in winter when we’re cooking inside more and gathering more casually. For one client, we styled a tray with a pepper mill; a shallow bowl for garlic, shallots and onions; and a white Italian ceramic container filled with olive oil. It’s practical and beautiful, and it makes cooking feel intentional instead of rushed. The tray warms up the counter while keeping essentials within reach.

Another version I often create is the cocktail, mocktail or tea-and-coffee tray — endlessly useful for friends popping over to say hello. A few cups, a teapot or carafe, honey or sugar, and a candle create an inviting setup that’s ready at a moment’s notice. It says, “Stay a while,” without any fuss.

What makes trays so effective this time of year is that they respond to winter’s quieter rhythm. Winter decorating isn’t about bold color or dramatic statements — it’s about texture, warmth and restraint: wood, stone, ceramic, linen, candlelight. A tray helps you edit rather than add, grouping items so they feel thoughtful instead of scattered.

When the seasons shift, the same tray evolves with you. Heavier elements can be swapped for lighter ones — fresh flowers, glass, pale ceramics — without starting over. One tray, styled seasonally, becomes a constant that gently changes rather than something that has to be replaced.

Remember, good design doesn’t have to come from big gestures. Often it comes from small moments done well — a surface that feels intentional, a corner that feels cared for. In winter’s stillness, creating a simple tray may be just enough to make your home feel calm, personal and complete.

Keep ReadingShow less

Tangled specks: tiny flies, big ambitions

Patrick L. Sullivan

Feb 25, 2026

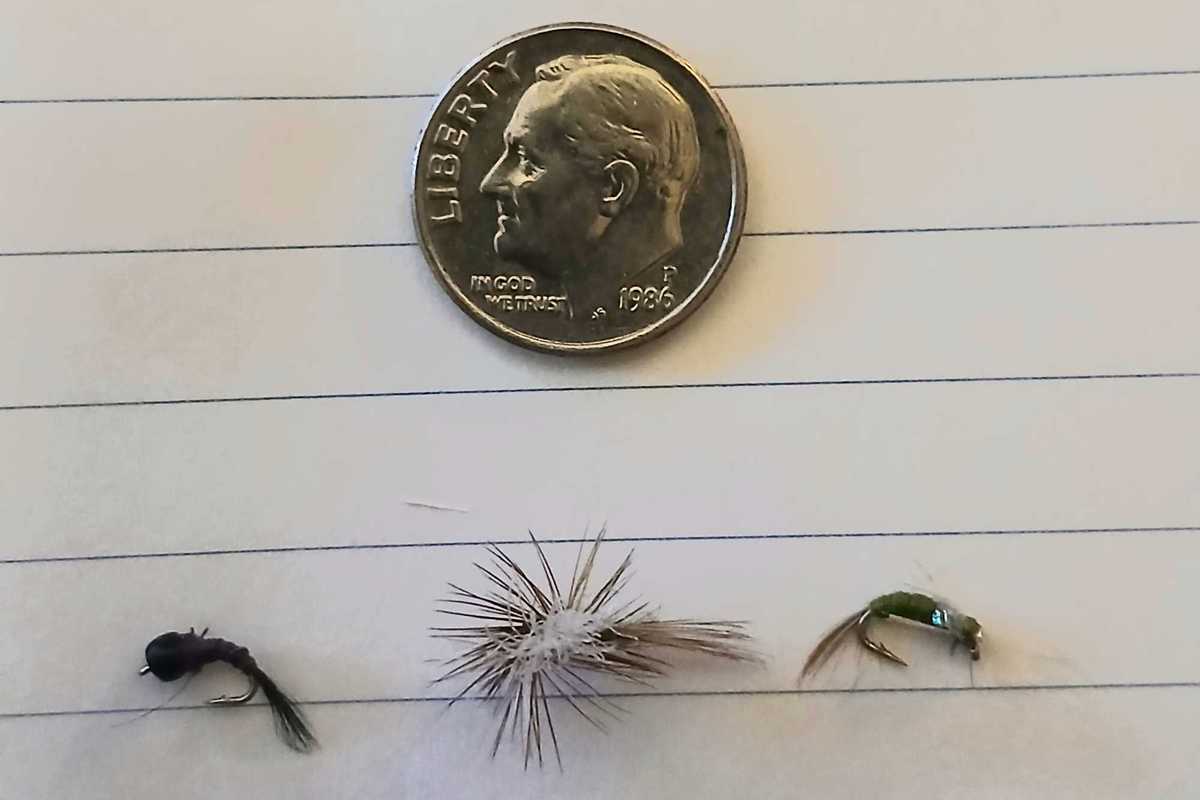

Here is a sample from a recently purchased assortment of specks. From left: Black speck, Parachute Adams dry fly speck, greenish sparkly speck.

Patrick L. Sullivan

I need to get my glasses checked

My fingers fumbling like heck

I have become a nervous wreck

Must be the season of the speck…

(With copious apologies to Donovan).

I’m still on the injured reserve list following replacement right hip surgery. Right now the plan is to come off the IR June 1, but I’m going to ask if we can’t shave something off that.

And yes, the rehab is going very well, thank you for asking.

What this means in practical terms is I am scheming and plotting like nobody’s business about all the fishly things I am going to do once Ye Doctor blows the all-clear.

I have glaring weaknesses in my angling game. I stink at roll casting. I’m hopeless with 12-foot leaders.

And I am really lousy at fishing with the kind of tiny little flies I refer to as “specks.”

I define a speck as anything smaller than size 20. Speck experts will disagree, as they think a size 20 is huge. Maybe I will think so too some day.

One of the perils of sitting around after surgery is scrolling through social media and buying things. For preference, things I don’t need.

I got some weird t-shirts. One sports the logo of the Shenandoah (Pa.) Hungarian Rioters, a 19th century minor league baseball team. Another reads “Surely Not Everyone Was Kung Fu Fighting.”

Among these idiotic acquisitions was an offer of 72 specks for about $50. This was a rock-bottom price, and it wasn’t coming from a fly-by-night outfit either, but from an online company, The Catch and the Hatch, who provided me with some very good perdigon nymphs a few years back.

So the specks arrived, and they are everything I feared.

Tiny. Hard to see. Did I say tiny? Infinitesimal. You know.

SPECKS!

Here’s why an angler needs to know how to use specks. In between the nice hatches of large, easily identifiable bugs, which is most of the time, trout eat little bugs.

If it’s a cloudy day, chances are there will be blue-wing olives on the water. Then there is a category called midges which contains multitudes.

I look at the river for five minutes, see nothing happening bug-wise, and I start trying to provoke a reaction somehow.

What I am missing is the trout happily eating specks beneath the surface.

So how am I going to do this?

What little speck success I’ve had has been with a dry-dropper rig. I use a big Stimulator or Chubby Chernobyl, a large, very visible, very buoyant dry fly, and tie a piece of fluorocarbon tippet to the bend of the dry fly’s hook with an improved clinch knot and attach the speck to that. A bass or panfish popper works as the dry fly too.

Here’s the problem. The speck hook eyes require a very fine tippet material — 6x, 7x, even 8x.

I dislike fine tippets even more than specks. The stuff is devilish. It curls up. It refuses to knot. It’s just awful to work with.

Some years back I discovered one brand of fluoro tippet with a 5x tippet that was somehow able to get through the eye of a size 22 hook. That made a difference.

But this moderately successful method is very one-dimensional. I need to be able to construct a leader with a dropper or two and get my specks down in the water column.

That’s going to mean 6x or worse, probably. I might have to add some weight, another thing I dislike and am not good at.

But that is the plan. I hope to report great things as I master the speck this season.

Or until my left hip goes out.

Keep ReadingShow less

Suzan Scott sees every detail in ‘This Beautiful Place’

Patrick L. Sullivan

Feb 25, 2026

Torrington artist Suzan Scott talked with visitors at a reception for her show “A Beautiful Place” at the David M. Hunt Library Saturday, Feb. 21.

Patrick L. Sullivan

Landscape painter Suzan Scott said, “I see every leaf on every tree, every blade of grass,” when she assesses a particular view. Her paintings are her effort to “distill it to the essence.”

Scott said she has been painting for 30 years, and she moved from central Connecticut to Torrington a few years ago to be closer to the landscapes she prefers. “I just get in the car and drive.”

One painting, with dramatic clouds and light, was the result of a group project. The leader suggested a protest theme, and Scott was not initially enthused. But that was the summer of 2023, when smoke from wildfires in Canada drifted into the Northeast U.S. The phenomenon yielded spectacular sunsets, among other things. So Scott was able to comment on the situation in a subtle manner without taking an overtly political stand.

Scott’s paintings are on display at the David M. Hunt Library in Falls Village through Friday, March 13. She will give a talk at the library on Thursday, March 12, at 5:30 p.m.

Keep ReadingShow less

Want more of our stories on Google? Click here to make us a Preferred Source.

loading